Report on Remembering Forward Forum, Cologne

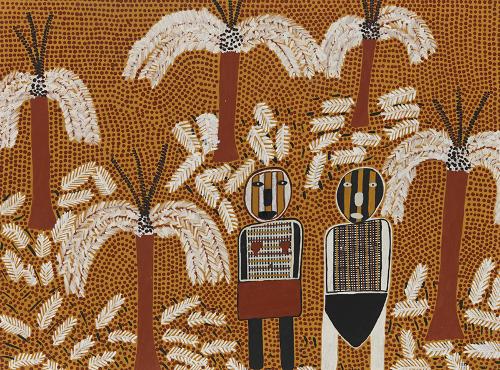

The richly evocative abstract paintings selected for Remembering Forward seemed to have been made for the Museum Ludwig's generous white walls, as if formalism had found its home in the Australian desert. I have never seen so much air between paintings in Australia, except in the display of the most revered European art at the National Gallery of Victoria. More than once Kasper König, Director of Cologne’s Museum Ludwig, extolled this very traditional curatorial approach. Was he being ironical, or was he suggesting that this conventional way of displaying fine art, and especially the finest abstract art, was the obvious way to go with these Western Desert paintings?

One thing is certain: the hang was a very strong statement about their status as fine art as opposed to anthropological object, especially given the location of the exhibition in one of Germany’s major museums of contemporary art. Thus the exhibition was a brilliant framing event for the symposium, which overall asked: "What does it mean to display Aboriginal art in a modern European museum?" It also made amends for Cologne’s infamous refusal of Aboriginal art in the mid-1990s. As the title of the exhibition implies, moving forward requires a settling of debts, and this was never far from the minds of those participating in the symposium.

However, König was keen to emphasise that he was not out to settle anything. He was not making amends for the city’s earlier refusal but capitalising on its scandal. All contemporary art worth its salt is unsettling, and it was this avant-gardist context that motivated König’s interest in doing the exhibition. The real political import of Indigenous art, he also said, is not land rights but, like all avant-garde art, human rights.

This goes some way towards explaining his very traditional hang. He wanted no one to be in doubt that this art, which in Europe is normally seen in ethnographic contexts, has all the aesthetic and critical power of the best European contemporary art. Some artworld types might get their noses out of joint, but König saw few risks. In his opinion the general public don’t care if art museums show ethnographic work.

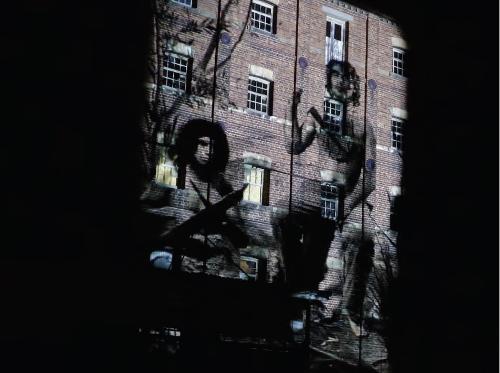

While the exhibition received good press, attendance was disappointing. Local artists and critics were also conspicuously absent despite the exhibition and the seminar being pitched in contemporary art terms. Meanwhile, across town at the newly opened Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Cologne’s answer to Paris’s Quai Branly, business was booming. As Alexandra Karentzos lamented, a new postmodern theatre of the primitive is how the public, including the new immigrant Europeans, want to view non-European art. Its dramatic lighting and dark interiors certainly have a sensuous pitch that cannot be matched by the Enlightenment rigours of the white cube so evident in the elegant hang of Remembering Forward. And at this latest of ethnographic museums, a special exhibition of contemporary African art was on view.

Nevertheless, well over 100 people attended the two day seminar. Again the local art world did not come but specialists from across Europe did. Further, the audience was very engaged, as they have been with the exhibition. Participants included a number of legends in the field: there was Jean-Hubert Martin, who organised the groundbreaking Magiciens de la Terre exhibition in 1989; Bernhard Lüthi, who was a curator on Magiciens de la Terre and the sensational Aratjara: art of the First Australians a few years later; the anthropologists Howard Morphy and Fred Myers, who since the 1970s have been extraordinary commentators on Yolngu and Pintupi art respectively;, and Terry Smith, the first art historian to be alert to the contemporaneity of Papunya Tula painting and a leading theorist of contemporary art. Two legendary indigenous curators participated, Franchesca Cubillo and Margo Neale (the latter virtually), as well as eminent European and Australian scholars working in the fields of Indigenous, postcolonial and world art studies. All that was missing were some Indigenous artists (though we were told that this was not through lack of trying on the organisers’ part).

