The curatorial premise for Massimiliano Gioni's 55th Venice Biennale is by equal measures brilliant, romantic and just a little bit smug, with its clever and pointed self-awareness of its own limitations.

The Encyclopedic Palace (2013) takes its title from the imaginary museum patented by Italian-American artist Marino Auriti in 1955. Envisioned for downtown Washington D.C., this behemoth 136-storey, 16-block building was designed to house all worldly knowledge. Funnily enough the idea didn’t evolve beyond the model built in Auriti’s Pennsylvanian garage, but for Gioni it’s an idea that necessarily gives permission for absolutely anything to be included and for those inclusions to be forgiven.

In placing Auriti’s totemic model in the opening hall of the Arsenale, Gioni makes explicit the parallels between the romantic folly of Auriti’s vision and the inevitably fraught task of trying to present a singular look at current contemporary art practice. Never mind trying to do this within the context of an international biennale saddled with a formal architectural framework dictated by historical, imperialist politics. (Something Germany also acknowledged this year by swapping pavilions with the French and asking Ai Wei Wei to represent them.)

But you can largely forgive Gioni the perfect convenience of his premise because there’s a lot to like and some well-articulated ideas that really resonate visually. Taking an anthropological approach to exploring the role of imagination in the artistic process, and the way images have been used throughout history to classify knowledge, works like Steve McQueen’s Once Upon A Time (2002), demonstrate a succinct intelligence. Projecting 116 digitised images of the photographs that NASA launched into space in 1977 to depict life on earth to an extra-terrestrial gaze, here McQueen replaces the soundtrack of world music and rainstorms with linguist William J. Samarin’s field recordings of people speaking in tongues. It could be an apt metaphor for the biennale viewing experience. The same could be said for Shinro Ohtake’s much discussed scrapbooks, that heave with a feverish sensibility of needing to see and collect and record everything.

Work by ‘‘outsider’’ artists features heavily – from the sculptures and exquisite embroideries of the late Brazilian Arthur Bispo du Rosario, who tapestried the messages he’d received in a visitation from Christ; to the mythological clay figures of the severely autistic Japanese sculptor Shinichi Sawada. These works are interwoven, without commentary, into the exhibition and their sense of fragile otherworldliness is brought into sharp relief by Matt Mullican’s performance-driven paintings, completed under hypnosis, which just feel glib and awful by comparison.

The scale of works in the Central Pavilion and Arsenale is always overwhelming but the fluster, disorientation and occasional irritation it provokes is usually punctuated by the accidental stumble across something special. As always, it’s a subjective feast, but to this mind, highlights include Tino Seghal’s Golden Lion-winning performance, Roger Hiorns’s atomised jet engine, Sarah Lucas’s lumpen, anthropomorphic bronze sculptures, Fischli and Weiss’s pithy, playful clay dioramas and Cindy Sherman’s curated photography exhibition within the Arsenale, in particular the striking work of Phyllis Galembo.

Elsewhere across Venice and the Giardini, 88 national pavilions jostle for attention. Not bound by the biennale’s theme, encountering these micro exhibitions usually offers a richer, more articulate experience and there are a number of considerable highlights.

Jasmina Cibic’s off-site Slovenian pavilion is a sharp, subversive riff on the problematics of national representation. For our Economy and Culture features two video works, including a farcical re-enactment of a recorded 1957 parliamentary debate about which artists and art works would be most ‘‘suitable’’ – architecturally, aesthetically and politically – to decorate the new People’s Assembly. Meanwhile, the entire pavilion, a repurposed private residence, is decorated in creepy bug wallpaper. The bug, Anophthalmus hitleri, was discovered in a Slovenian cave in 1937 by amateur Yugoslav entomologist Oskar Scheibel who named it in honour of his German heritage. As a complete work it is darkly brilliant with a surreal, almost inappropriate, humour and is a great example of clever commissioning that responds to the idea of the biennale without being cute or obvious.

