Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s work inhabits the chasm between Indigenous history and improvised settler culture. She speaks in the vernacular of those who live and work west of the Great Dividing Range, where rust has supplanted traditional ritual but where blood still binds people to place. Her art tells the story of a country on which open forests and native grassland have been replaced by paddocks planted with improved pasture.

Connelly-Northey is not alone in salvaging materials from the rural past, for there is an extensive cottage industry focused on repurposing corroded metal with artistic intent. From armoured figures of Ned Kelly on sale at Jerilderie, to Mallee Fowl rejigged from ‘dogs’ scavenged at an abandoned rail-track at Wycheproof - there is an artist in every second country town who specializes in making figures from weathered cast-offs. But Connelly-Northey’s work is distinguished by an economy of form, her minimally altered materials speaking of time and exposure to wind, sun and rain. There is no hint of kitsch, sentimentality or jingoism. Like the assemblages of Tom Risley, Theo Koning and Rosalie Gascoigne she materialises the poetry of place with found objects.

I first encountered Connelly-Northey’s work at the 2003 RAKA Awards at the Ian Potter Museum of Art at the University of Melbourne where an installation of coolamons, string bags and digging sticks made an instant and indelible impression. While not underestimating the singularity of her artistic vision, there was a compelling sense of inevitability about the work – it was evident that she would become a major voice in contemporary Australian art. Connelly-Northey’s poetry rests in conjuring the purity of traditional utilitarian forms with the refuse of rural industry – nothing is wasted. The economy with which she goes about her task recalls the way in which Aboriginal carvers create weapons with a minimum of effort, as if releasing them from the living form of a tree with a few well placed axe-blows.

Her work also relies on familiarity with the protocols of rural culture, for access to private land is tricky to negotiate and the scrap heaped into disused dams is never totally discarded. Such sites can be ‘keeping places’ in which farmers lodge machinery, corrugated iron and wire for future use. Old-timers recognize the value of dumps that may provide exactly what is needed to fix that thingamajig, at a pinch. Stuff randomly tossed into pits is left to degrade gracefully, the process occasionally accelerated with fire, as farmers seek to eradicate snakes sheltering under sheets of iron. Curator Julian Bowron told me that the artist takes particular care to foster her relationships with landowners with good tip sites, at times even requesting that they light up their ‘fire pits’ to heighten the chroma of rust on the objects that they harbour. Hers is surely an original take on the ancient art of ‘fire-stick farming’.

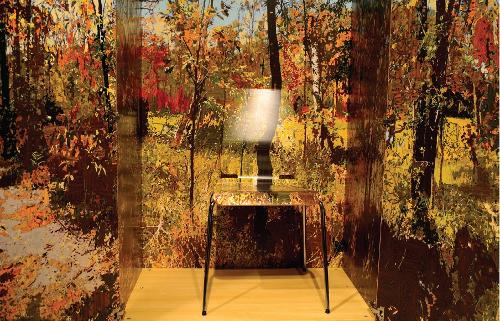

The exhibition Waradgerie Weaver presented at Swan Hill Regional Art Gallery in the summer of 2012/13 is something of a homecoming, for this is the site from which Connelly-Northey’s stellar career was launched a little over a decade ago. The exhibition coincides with her inclusion in the Asia Pacific Triennial; in fact her work for Swan Hill is made from the off-cuts from the massive ‘narbongs’ (baskets) shown in Brisbane. Her work at Swan Hill was more intimate however, consisting entirely of many small vessels, clustered taxonomically according to their form and the material used in their construction.

Objects are as simple as a square of weathered weld-mesh, folded to form a triangle and attached to a bent wire handle to become a string bag. Other baskets consist of heavy grates, extracted from the belly of an ancient harvester, whose perforations mimic the tightly knotted surface of fibre-craft. The shadows cast by these forms, accentuate the minimal means employed in their transformation from tip to white cube. Bowron’s wall text suggests that “the interrelationships between weaving, drawing, painting and sculpture are clear to see. The artist knows that in a pure abstract sense to weave is to draw in space and to draw in space with wire is to make sculptural forms. The colour palette of oxidised and burned metals is both vivid and subtle evoking all the richness of oil paint”.

Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s sensibility is distinctive and unnerving, her work a gestalt, issuing from her economy of means. Swan Hill is an ideal site to consider her achievement over the decade. For here, at home, her work is at its most intimate and meaningful, speaking the vernacular of the land from which it arose.