How far back do we go to examine how Australians see themselves? The facts of our nation’s founding are terrible and remain so. Who we are is filtered through a range of issues and factors and is, if we acknowledge the culture wars of the last few decades, a subject of divisive debate. Curator Wes Hill is probably not hoping to solve anything with the decisions made in the construction and content of Outside Thoughts, but there is something significant being discussed, and this is an issue of perspective.

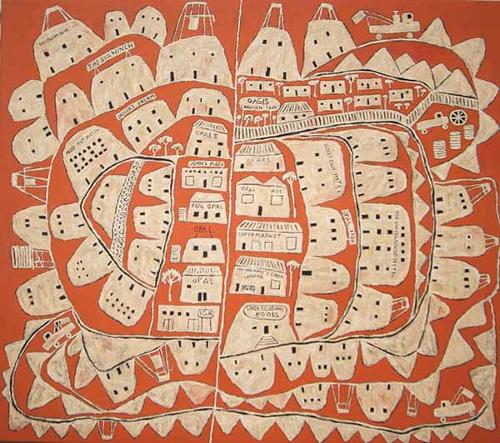

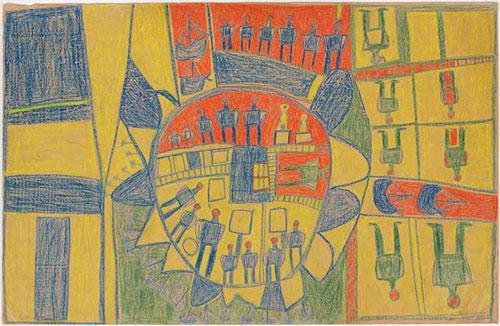

The perspective granted seems aerial at first. Mitch Cairn’s peculiar oil painting Gull (2015), its odd formal appearance almost robotic, stares over a wide expanse with the multiple objects of Emily Floyd’s Night Of The Octopus (2013) firmly claiming the centre as Danie Mellor’s print on aluminium The Spectre and Shadow (bayi wungumali) (2014) faces off with Darren Sylvester’s lightjet prints evoking the beach.

