.jpg)

Almost forty years ago, a 1974 episode of the British television comedy Are You Being Served? played out in burlesque many of the problems and possible pleasures of hidden camera surveillance now being explored, with various inflections in art.[1] The episode’s title, Big Brother, referred to George Orwell’s prophetic dystopian novel 1984 and not to the later, syndicated television program – named after the novel’s evil panoptical presence – that proved some of its predictions. This Big Brother is set in a Grace Bros department store, where a CCTV system installed to combat shoplifting in Menswear and Ladies’ Intimate Apparel is immediately used to watch the staff instead of the customers.

Over the shoulder of Mr Rumbold the floor manager, the first image we see – in now familiar badly lit, awkwardly angled black and white views with static framing – is the back of Miss Brahms as she bends behind the underwear counter to adjust her tights while Captain Peacock, the floorwalker, takes a sneaky chance to touch her bottom, as he thought, unobserved.

Within one fictional day compressed into less than half an hour, the show gallops from spying, voyeurism and the eavesdropper’s capacity for getting the wrong end of the stick, to the subjects’ awareness of the camera – they avoid it, pose like models, preen as if before a mirror and perform assumed characters with posh voices. Finally, after being chastised and publicly humiliated for doing on camera what had previously been small private acts, the staff turns the system against itself. In a carefully planned sabotage, they act out staged set pieces to destabilise Mr Rumbold, already exhausted and deranged by his fascinated attempt to absorb endless output from multiple cameras. In this fictional world, that small uprising is enough to get the system removed the next day.

The first CCTV system was installed by Siemens in Germany in 1942, half way through the Second World War, to observe the launch of long-range V-2 ballistic missiles aimed at London (now the most closely observed city in the world via CCTV).[2]Commercial CCTV systems hit the market in the United States seven years later.[3] In 1987, Kings Lynn in Norfolk became the first place in the United Kingdom to get comprehensive town centre CCTV – the crime most frequently prosecuted as a result was reportedly public urination by men on their way home at night from pubs.[4] Perth inaugurated Australian public-space CCTV four years later.[5] Are You Being Served? tackled retail surveillance systems when they had been on the market for seven years, so the show wasn’t bringing news but interpretation and awareness of the pitfalls and opportunities of certain kinds of looking.

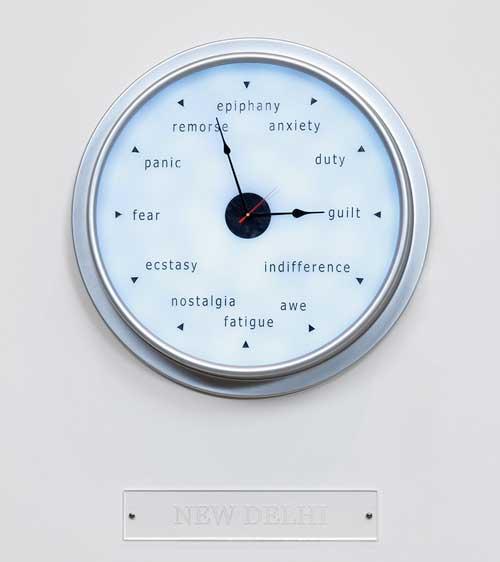

We invited contributions to this issue around these pitfalls and opportunities at the intersection of art and surveillance. We interpreted surveillance broadly to include everything from sustained covert observation and recording by governments to prolonged forensic looking to voyeurism, peeping tomism, stalking and stickybeaking by anybody. We were interested in art made using surveillance techniques and tools, art mimicking surveillance and the effect on art, artists, art practices and audiences of surveillance culture.

We wanted to explore the infiltration of surveillance into private and intimate spaces for political, economic, legal or criminal gain or control; surveillance as a source of entertainment and personal gratification, and surveillance as a response to invasive looking as in self-surveillance, inverse surveillance, or sousveillance. We were curious about how so many surveillance instruments in a culture of relentless watching affected privacy, “community standards” and political activity. We aimed to cover uses of surveillance in art from photography’s beginning – more or less from the time Bentham invented his panopticon prison with its suggestion of invisible omniscience – to contemporary preoccupations with ubiquitous social networking and portable communications technologies.

Although commercial camera phones arrived just over a decade ago, by 2010 consumers had bought around a billion of them: more, someone has calculated, than all the stand-alone cameras sold in the history of photography.[6] It is as though the millions of people (artists or not) who produce and publish images of themselves, their friends, surroundings and ideas in a sort of mass social surveillance (while often being tracked by the devices they are using) are implicated one way or another in the philosophical position parodied in Mr Rumbold and articulated by popular culture figures as well as Wikileaks spokesperson Julian Assange.[7]

Interviewed in the online art journal, e-flux, Assange said a “robust civilisation” needed a comprehensive intellectual record consisting of “everything”, because “everything in the world eventually ... affects everything else”.[8] We have Mr Rumbold as a model of one place this might take us, and the staff of Grace Bros as a model of Assange’s contradictory qualifier: “It makes sense to keep things secret from time to time. It’s a question of who should be keeping the secrets”.

This issue of Artlink approaches the prying curiosity of surveillance, scopophilia, and compulsive and clandestine looking. Texts by artists, curators, writers and academics alongside images by artists who use photography, video, film, electronic networking, installation, performance and painting reveal some of the social implications of watching and the way that watching is framed. From surreptitious encounters to self-exploitation, they uncover uneasy questions about who is looking at whom for power or pleasure. What is clear is that people love to watch.

Footnotes

- ^ Are You Being Served?, Episode four, season 2, written by Jeremy Lloyd, David Croft and Michael Knowles, BBC, UK, 1974.

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Closed-circuit_television (accessed 29 July 2011).

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Helene Wells, Troy Allard and Paul Wilson (2006) Crime and CCTV in Australia: Understanding the Relationship p2. http://epublications.bond.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1071&context=hss_pubs&sei-redir=1#search=%22first%20cctv%20australia%22 (accessed 30 July 2011).

- ^ The Origins of Camera Phones: http://www.puremobile.com/cameraphones.asp (accessed 31 July 2011).

- ^ See for instance ‘Julian Assange Rapping!’ Rap News, Hugo Farrant and Giordano Nanni: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xa7I77F_DzA (accessed 31 July 2011).

- ^ Hans Ulrich Obrist ‘In Conversation with Julian Assange, Part II’, e-flux, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/238 (accessed 31 July 2011).