How long can the majority wait for their story to unfold

They took their life and liberty friend but

they could not buy their soul

Kev Carmody

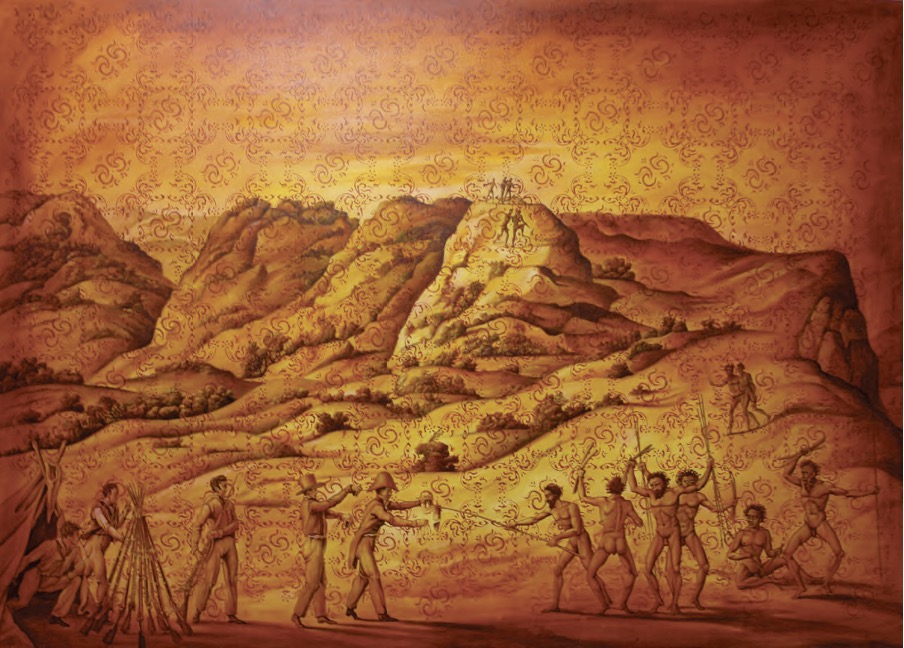

Indigenous music is flying high, Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu is on the cover of Rolling Stone, the recent Byron Bay Blues Festival included him, Saltwater Band, the Stiff Gins AND Bob Dylan. At the 2011 BigPond Adelaide Film Festival Indigenous art and film were quietly but spectacularly on the front page with premieres of features Mad Bastards and Here I am ; documentaries The Tall Man and murundak: Songs of Freedom and exhibitions Stop(the)Gap, Tracey Moffat: Narratives and tall man by Vernon Ah Kee.

Stop(the)Gap, curated by Brenda Croft, included Warwick Thornton's commissioned work Stranded a 3-D moving image of himself on an illuminated glass crucifix rotating in the air above a remote Australian landscape (also reproduced on free limited edition boxes of popcorn). Based on Thornton’s drawing he did when he was six about his wish to be like Jesus, and evoking Noel Counihan’s linocut portrait of a crucified Albert Namatjira, it is a hard work to interpret. It seems to embrace a kitsch cliché image of Aboriginal suffering as well as showing it to be a somehow endless spectacle. Thornton’s Samson and Delilah, a film full of the authority of a gifted filmmaker as well as the grim reality of some Aboriginal lives won the Camera d’Or at Cannes in 2009 for best first film.

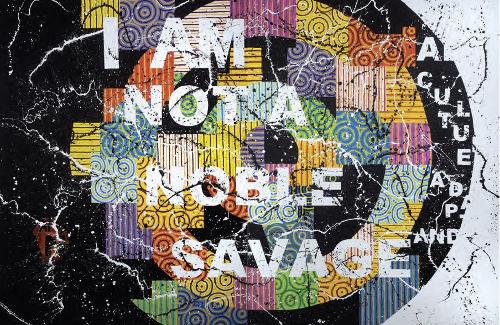

More and more Indigenous stories are being told by Indigenous people with Indigenous voices as well as in collaboration with non-Indigenous peoples. Stories of trouble? Yes. Stories of triumph? Yes.

