In China, portraiture has traditionally revolved around the power and orthodoxy of the state. This is exemplified by the imperial court paintings of emperors and officials as well as by the social-realist portraits of cheerful flag-waving workers and valiant soldiers from the Cultural Revolution. These portraits were, in the main, imagined, idealised and generic images of individuals or groups of people that did not seek to represent or express the physiognomic likeness of the subject with which portraiture in the West is associated. Following the introduction of the Open Door policy in China, modernisation, urbanisation and consumerism during the 1980s gave rise to new forms of self-expression in art in which the individual, rather than the state or nation, emerged forefront and centre in art.

GO FIGURE: Contemporary Chinese Portraiture, curated by Dr. Claire Roberts, highlights the ways in which this emergent sense of individualism manifested in Chinese art. This is explored within the context of portraiture which is broadly defined in relation to the role of the individual in Chinese society. The exhibition is divided into four main themes which address the idea of 'face' in Chinese culture, politics, the body, and youth culture. It comprises mostly paintings produced during the 1990s by some of China’s pioneering contemporary artists including Fang Lijun, Zhang Peili, Yu Youhan, Wang Guangyi and Liu Xiaodong, as well as more recent digital and installation works by younger, lesser known artists including Chen Wei, Kan Xuan, Zhou Tao and He Xiangyu. These works have all been drawn from the collection of Uli Sigg, a Swiss businessman, who has amassed one of the largest and most important collections of contemporary Chinese art, comprising some 2,200 works. Roberts selected approximately fifty works for this exhibition which was a snug fit for its venues: the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, which exhibited the majority of works, and the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Sydney.

The subtitle of the exhibition, ‘contemporary Chinese portraiture’ suggests there is a Chinese element or essence these art works share. However, upon viewing them collectively, one of the most striking aspects is their conceptual breadth and stylistic diversity, especially works created from the late 1980s and through the 1990s when the desire for artistic freedom and self-expression was strongest. Having said that, the works in this exhibition are China-centred and, conspicuously, the vast majority of portraits that portrayed a person or a group of people are almost exclusively of Chinese people. Jing Kewen’s painting No Clouds at the Great Wall (2000), which features a delegation of Africans with Chinese officials at the Great Wall, is one of the exceptions. Based on a photograph taken in the 1970s, Jing’s work subtly yet critically reflects upon changing political and economic relations between China and Africa today.

Another is Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s collaborative interactive installation, entitled Old People’s Home (2007) which occupies the main gallery at Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation. It comprises thirteen elderly life-size men, several of whom uncannily resemble world leaders, including Fidel Castro and Yasser Arafat. Although dressed in official attire these figures have been stripped of their authority as they are shown decrepit and slumped in motorised wheelchairs that aimlessly cruise and collide in the otherwise empty gallery space. The work has broad audience appeal for its technical virtuosity and humour, but it also raises some serious questions relating to leadership, power and their decline.

Images of China’s former leader, Mao Zedong, are prevalent throughout and his voice, recorded in He Xiangyu’s audio-visual installation resonated in the exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Mao’s portrait, which still looms over Tiananmen Square today, is arguably China’s most famous. Since the 1980s, his iconic fleshy face has been appropriated, deconstructed and subverted by many Chinese contemporary artists including Yu Youhan, Shen Shaomin and Wang Guangyi, who have imbued it with new meaning. Their works are included, along with Yue Mingjun’s painting, Founding Ceremony, 1997, parodying a famous painting created in 1953 that commemorated the founding of the People’s Republic of China. However, in Yue’s painting, the artist completely erases the figures of Mao and his Communist officials who were depicted in the earlier painting speaking to the masses in Tiananmen Square. Song Dong’s two photographs from his Breath, 1996, series, which portray the artist literally breathing new life into Tiananmen Square, offer a thought-provoking counterpoint to Yu’s comparatively stark and dispassionate work.

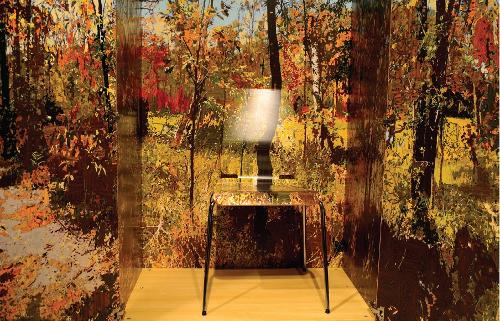

The vast majority of works focus on China’s history and politics. An exception is Wang Jianwei’s insightful and also humourous two-part video entitled From the Masses to the Masses, 2000, which sensitively captures the banality as well as the idiosyncrasies of everyday life in China. Street scenes, including a parade of inflated walking objects and an obese pig perched on a motorbike, are juxtaposed against close-up images of rows of children from the Communist Chinese Youth League, representing China’s future generations. Their faces reflect both hope and uncertainty about what this future will bring. Ji Wenyu and Zhu Weibing’s captivating miniature installation entitled The Environment Here is Great, 2006, also meditates on the future. Within a small glass dome three small figures, a father, mother and their only child, are assembled signifying China’s nuclear family. An air-conditioner and a bird cage are their only possessions and, clutching each other, they look forward to a better future.

GO FIGURE: Contemporary Chinese Portraiture is a thoughtfully presented exhibition that explores the role and meaning of the individual in China today. It also demonstrates how the concept of the portrait as an art form has changed considerably during the last two decades and more as contemporary artists are no longer bound by the orthodoxy of the state. This exhibition is the result of an inspired collaboration between an international art collector, a curator of Chinese art, and two leading galleries and it offers a unique opportunity for Australian audiences to view works by some of China’s most celebrated artists up close. In fact, it may be our last opportunity given that Sigg has just (June 2012) donated this much-prized collection to the new M+ museum in Hong Kong.