.jpg)

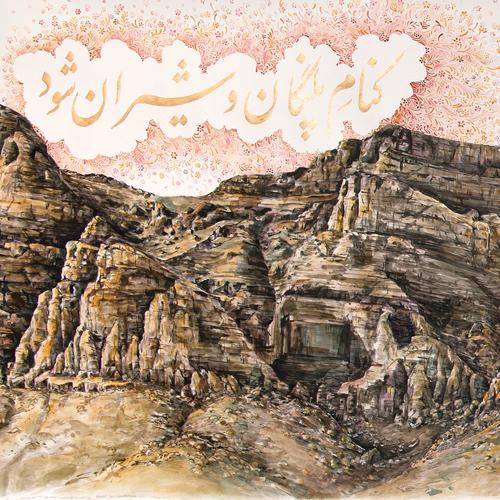

Simryn Gill’s meditation on decay and ephemerality is delicate and quietly beautiful but amid the bombast of the other pavilions in the Giardini, it suffers for its subtlety. The Australian pavilion is due to be demolished and replaced after this biennale and Gill’s work brings an integrity and narrative to the building which otherwise suffers the unfortunate architectural fate of looking like a demountable classroom.

In the off-site Irish Pavilion Richard Mosse presents The Enclave, a staggering meditation on horror, beauty, war photography and the ways in which contemporary society seems to accept and consume images and narratives of violence. With Trevor Tweeten and Ben Frost, Mosse infiltrated armed rebel groups in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo where, in a surreally nightmarish fashion, he recorded their training, ambushes, rallies and patrols. Using discontinued military surveillance equipment that registers an invisible spectrum of infrared light designed to detect camouflage, Mosse’s 16mm footage is consequently rendered in mesmerisingly vivid, psychedelic hues of magenta, lavender, cobalt and puce. Intercut with lingering shots of the Congolese landscape with a soundtrack of haunting field recordings, these sublime, disturbing images stamp themselves in the mind. The intellectual struggle between the awfulness of the images and their absolute beauty, what Mosse identifies as a ‘‘vicious loop of subject and object’’ is strangely pacified by the dark space and absorbing six-screen installation. It’s impossible to not be drawn into this visual lullaby of horror. It is an extraordinary work.

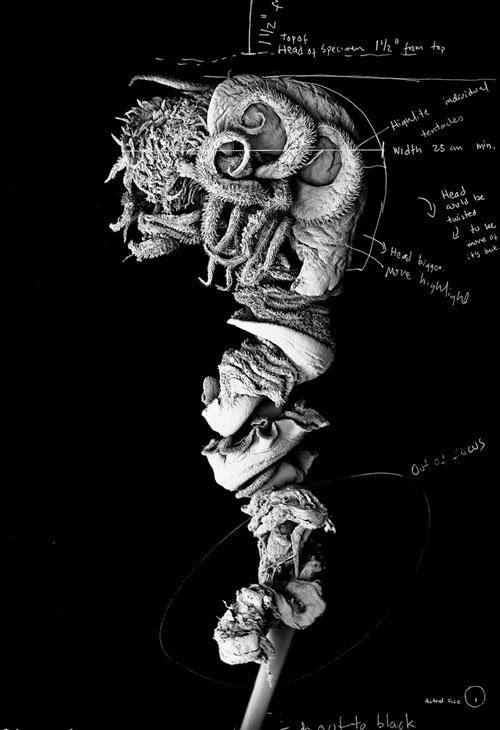

Other highlights include Berlinde De Bruyckere’s crippled, post-apocalyptic tree in the Belgium pavilion, cast in wax and devastatingly human with its broken, supine limbs and mottled flesh; Vadim Zakharov’s dark, wonderfully theatrical exploration of greed and lust in the Russian pavilion; and Alfredo Jaar’s malevolently sinking model of the Giardini in the Chilean pavilion. Romania’s endurance performance piece, physically re-imagining and representing works from previous biennales, from Picasso’s Guernica to Sophie Calle’s Take Care of Yourself. An Immaterial Retrospective of the Venice Biennale is a work that really only offers something to art-world types but there’s something refreshing about this stripped back version of the biennale. Particularly after two days spent wandering through Gioni’s epic, largely impressive, Palace.