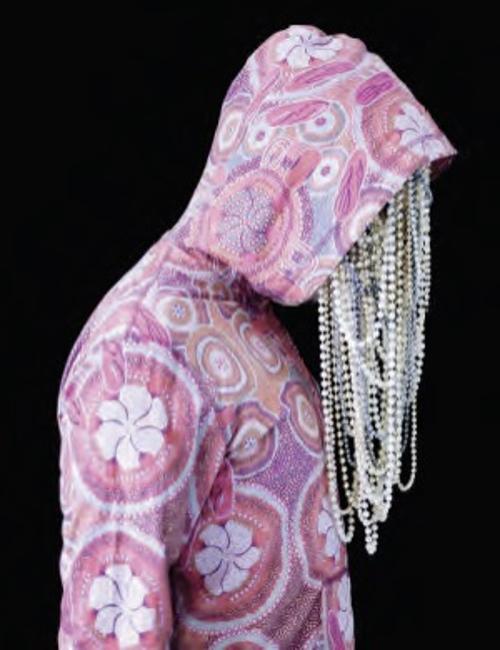

Myers introduced the term that became the buzzword of the seminar: 'unsettled’. There was the ‘unsettled’ discourse of Aboriginal art, the ‘unsettled’ nature of Aboriginal art, the ‘unsettled’ space of the contemporary art museum and finally the ‘unsettling’ of globalisation and the contemporary artworld.

A major factor behind this ‘unsettling’ that quickly emerged on the first day was the legacy of the divergent discourses of art and anthropology and how it has framed the production and reception of Aboriginal contemporary art. As König acknowledged, in many respects Remembering Forward is heir to Aratjara, which opened just up the road at Düsseldorf nearly 20 years ago. It was the first exhibition of Aboriginal art to tour Europe and North America within a militantly contemporary art frame - the first symptom of this being a minimum of labels – and to break the pattern of Aboriginal art exhibitions being curated by anthropologists.

Remembering Forward is smaller and more tightly curated but like Aratjara it retained retained a focus on indigenous voices and activist contexts. The catalogue included essays by the radical Aboriginal raconteur of the moment, Richard Bell, and theat blast from the past but ever present incendiary, curator and writer Djon Mundine.

However,, against the grain of Aratjara was the participation of anthropologists in this seminar. Anthropologists never backed away from the flak they received in the 1980s from Aboriginal activists and elements in the artworld. Morphy laid down the gauntlet in his opening keynote. His close iconographic analyses of several Yolngu bark paintings revealed their depth of meaning and nuanced hermeneutics, implicitly raising the stakes of this art from ethnography to high art. Further, in comparing several very different looking paintings that had the same story, Morphy also raised issues of formal invention. In this age of new art history his methodology reminded art historians of the roots of their discipline, thus challenging them at their own game.

Whether it was by accident or design, the debate between anthropology and art was built into the structure of the first day, with anthropologists and cultural historians speaking in the morning – much to the agitation of Lüthi (with whom I happened to be sitting) – and art historians and curators speaking in the afternoon. Aboriginal art may have, as Friederike Krishnabhakdi-Vasilakis put it, come out of the glass cabinet and onto the white walls, but in what ways and to what effects? This was a question at the heart of the seminar and the exhibition.

The question is vexed because of the cultural ideology of colonialism that is embedded in European discourses of art and anthropology. The once Manichean relationship between art and anthropology crafted and sustained European hegemony because it separated European and non-European art into a structural opposition of modernism versus primitivism, art museum versus ethnography museum. The dark chaos of the ethnographic museum was the dustbin of history, whereas the white modern cube of the fine art museum was the stairway to heaven. No wonder that in the 1970s urban-based Aboriginal activists determined that the best strategy was to get Aboriginal art into the contemporary art museum.

