When the anthropologist Robert Tonkinson arrived at the Jigalong mission to study the Aboriginal people living there in the early 1960s, he discovered that they were less in need of study than the white missionaries running the place. Tonkinson reported that the Martu were doing fine all things considered, and that it was the Christian missionaries who really needed the help. A new exhibition of Martu art in Western Australia gives us a similar message, but with all the pizzazz of new media. Testifying to the Martu intimacy with vast stretches of country are multiple videos of them burning it off. There are lines of flame reaching into what appears as an endless horizon, the Martu dotted along it with firesticks in hand. There are women appearing and disappearing into grasslands, hunting out goanna with big sticks. There are paintings whose dotted and coloured variations shape the image of spinifex plains at different stages of burning, regrowth and burning once more.

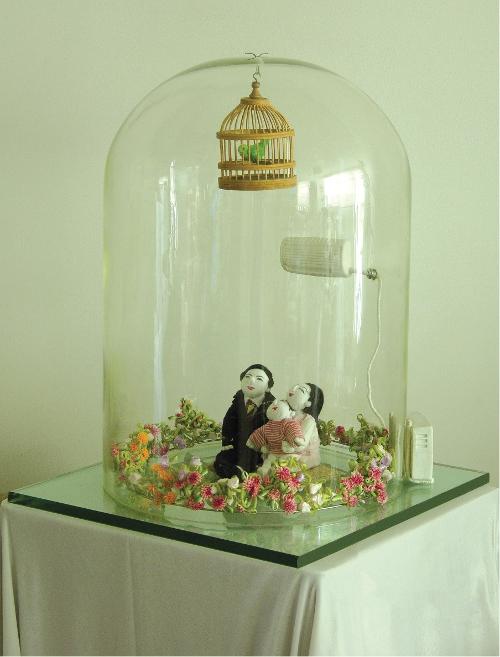

This is a spectacular and groundbreaking show that uses both collaborative and ethnographic methods to bring forth the kinds of immersive spectacles that we have come to expect of the best of contemporary art. It is colourful and rich with the detail of Martu lives without the burden of museum informatics. A Martu basket is translated into an inflatable bouncy castle for the kids. An animation brings a horrific cannibal story to life, and brings forth the force of Jukurrpa stories, the reason that they have thrived through centuries of deep time.

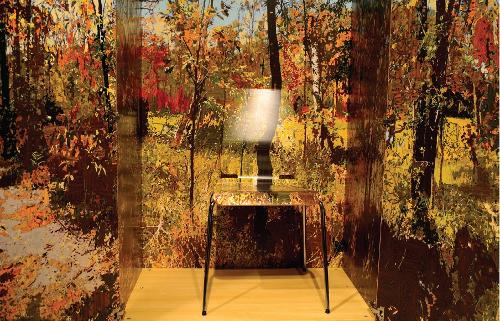

How did it happen? How were the humble rooms of the Fremantle Arts Centre transformed into an immersive experience of Martu culture that impresses its viewer rather than patronises them, that elevates the senses rather than drags them down into some kind of a cross-cultural experience? Two things. First are the collaborations. Lynette Wallworth’s three screens featuring Martu women walking across the desert and spinifex, hunting and posing for the camera, creates a lifeworld within which fire, lizards, spinifex, sticks and women all play a role. An animation of paintings by Yunkurra Billy Atkins and directed by Sohan-Ariel Hayes is also a breakthrough work, as we fly down into the paths that Yunkurra has painted for the cannibals of Lake Disappointment, to witness their unspeakable violence. These are simultaneously light and serious works, as we are carried away by Martu cosmogony, while smiling all the time.

From such so-called new media works it is possible to see the main room of the Fremantle Arts Centre, skied with brilliant paintings of salt lakes and spinifex, as an installation of new media works itself. For painting has always been a new media to Western Desert societies, no more or less modern than an iPhone or a GPS. The Martu have adapted to new materials, new species, while all the while remaining the same. Amongst the paintings the use of great white expanses distinguishes work by the late, great Muni Rita Simpson as well as that of Jakayu Biljabu, Mulyatingki Marney and Nancy Patterson. White may simulate the surface of a salt lake or limestone country, and also orients a masterful, four metre high collaborative work by a group of Martu women, waterholes dotted around it. Also impressive and lining a corridor are some small and ghostly pencil drawings by Mukki Taylor of figures and trees. Their brevity provides a gentle counterpoint to the immensity of the desert that features so impressively in the rest of the exhibition.

Which brings us to the second thing that enabled this exhibition to take place, which is mining company BHP. Let’s not be naive. This was a hideously expensive show to mount, running to $380,000, but it was worth every dollar. It empowered a loose coalition of artists and curators not only with time and vehicles, but also freed them from both bureaucratic complexity and commercial necessity. The sense of freedom that permeates the show, through its multiple visions of desert country, comes too from the Martu themselves, who have long carried with them its sensibility. In this exhibition they convey a deeply compelling joy that comes as much out of an intimacy with nature as it does from the excitement of trying out genuinely new ideas in the exhibition space. As the visitor moves between rooms filled with the theme of fire, to the main gallery skied with paintings of country, it is difficult not to be humbled not only by the lifeworld that unfolds between them, but by the way that the spectacular strategies of contemporary art have here been appropriated for reasons of gentle and genuine spirit.