Colin Story is a familiar face in the Western Australian port of Fremantle; some know him as a registered builder who sensitively redevelops the architectural heritage of the city, others know him as a passionate art collector but very few know him as an artist. However, Story’ s early studies in Art History have grown over the last three decades into an extensive understanding of the history and philosophies of art and a significant collection of contemporary art and non-Western artefacts. In Story’s first exhibition inconstruction he presents an array of objects and photographs (all obtained from the building projects he manages) that question and celebrate the nature and history of art.

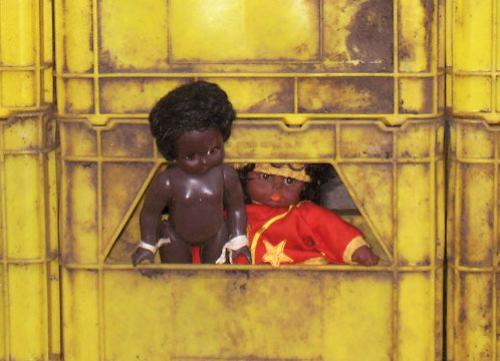

Story’s objects include a used sanding belt from an industrial door sander, old linoleum tiles, scraps of MDF on which tradespeople have tested products and discarded plasterboard. The objects are presented as they were found but recontextualised in the gallery space, providing the opportunity to consider them as Story’s responses to his everyday life or to his interest in the ideas that underpin Modern art.

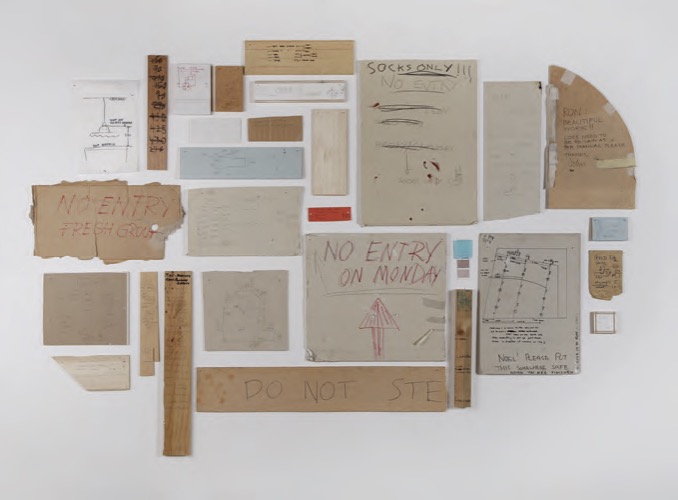

cloud (the things we say to each other) is a collection of handwritten signs hung in an oval-shaped cluster. Notes written on pieces of whatever material was at hand, tell us that there is NO ENTRY FRESH GROUT or that we should proceed in SOCKS ONLY. Calculations, sketches and advice about the floor being too damp to properly sand jostle with a recipe for roast potatoes (with olives and parmesan) and a list of horses in a Melbourne Cup sweep. Together, these signs become an evocative, multi-panelled reflection of mateship and days at work.

The painterly concerns in Modern art of colour, texture, composition and rhythm are acknowledged and honoured in Story’s ‘found paintings’. untitled (orange) is a sheet of plasterboard, the exposed areas of which were once painted tangerine so that an irregular rectangle of searing colour now sits off-centre on the white plasterboard surface. Story has reclassified this found object as a colour field painting.

His photographs of found compositions achieve the same objectives. Images of sanded floorboards or damaged walls become abstract compositions of marks and colour. These works immediately draw attention to the aesthetic qualities of the Moores Building with its whitewashed limestone rubble walls, exposed wooden shingled roof and scarred jarrah floorboards.

A tap attached to a length of timber board, called untitled (i wash my hands) is a homage to Duchamp. Other references to 20th century art exist: a salute to Mondrian can be found in two stacked kitchen cabinets on which the different colours of the drawers and doors are separated by the black lines of the cabinetry itself and a photograph of a field of blue acrow props supporting a concrete raft could easily be called Blue Poles.

Such work could run the risk of appearing to be simplistic interpretations of the iconic artworks and the logic of Modernism. But Story greatly admires Rosalie Gascoigne’s skills in selection and placement and he beautifully employs these strategies in the most successful of his works. For example, untitled (totem) is a block of wood that was used as a sacrificial support on the plate of a drill press. The strange beauty of its ruined state (from the drilling of hundreds of holes upon it) generates a sense of wonder akin to that experienced when examining archeological fragments or mysterious cultural artefacts. Similarly, untitled is a found sheet of masonite on which three rectangles of paint: black, white and black from left to right, are separated by unpainted areas. A column of large holes has been drilled in both the second and third rectangles of colour, revealing the wall behind the work. Whatever its original use, this object has as much aesthetic power as some of its minimalist counterparts in the canon of 20th century art.