It's not often that we see exhibitions premised on the idea of futurity but 2112, curated by Linda Williams, takes as its subject varied projections of life on earth 100 years hence. An array of local and international artists ruminate on what the future may look like through a range of works that show telling points of overlap nested within an overarching presentiment of dystopia.

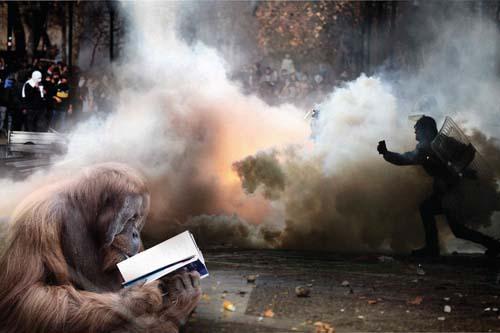

Nearly all the works take as their point of departure the less palatable realities of the present: the seemingly limitless economic imperialism of the world by corporate multinationals; global climate change; the intensification of extreme weather events and concomitant chaos; mutations in mammalian species; and the escalating threat of the extinction of the earth’s indigenous flora and fauna.

The Danish collective Superflex presents a vengeance fantasy on the most recognisable of junk-food conglomerates in their video Flooded McDonalds, depicting the generic interior of a franchise store gradually inundated with water. An ungainly mass of detritus including water-logged fries, polystyrene cups and a plastic cast of the eponymous mascot floats on the water’s surface, the gentle undulations of the rising tide creating an unexpectedly mesmerising work.

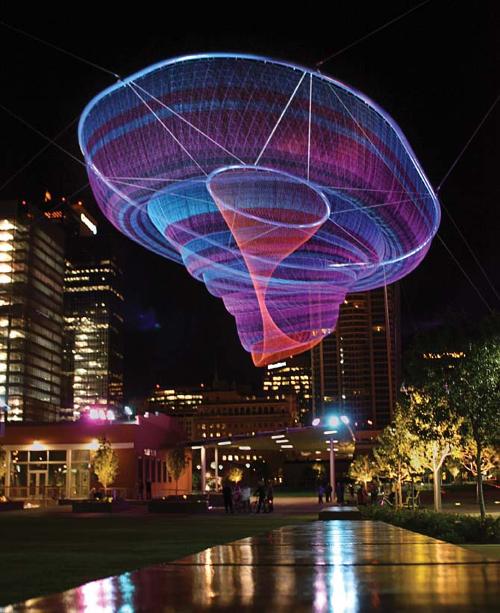

The increasing prevalence of natural disasters - the disastrous tsunami in Japan in 2011, the flooding of Brisbane and Bangkok the same year, Indonesia’s savage tsunami of 2004 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005 – remind us of nature’s ineluctable capacity to unfurl vile tempests and unleash devastation. The frailty of the human gesture in the face of such potential force is delicately captured in Thomas Doyle’s Well Enough Alone: a small-scale sculpture featuring a toy-sized figure at the bottom of a trench tentatively raising his hand towards a huge, ossified wall of water. The tiny figure’s hand is on the verge of grazing the water’s edge; the precarious equilibrium of the bizarre scene is impregnated with portent as if we are witnessing a micro-second before an avalanche falls.

Misaharu Motoda’s exquisitely rendered lithographs present visions of abandoned metropolises; iconic city centres of Tokyo and Sydney desolate and partially destroyed in the post-apocalyptic haze of an unnamed catastrophe. The meticulously drawn prints depict recognisable districts with the glass and metal facades of the urban architecture shattered and torn asunder, redolent of the dystopic landscapes of the bombed cities of WW2 or more recently, the east coast of Japan.

Continuing the dystopic theme are Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre’s photographs of Detroit. Unlike the other works – imaginings of futurity – these photos depict the city in its contemporary state – office buildings, homes and schools vacated and left to decay, animated only by a vandal’s spray can. In Adams Theatre, Detroit, the Edwardian theatre – a magnet for the city’s glitterati in the 1920s – lies desecrated in an almost surreal convergence of ruin and grandeur. Detroit was America’s flagship city for capitalist entrepreneurship in the early decades of the 20th century, its accelerated prosperity driven on the back of the ascendant corporate giant Ford. By the century’s end, the severe contraction of the car manufacturing industry saw the city transform into an urban wasteland overrun by gang violence, poverty and depopulation.

For other artists, the instinct to preservation dominates, in particular the quest for museological archiving. Justine Cooper’s photos depict the storerooms of the American Museum of Natural History, one door ajar to reveal a cluster of suspended leopard hides from the Congo; another photo portraying the aged, cloth-bound catalogues listing the museum’s accessions. Lyndal Osborne lines a wall with illuminated glass vitrines filled with faux-botanical specimens as imaginary versions of seed forms inspired by the Millennium Seed Bank archive in the UK, while Stephanie Valentin displays eerie photographs of cut-glass vases and bowls clustered in a vast, nocturnal plain, as if these might be the only objects left behind from an extant civilisation.

Most of the works in 2112 are united by a noticeable absence of the human figure. When they appear humans seem less familiar, as in Patricia Piccinini’s sculpture Game Boys Advanced where two teenagers stand fixed in rapt attention over their electronic game, their faces sagging and wrinkled in repellent signs of premature senescence. It’s not a stretch to conclude that the majority of these artists harbour grave doubts about humanity’s future. The impact of transgenics as well as climate change, native species loss and the earth’s deterritorialisation may well lead to humanity’s marginalisation.

The philosopher Paul Virilio once observed that everything that shapes the novelty of tomorrow is already detectable in the present, residing in the imaginings of each person. If this is so, then the works in 2112, while allegedly projecting pessimistic visions of the next century, speak pointedly of the present as much as the future.