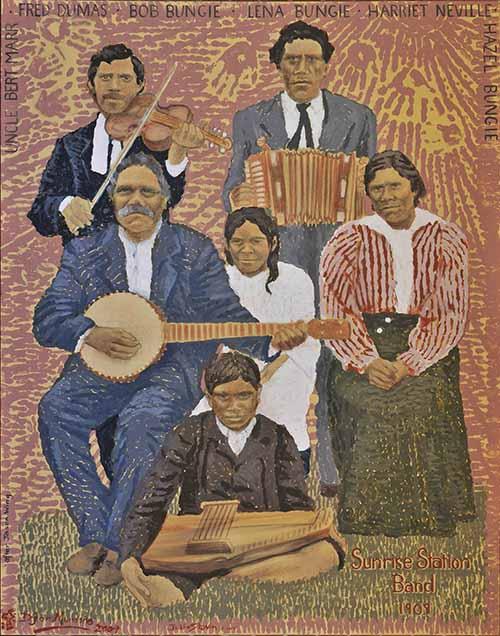

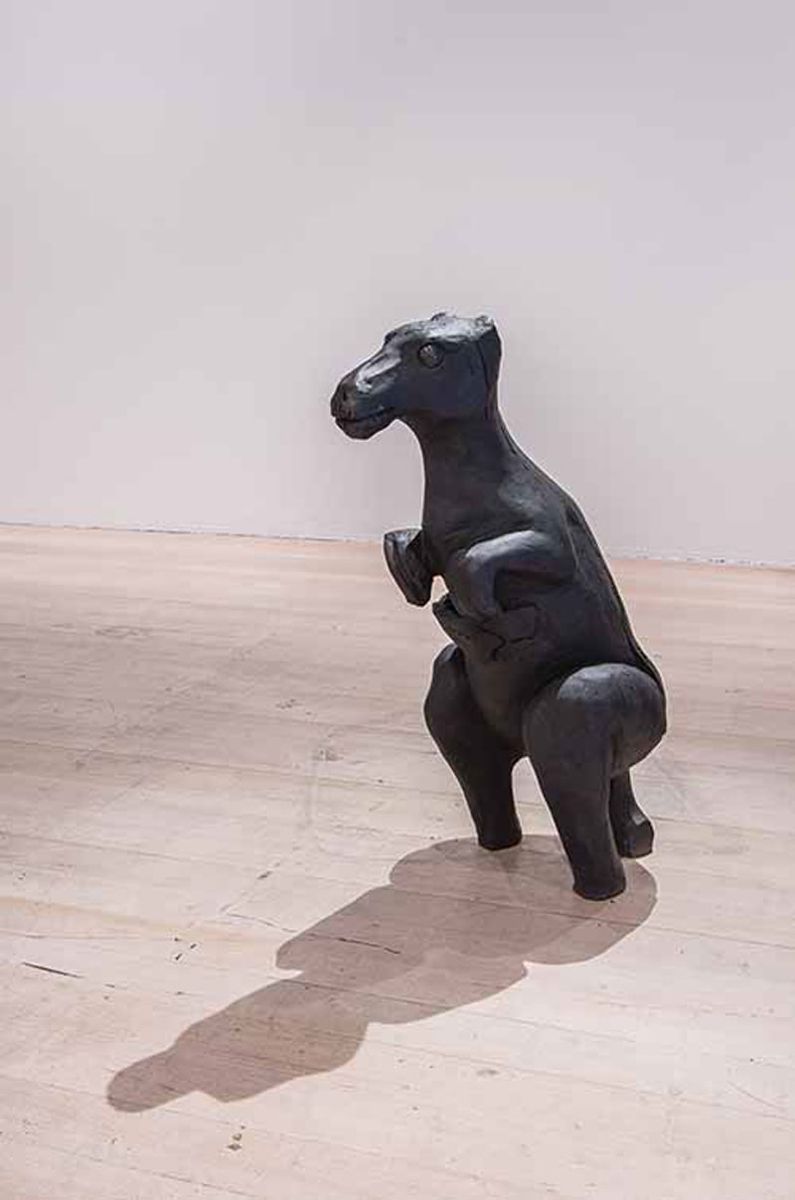

At the end of the gallery, almost out of the action, sits a mournful, cracked, bronze wallaby, which was probably never a wallaby at all but an approximation of one. This creature is actually Danie Mellor’s work and this revelation of uncertainty and incompleteness opens the show up; we are outside, looking in at something that appears beautiful, but has something malignant crawling through it. In Sylvester’s photographs the beach isn’t real and the people populating this artificial space appear hypnotised; while on the opposing wall in Mellor’s print the juxtaposition of a stylised image of Aboriginal people and a floating skull serve to remind us of the atrocities that have occurred since European settlement.

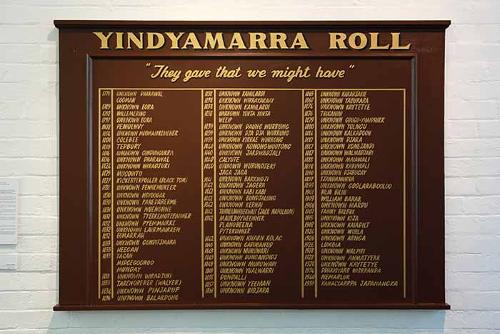

The gallery is a symbolic map made of viewpoints, notions of identity from a crackling psychic landscape. There is a nod in this construction to the traditions of landscape painting that have existed in Australia, from the feel of being overwhelmed by the alien potency of the country (resulting, perhaps in a desire to remake the land, which a lot of early colonial artists did), to the notion that the land was empty. Still, that is the colonial way: if you tear it down and burn it to the ground you can say it was never there, and we can all go to the beach and stare at the sun until we go blind, although it appears we were anyway.

Are we asleep with our eyes open? Do we cover up reality with glittering artificiality and the celebration of the body? Are we trying to ignore a wounded land and its wronged first people?

Overall, there is a feeling of unease here. None of these works are about security, but instead speak of alienation and denial. The idea that these are aspects of what makes up the Australian national psyche is hard to refute. They are not the full story, of course, but you’d need a lot more space and time to explore that, because the reality is that this show is not, as it first appears, a map, but a compass, pointing towards a heart of darkness.