Painting on canvas so dominates artistic production in Central Australia that an exhibition under the banner Contemporary Ceramics from the Desert seemed like it could be an over-stretch. In the Aboriginal domain ceramics is a minority art. In this year's Desert Mob, for instance, of almost 300 works, only ten were in clay. Amongst non-Aboriginal artists practising in The Centre only Pip McManus immediately sprang to mind as a ceramicist and her recent trajectory has been away from clay as a primary material. When she won the 2008 Alice Prize (against national competition), it was with a video work Ichor that recorded the disintegration of an unfired clay figure over 55 minutes. Her two preceding major works had been in the form of a series of clay tablets, whose surface carried their meaning. Ichor was a radical departure and McManus has not returned since to work that yields large fired ceramic objects.

This is the case for her contribution to Sequences and Cycles. Weight for weight, clay is a minor material in her eight pieces yet interestingly it is core. In each piece a tiny clay figure - childlike yet ageless, and without strong race or gender characteristics – puts humankind centre stage in relation to what is elemental. With eloquent simplicity and playfulness McManus reminds the viewer that it is crunch time for human action to protect that on which we depend – Water, Earth, Fire, Air (the titles of one series, written into the work as Greek symbols in elegant steel); that our personal sphere is implicated (the Home of a pair of works); that the future will be shaped by what we do in this moment (Vista 1 and 2); that this is our task, to which we must harness our ingenuity (Wheel).

The clay of the figures speaks to a past and a future beyond history, or ready personal comprehension, to natural processes that predate our species and will outlast it. The imprint that the figures bear of the human hand, that they are fashioned in our likeness, endowed with an endearing, unsophisticated character, and that they are tiny, attaches them to the intimate present.

The exhibition curators set the direction for the exploration of big themes with their title as well as by specifying that the work needed to reflect in some way the artists’ experience of the desert. Not surprisingly then this small exhibition (six artists, thirty-five works) coheres around a quality of essentialism, of fundament – the desert has a way of summoning this response.

Like McManus, Mel Robson, a ceramicist of national repute who has recently arrived in The Centre, has used miniature scale and repeated forms to conjure this encounter with the elemental. The 'stones’ of her series Sticks and Stones,fashioned from slipcast porcelain, evoke a personal present intersecting with the long passage of time. They are river pebbles, worn smooth by countless flows – you can just imagine holding their coolness on your tongue or in the palm of your hand. You can also just imagine Robson, the new arrival, walking in the dry creek beds of the desert, stooping to pick up the originals of these small perfections and discovering in them the surprising memory and promise of flowing water, seeing their pale smoothness reflected in the tall straight trunks and spreading branches of ghost gums, sticks lying beneath them like small bleached bones. With her flawless, unglazed porcelain she has responded to a limpid quality in the desert landscape, a note that is not often sounded.

