There is an undeniable influx of war-based exhibitions on show throughout Australia as we mark the centenary of World War I, ironically deemed ‘‘the war to end all wars’’. Sanctuary: Tombs of the Outcasts is unique in its approach, asking audiences to reflect upon this notion in light of 100 years of conflict since the Great War.

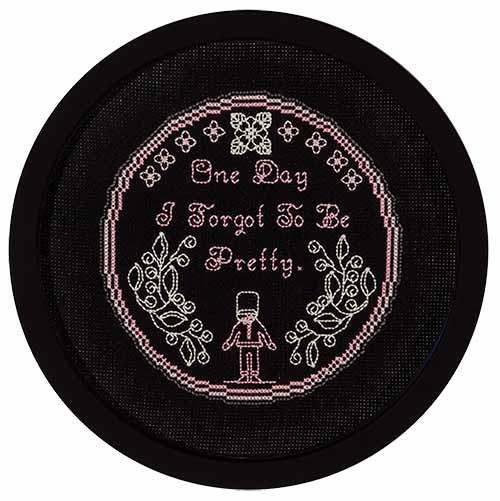

Sombre narratives of mateship and sacrifice underpin many WWI centenary commemorations. Brook Andrew seeks to challenge the dominant narrative of war conventionally communicated by institutions by exposing the often edited and exclusionary nature of commemorative displays. He endeavors to provide a voice to the ‘‘outcasts’’; those who have been excluded from the prevailing narrative of war in Australia. The resulting exhibition is a memorial which itself questions the act of commemoration, examining the notion of collective memory, the formation of national identity and, pointedly, who is excluded from this narrative.

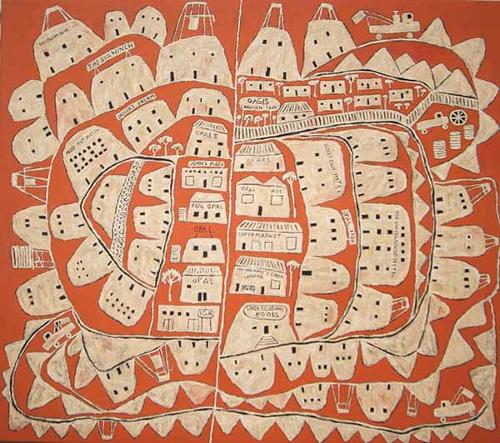

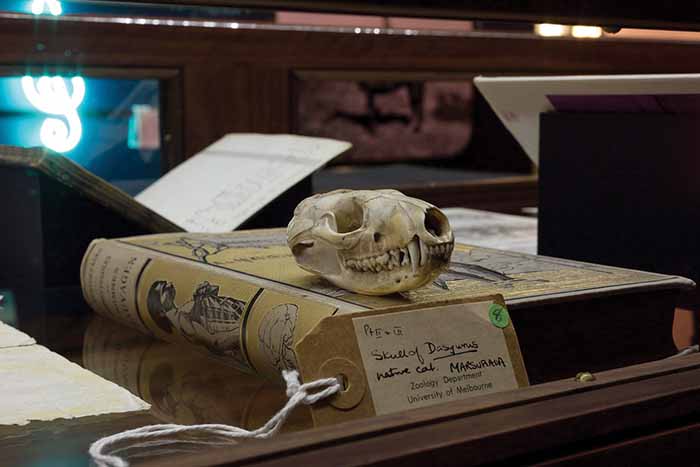

Sanctuary: Tombs of the Outcasts comprises a series of dark, at times confined, tomb-like spaces housing a myriad of objects and images sourced from both the University of Melbourne collections and Andrew’s personal collection. A plethora of images of Australian soldiers are interspersed with portraits of Indigenous men, while The Newsletter of Australasia – ‘‘a narrative to send to friends’’ – is juxtaposed with a register accounting for an estate’s increase and decrease in slaves.

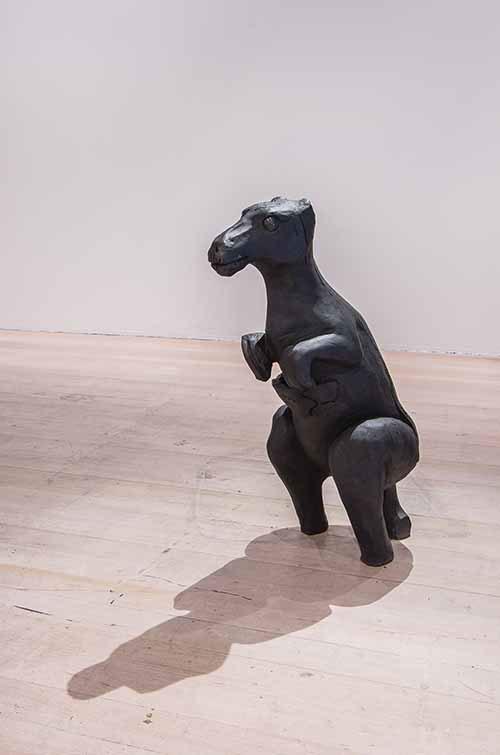

A formal letter marked ‘‘Application: Non-Aryan, ex-employee and other’’ appeals for the release of a German employee from an internment camp to resume work at Shell, Melbourne, while a print reminds us that ‘‘Legions of War Widows Face Dire Need in Iraq’’. LPs of South Pacific music sit alongside a newspaper headlined ‘‘Decoy and secrecy on Nauru abuse’’ while images of fighting gladiators, wounded soldiers and army funerals provide a marked contrast to a Gucci advertisement displaying the latest in military-style fashion. Concluding this eclectic assortment of images and objects, a solitary glass casket-like sculptural work provides a contemplative, metaphoric memorial to the unacknowledged ‘‘outcasts’’.

There do seem to be too many tangents to fluently merge, but this in itself reflects the depth and complexity of our history of conflict and immigration, which cannot be conveyed simply and eloquently through the likes of ANZAC legends. Sanctuary: Tombs of the Outcasts highlights the rich but contradictory nature of our diverse history; almost haphazardly merging themes of war and diaspora, immigration and sanctuary, globalisation, popular culture and inequality.

Though curator Vincent Alessi asserts that the exhibition does not aim to be overtly political, it is inevitably a stronger provocation than many other centenary exhibitions. It does not deny the ANZAC legend, rather repositions it as one of a plethora of unacknowledged stories. Andrew does not come across as accusatory or critical, rather he provides a quiet commentary that raises more questions than it answers. Sanctuary: Tombs of the outcasts gently and at times poetically acknowledges the complexities of representing and memorialising human suffering, a poignant articulation among an abundance of exhibitions commemorating the ANZAC centenary.