It's a basic fact of life that Australian state galleries are constantly under attack for not showing enough work by local artists. It’s usually local artists who lead the charge. The Queensland Art Gallery may have silenced the angry mob, for a while at least, with its extravagant display of work purchased by Brisbane philanthropist James Sourris.

This wasn’t the usual token gesture. GOMA devoted one its enormous main galleries to presenting the principal players in the local scene as major artists, shown in the company of big names from elsewhere in the country and abroad.

Sourris had originally planned to make funds available so the Gallery could afford to buy the kind of important older works that form the core of collections in other state galleries. He credits former art dealer Peter Bellas with convincing him that Queensland had missed the boat as far as building a significant collection of heritage art was concerned. The paintings by Streeton, Roberts, McCubbin et al now apotheosised on tea towels and owned by public institutions around the country were originally bought as contemporary art by collectors in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide, but not Brisbane.

Bellas advised Sourris to buy new rather than old (very sensible advice for a contemporary art dealer to give). The thematic rationale of the collection is an overview of art at the beginning of the new millennium - works made between 2000 and 2010. The guidance of Bellas and that of his successor Josh Milani is very evident in this exhibition, which is dominated by artists represented by Bellas Gallery and subsequently by Milani Gallery.

This is probably inevitable in any exhibition consisting primarily of work by the most prominent contemporary artists in Brisbane, although the strongest representation of non-Queensland artists provided by the work of Vivienne Binns, Jon Cattapan, Robert Hunter, Tim Johnson and Gareth Sansom, was also bought from Bellas. An initial glance at the exhibition left the viewer with a sense that its subtitle, 'Ten years of contemporary art’, could have been more accurately expressed as ‘Ten years of Australian contemporary art’, or even ‘Ten years of Bellas art’. For better or for worse (I think for better) this view of recent world art is very much the view from Brisbane. Twenty years ago Brisbane was not a significant location in the world according to contemporary art, and nobody would have been particularly interested in its views. That’s changed somewhat.

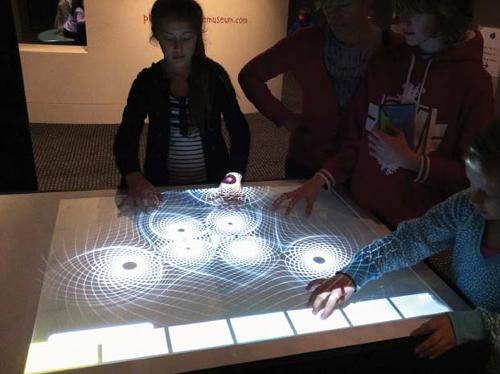

James Sourris had a successful career as a movie exhibitor and multiplex developer, and his association with film provided the initial focus for his patronage of the Queensland Art Gallery. He began forming a contemporary art collection for the Gallery in 1999, in collaboration with Doug Hall, who was then the Gallery’s Director. Hall used the money to buy video. This is the area where the exhibition frees itself from parochialism. Australian video is seen in a global context, with works by Justine Cooper and John Gillies screened together with pieces by Bill Viola and William Kentridge.

The generosity revealed by the exhibition is more than a matter of money. Artists are given proper representation, usually with multiple works. Viewers can get a real sense of the diversity of Eugene Carchesio’s work, and Gordon Bennett is included along with his alter ego John Citizen.

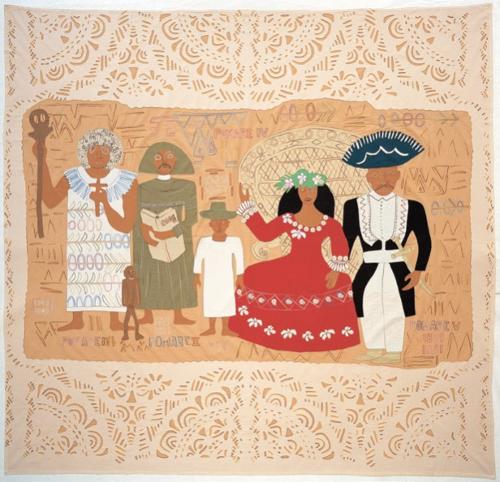

The single most important historical fact illustrated by this exhibition is the identity of Brisbane as the principal Australian city for the production of Aboriginal art during the past ten years. The Sourris collection includes an ambitious sampling of the proppaNOW collective. Because of the highly sophisticated, perhaps somewhat effete, theorising often applied to Richard Bell’s work (which stands up to it perfectly well) it was good to be reminded by the wall-sized paintings in this exhibition that his principal objective is putting the boot in. Gordon Hookey’s five metre wide painting of militant armed kangaroos confronting a line up of Taser guns is physically intimidating.

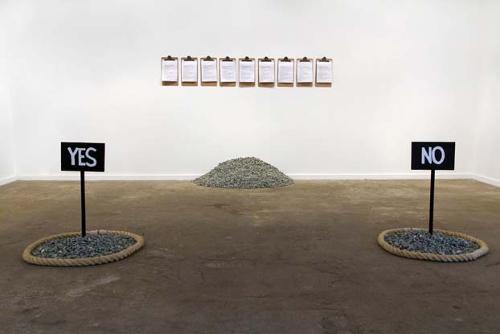

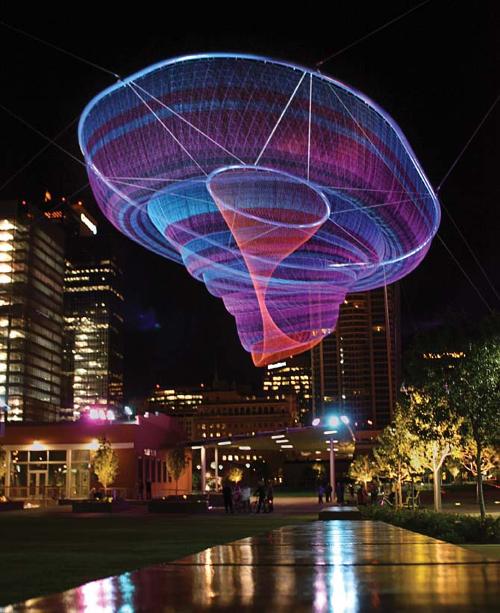

As Julie Ewington points out in the first essay in the exhibition’s fine big catalogue, there are two paths through the collection, one revealing our unsettled times, the other exploring pure beauty. The jarring, often hilarious, Luke Roberts photographs popping like flashbulbs in the face of our social and cultural insecurities illuminate one path, the intensely refined, rather minimalist Aboriginal works from Arnhem Land illustrate the other.

Naturally the paths occasionally become entangled. Madeleine Kelly’s mysterious painted parables are too oblique for social criticism and too troubling for lyrical fantasy. The two paths cross with the sharpness of a grid reference in the huge portraits by Vernon Ah Kee. The monochromatic images appear serene, and they are, but they also suppress a boiling anger that’s made stronger by being contained.