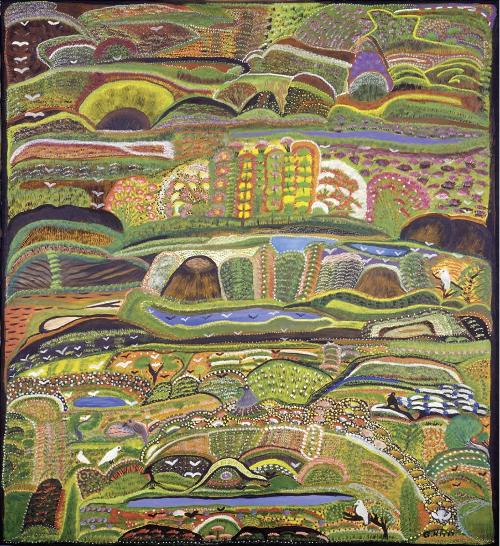

I often think of the natural environment of the continent as a metaphor that mirrors the history of colonisation; a kind of infinite pathetic fallacy redoubling on itself. It’s a contemporary phenomenon as much as a historical one. The relationship between Indigenous people and colonial settler society, and indeed the modern Australian state, is shaped by where we live. Unsatisfactorily, Aboriginal art is still defined geographically - as either urban or remote; even though Brenda Croft wittily suggested in 2003 that ‘there is no such place as Urbania’. Those trapped in the urban grid are said to possess no cultural authority, to be inauthentic. In the remote context, Aboriginal people are said to be part of the natural order of things; indeed, in the colonial mind we were imagined to be an aspect of the natural environment, like flora and fauna. Guerilla resistance fighters like Pemulwuy or the magical Jandamarra were said to be at one with the landscape and to appear and disappear like ghosts under the protective cover of the bush. But many of us are now estranged from our countries. Driven off and resettled, scattered in a great internal diaspora, many Aboriginal people have lived for generations on the country of another nation, another clan. Many of us voluntarily choose to live elsewhere. But even if we do, in the urban context we are strangers in another country.

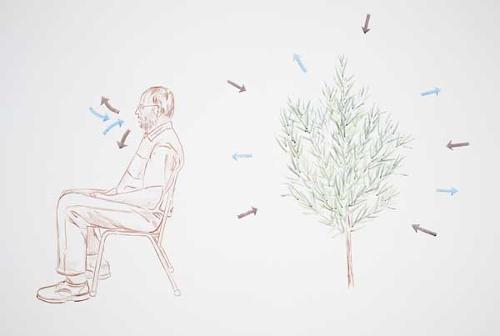

Just as Australia’s natural environment, often described as the driest and harshest in the world, was the crucible of generations of Aboriginal people, it also frustrated and complicated the rather straightforward yet brutal motives of British imperial power. Barren and inhospitable, the natural environment of the Australian continent was the antithesis of the fertile but overcrowded British Isles. A strange but compelling duality emerges in this early phase of colonial history. The newcomers experience both the beauty and terror of the land.

I love her far horizons,

I love her jewel-sea,

Her beauty and her terror,

The wide brown land for me.

Dorothea Mackellar’s nationalist ode – most recently cited in the aftermath of the Queensland floods by the Prince of Wales – expresses a kind of poetic and sentimental awe, yet it also speaks to the unease, the sense that ‘out there’ lurk wild, untamed and uncontrollable forces. The seminal film Walkabout (1971) preys superbly on this kind of primal fear in the white Australian psyche; of abandonment, and of being swallowed up by the country, of inexorably going native. Rarely do we confront the beauty or the terror, whether it is real or imagined, historical or contemporary. Yet Aboriginal art – that is, art that is made by Aboriginal people – takes us right to the heart of the duality, if we care to see.

It was the writer and activist Kevin Gilbert who described the colonial project in Australia as a profound rape of the soul – a violation so profound that generations of Aboriginal people would wear the stain, we will not forget. As racism morphs and takes on pernicious new forms, social justice – a job, an education, freedom from racism itself – is still beyond the reach of many Aboriginal people, as is the long frustrated hope for land justice.

In recently tabling the third annual report of the Close the Gap policy initiative, the Prime Minister Julia Gillard issued a generalised call for Aboriginal people to take care of their children, pay their rent, save up for a home, respect social norms and the rule of law and most strangely, to ‘reach out’ to other Australians. That is, be more like us, assimilate. In a simple but effective rhetorical manoeuvre, she once again foisted the blame for the tragic gap in life expectancy on to Aboriginal people.

As compassion fatigue sets in and as political activism dries up or is pushed to the margins by a sinister form of passive racism, the fight for cultural and social rights, for recognition, is being taken to the white cube and the big screen, the new fronts in the wars of representation.

But let’s not forget that the gallery space is a mirror, not a fourth dimension. And the fight there is no less entrenched, no less real.