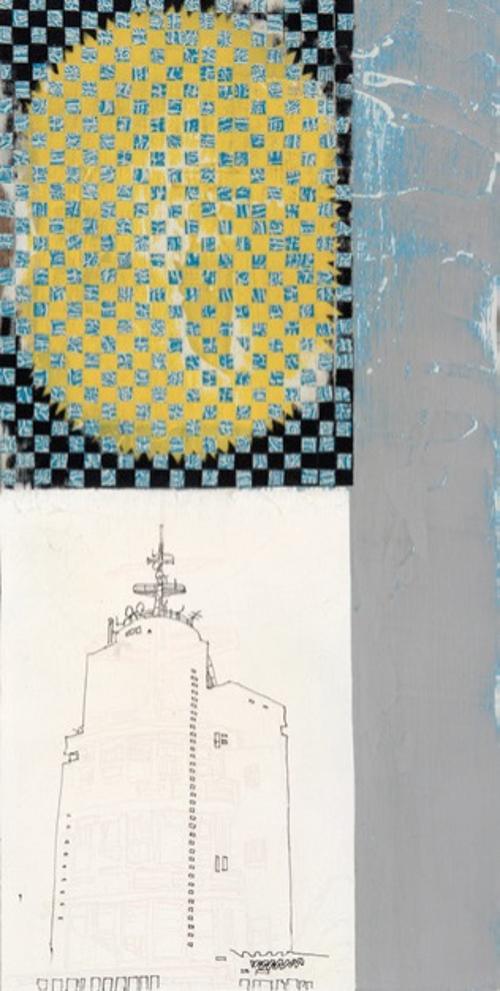

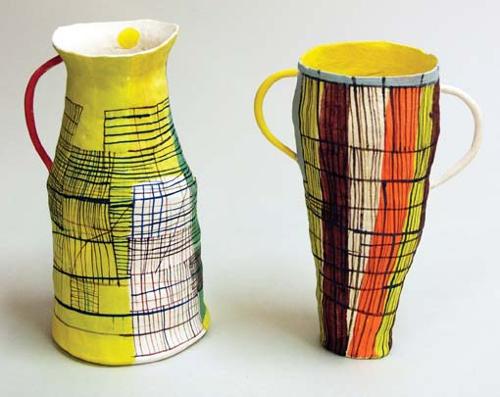

The large scale of Suzi Lyon’s work makes for a stimulating contrast, whileher concerns – mounting a critique of the relentless cycle of production and consumption – are very close to those of McManus. There is a cross-over in subject – two of her four sculptural pieces share a title with McManus’ work, Home and Earth – and both artists are concerned about the way in which firing clay causes a permanent transformation of the material, ensuring, in McManus’ words, that it does "not quietly return to earth". Going further, Lyon has constructed her forms using dug local clay, recycled clay, mixed with cow and camel dung, straw, grasses and broken down termite mound, and has used bushfire ash, dung and termite mound as render. They have a moving childlike yet ageless quality – again a link to McManus’ work – drawing as she does on archetypes (two types of tower for Home and Refuge, two types of vessel for Welcome and Earth).

Aesthetically Amanda McMillan’s work could not be more different. She evokes advanced industrial decay, with her sections of broken pipe covered in a dessicated clay skin as if diseased, and a kind of mania in her seemingly rational collection of earths in tiny plastic bags. That she shares the environmental concerns of McManus and Lyon is clear, with her emphasis on the disruption of natural cycles. Her use of clay, however, is less integral to her meaning.

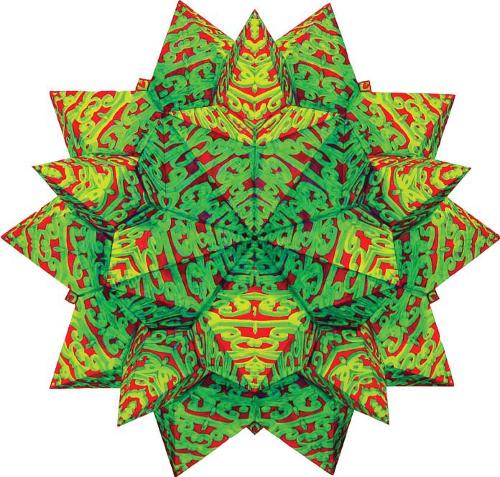

The cycles of the natural world are intrinsic to the concerns of the two Aboriginal artists Pantjiti Lionel and Patsy Morton. Themes of regeneration are common to both, represented figuratively in applied decoration to their forms. Morton’s hand-pressed coolamons, given their association with nurturing, are well suited to the themes. Lionel’s choice of form appears more arbitrary.

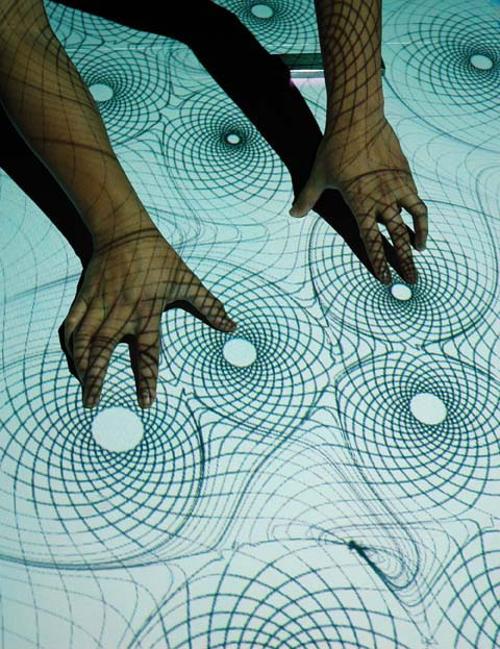

This exhibition was accompanied by a show for emerging ceramicists; a seminar with guest speaker Prue Venables, the creative director of Adelaide’s JamFactory Ceramics Studio; and a well-attended ceramics workshop for young people. As a way of stimulating interest in this art form in the region, of revealing unsuspected practitioners, of teasing out some of ceramics’ contemporary issues, it was certainly a success. I expect we will see a sequel.