Peter Sharp has said he likes art that betrays the way it is made. If blurred distinctions and paradoxical questions about process and media are hallmarks of Sharp's work, then his recent exhibition Shadowbox - the Desert Paintings fulfils this criteria admirably.

It is difficult to describe Sharp’s work simply as 'abstraction’, the canon to which his paintings could easily be assigned for their expressive, gestural line and flat fields of colour. His work captures the physical traits of abstraction, yet resists this classification in its fixation on the natural world and its organic figures and forms.

Sharp’s previous shows have focused on aspects of the environment, such as the sea and its creatures in Close to the Bone (2006) and the anatomy of a spider’s web in Spider (2007) and Web (2008). The starting point for Shadowbox: The Desert Paintings is also the physical world: the desert landscape of Fowlers Gap in far western NSW.

In May 2011, Sharp travelled there with 12 other artists for the sponsored expedition Not the Way Home. However, instead of rendering the environment pictorially, he ended up collecting objects and binding them together to form small, conglomerate sculptures.

His recent exhibition reveals a fascination with these objects’ textures, colours and formal configurations. The fragile forms in 15 small charcoal sketches, arranged in an installation on the gallery’s opening wall, could be carbon readings of the earth’s rocks, sticks and stones. They reinforce the input of observational drawing; however, for Sharp, the process also involves looking closely at natural events and trying to turn that experience into painting.

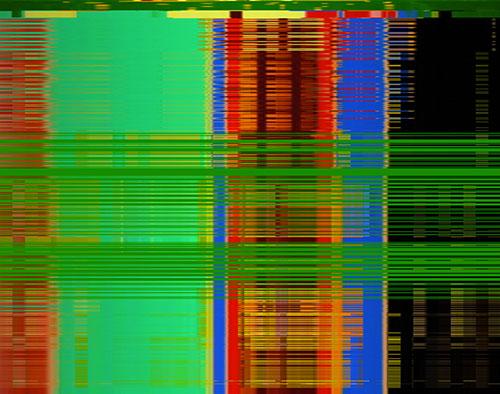

Creating a dialogue between physical elements and emotional experience upon a two-dimensional plane is a perennial challenge, yet under Sharp’s control, seven large desert paintings, which are the centre-piece of the show, interact between these two worlds successfully. The artist has explored new techniques to produce metaphysical yet earthly imagery. Each picture plane is built up then toned down: white acrylic on linen is stained in desert-brown glaze, then sanded back by hand to produce a facsimile of the surface beneath. The content of these works sits comfortably with their scale and the overall effect is balance and serenity, as in Mirage.

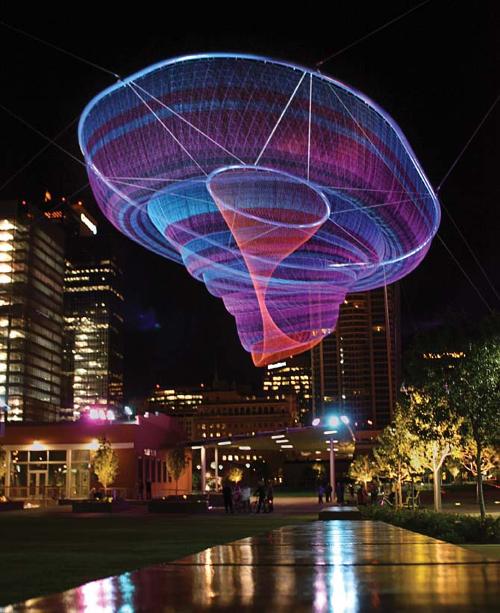

Yet energy and movement undulate between media, as we sense a shift in approach from brushes and paint to timber and sandstone, in order to explore, more stringently, the solid particles that create the texture and shape of an object’s physical form. Three nebulously formed sculptures work in unison with the pictures, introducing relationships between positive and negative space and contrasts between shadow and light.

There is an honesty and modesty about this body of work; colour has a symbolic function as well as emotional facility, presenting authentic samples of the desert’s brown earth and blazing blue skies to strong effect. If there is a simple message at its core, then it must be to take pleasure in seeing things for what they are. But then again, things aren’t what they appear to be. The small particles of a rock or twig, its irregular line and tawny colour are abstracted again into another unfamiliar morph. What we see is not an object per se but a conduit between the artist’s techniques and his way of seeing the object’s properties and personae.

These parallel views, from within and without, up-close and then far away, are also a reminder that it is not what we see but how we interpret that counts. A case in point is a tall shaft of chain-sawed timber, incised and seared, then painted blue. As it reaches up towards the sky, its title, Measure, enlightens our perspective with the playful question – how tall is the sky?

Measure holds the echo of a totemic sculpture or burial pole at its centre, an important emblem of Aboriginal culture. The Indigenous symbolism inherent in this work is a reminder of the land from where the materials, objects and ideas first came. Sharp’s work often envelops Aboriginal ways of seeing in his layered rather than linear views of the environment. This vantage point is articulated via the paintings’ granular textures, and the angularities of three-dimensional sculpture present the metaphor in refined physical terms.

Shadowbox – The Desert Paintings is a finely-wrought show in its vision and breadth, and I can only look forward to the artist’s major retrospective at Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Art Centre in March 2012.