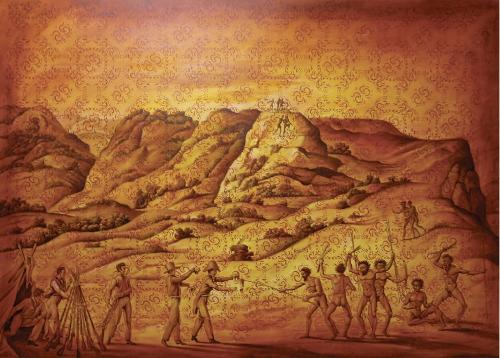

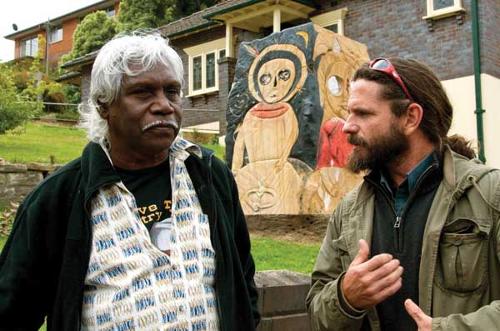

It was a timely move welcomed by some key players in the contemporary artworld. The Australian curators of contemporary art, Bernice Murphy and Nick Waterlow, pioneered this radical curatorial shift in the 1980s, and Martin and Lüthi pushed it into the European sphere – the latter with the help of Aboriginal activists Chicka Dixon and Gary Foley (and Djon Mundine). In this politicised climate artists such as Trevor Nickolls, Gordon Bennett and Tracey Moffatt even repudiated the term ‘Aboriginal’ and its attendant politics because it was too closely associated with the anthropological paradigm and so thus antithetical to their aim of being contemporary artists. Richard Bell and Vernon Ah Kee continue the crusade today in their attacks on Western Desert painting as being too anthropological, or as Bell says, too much Oooga Bbooga (superstitionsuperstition) and not enough of the contemporary.

However the choice between art and anthropology was always a colonial construct. One hundred years ago the European avant-garde art and some anthropologists began to dissolve this structural opposition. Wilfried van Damme argued that at least one German anthropologist Ernst Grosse made such a move in the late nineteenth century in his aesthetic appreciation of Aboriginal art.

In the post-Duchampian climate that took hold after World War Two, the neo-avant-garde artists began incorporating ideas from moved directly into the social sciences (sociology and anthropology) into their aesthetic strategies. This move was largely responsible for the discovery of an affinity with Aboriginal art by a new generation of artists (and like-minded curators) to claim Aboriginal art as contemporary art. At the same time a new generation of anthropologists were also moving Aboriginal art towards contemporary art – evident in the Dreamings exhibition of 1988, which, as Peter Sutton wrote in the catalogue, broke with the normal anthropological approach to emphasisze aesthetic issues. Thus the strategy of disavowing anthropology for contemporary art was, by the 1980s, somewhat passé. Yet it was necessary. And like a chronic disease that resists all treatment, it remains an issue.

The question of how to display Aboriginal art, as Cubillo made clear in her paper (which outlined the post-contact history of Aboriginal art and how this is reflected in the new hang at the NGA (National Gallery of Australia)) remains contentious and is not easily resolved. This is because these two discourses, once so differentiated, are now so entangled – even at an institutional level. For example, Cubillo, newly the curator of Aboriginal art at the NGA, is trained as an anthropologist, and Neale has a background in the artworld but is a curator at the National Museum of Australia.

Did the seminar offer any light on these unsettling entanglements that have characterized both neo-avant-garde and Aboriginal art? Did the seminar offer any light on this unsettling confusion? One attempt was made by the second day Georges Petitjean, curator at AAMU (Museum of Contemporary Aboriginal art, Utrecht), who talked about his recent exhibition Nomads in Art that considered the work of the Belgian conceptual artist Marcel Broodthaers in the light of the conceptualists of the Australian Desert.

His current subsequent exhibition Breaking with tradition: CoBrA and Aboriginal art develops developed a narrative (part fiction part fact) between the mid-twentieth century CoBrA artists, the Melbourne Roar group and Western Desert painting. Here was something most interesting and different to the usual exhibition of Aboriginal art seen in Australia. (See article by Khadija La this issue Artlink, p. ?.) Petitjean has no answers to the ‘unsettled’ discourse of Aboriginal art – indeed he brushes it aside – but he points to alternative and perhaps sunnier routes that reflect a whole new terrain opening in the wake of globalisation.

This was the subject of Smith’s paper. According to him, in the contemporary world the categories with which we once understood art are dissolving. This had been the radical intuition of Martin, Lüthi and Mundine 20 years ago, and the main impetus for König to develop the Remembering Forward exhibition and seminar.

I only hope that it is not another twenty years before another such exhibition and seminar is organised in Europe, as I came away with the unexpected sense that it is a better place to think about Indigenous art than Australia. Perhaps the legacy of colonialism is not so urgent in Europe. Strangely (for someone who grew up being taught that Australia was a very modern place that lacked traditions), tradition now seems more of a burden for Australians than Europeans, and so in Europe there seem more possibilities for Aboriginal art. In Australia we are preoccupied with the question of how Aboriginal art fits into the Australian art story when we should be thinking about both in terms of the world.

(Exhibiting Aboriginal art was a symposium organised by the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 17 and 18 February, 2011, in cooperation with the Institute of Art History of the University of Basel, as part of the exhibition Remembering Forward. Kasper König, Claus Volkenandt, Emily Evans and Frank Wolf organized the symposium. This article is based on closing remarks I gave at the seminar.)