Walking into the exhibition Vernacular Cultures and Contemporary Art: from Australia, India and the Philippines I was immediately struck by a sort of contagious exuberant energy. If there’s such a thing as an Asian-Pacific-Australian zeitgeist then this exhibition could act as its guide. The exhibition was part of La Trobe’s lively international Word Image Action: A Festival of Ideas on popular print & visual cultures.

Vernacular Cultures featured recent art from the Philippines, India and Australia that engaged with both vernacular and global culture, a sort of global pop art for the 21st century. I use the term “pop” glibly here, yet, “pop” is never mentioned by the curator Ryan Johnston — and it is easy to see why. Pop Art has a specificity of time and place. It immediately places you in the centre. It conjures New York City, Andy Warhol. The term vernacular, on the other hand, has a completely different history and is able to frame the artwork within its own terms. As Johnston notes “Vernacular is used in acknowledgement of the term’s historically pejorative designation of ‘unofficial’ culture, a history that can be traced back through several millennia of colonialism and imperialism ... ”

Johnston places the exhibition as “distant conversations” grouped loosely around three themes. The first is “urban and architectural vernaculars.”

Mark Salvatus’ Hacienda (2009) is a garish green print of tiny cartoon-style figures in a fastidious farm. This cute country scene actually refers to a massacre of workers at the Hacienda Luisita, a large sugar plantation in the Philippines. Thus its cuteness belies a local history of corruption, greed and exploitation.

After Some Time (2008) a series of prints by Ken Botnick and Diana Guerrero Maciá delights in the found signs and colloquial expressions that the artists came upon while travelling in India. The handprinted text, with its charming imperfections, seems to match the local idiosyncratic signage while refreshing our blunted digital sensibilities.

Dominus Aerius elegance -6 (2008) is the work of two artists, Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra. This exuberant painting depicts apartment buildings floating peacefully in space as if bursting out of flowers — or have flowers burst into bloom underneath and carried them away? Up close you can enjoy the intricate detail of each building — from afar they proffer a sense of the magical and fantastical.

Johnston’s second theme is “cultural identity”, it is taken up with some force by Fiona Foley’s two complex photographs from the series Nulla 4 eva (2009) — the title a clever play on “Cronulla” and “terra nullius”. In one, a young Aboriginal man is standing and looking intently down the beach, his right hand raised to shade his eyes, the image is ambiguous and suggestive. Is he looking back or is he trying to see something or someone in the distance? This was to me an image of enormous generosity.

An old TV sits in a corner of the gallery as if in a living room playing Hoang Tran Nguyen’s Like a Version (2009). It features a karaoke style music video — but with a twist. Scenes from suburban Australia are intercut with ripped scenes from the 1980s Australian soap Neighbours as well as old martial arts films. The karaoke subtitles are also intercut with lines from Vietnamese refugees talking about their life after coming to Australia. Madonna’s lyrics now a cry of relief “I made it through the wilderness”. Yet I felt a sense of melancholy wistfulness.

The shadow play of Sangeeta Sandrasegar’s White picket fences in the clear light of day cast black lines (2009) is subtle yet dramatic and ominous, even beautiful, filling the room with mysterious presences and fleeting memories. The 15 laser cut acrylic figures are based on traditional iconography as well as images taken from online media of the protest march against violence in Australia towards Indians.

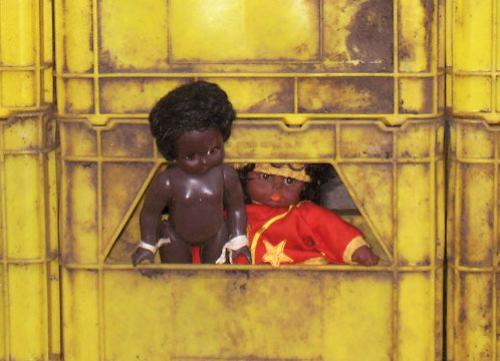

Finally, but most importantly in delineating the gallery’s space for this rich, diverse and unexpected exhibition, Maria Cruz’s protest fence cuts across the gallery space mute, yet graphically explicit, TV Moore’s remarkable The Forgotten Man is a surprise, while Scott Redford’s glamorous yet kitsch motel signage elevates the mood.