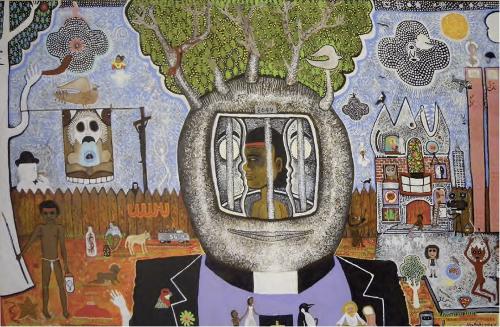

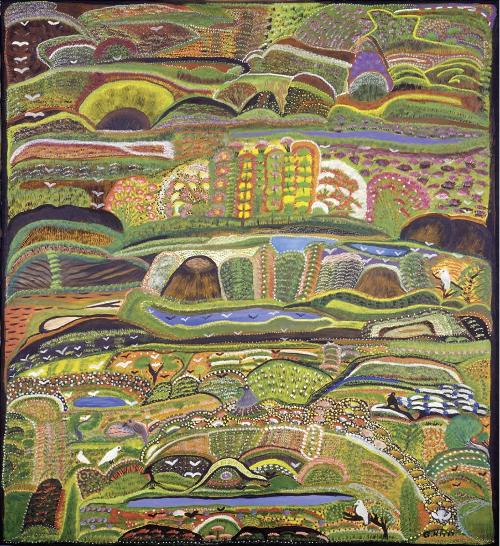

Indigenous culture is moving out of dedicated spaces and into the mainstream. Ultimately all Indigenous culture is claiming the space for experiences that have not been widely told and this broadens the space for the stories of everyone whose stories are untold. Powerful Indigenous art often comes from places and people that appear to be powerless. This is one reason it is strong, it has a necessity, an urgency about it. For all the irony in some work there is an authenticity factor that is incontrovertible and that may well be the high moral ground asserted by Thornton’s Stranded. Many years ago it was Papunya painter Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri who made the telling remark "the money belongs to the ancestors", that is to say the wealth of the culture provides for its people.

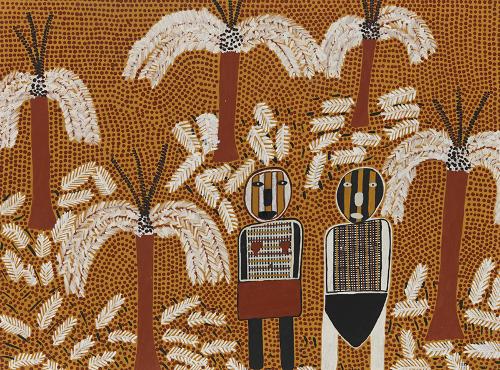

The art in this Artlink ranges from art made many years ago in the Torres Strait, in Tasmania, in Arnhem Land, in Queensland, in Western Australia to art being made today in Mackay, in Cairns, in Arnhem Land, in Elcho Island, in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and other places. The articles from writers all over Australia and the world deal with how to talk about the wide range of work, how to place it in history and in many cases how to rewrite history to incorporate different perspectives and diverse qualities both in Australia and increasingly in Europe.

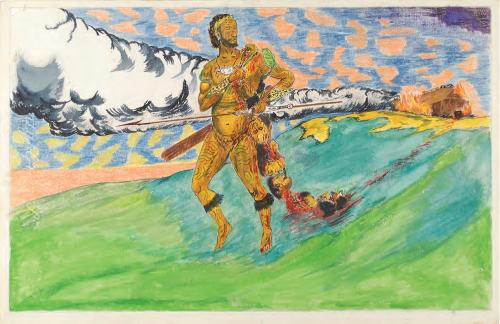

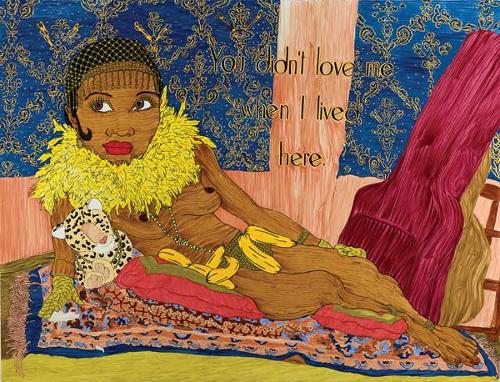

Art as education, art as bearer of information, wisdom and stories, of belonging, as statement of longevity in that place, art as celebration of home, of land, of courage, of tragedy, of connection, of stories that acknowledge the complexities and difficulties of life as well as its wonders and gifts. Art by trained and untrained artists, by iconoclasts, by people with passion and agendas.

Ernst Gombrich wrote in his book The Story of Art (1950), which features a photo of an Aboriginal artist painting a Possum Dreaming on a rock, that we must always remember that images precede writing, and thus implicitly that images are a kind of writing. Art is about politics and history but also empathy and communication. Art materials and art methods like painting, drawing and printmaking find new life in the hands of Indigenous artists with stories to tell.

Many articles in this Artlink speak of a dichotomy between art galleries and museums, between aesthetics and ethnography, between an idea of art as something disinterested and disengaged, and the study of culture as one culture’s examination of other cultures. Yet all stuff in museums has always had aesthetic dimensions and all stuff in galleries has always had ethnographic dimensions. You just have to rewrite the labels.

Art is never disinterested and disengaged, living cultures always exceed and overwhelm the boundaries placed around them. And this is what we are seeing in Australia and in this Artlink, a living culture.

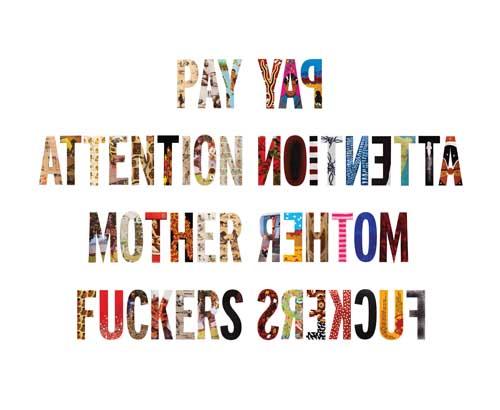

At the last Cairns Indigenous Art Fair Richard Bell spoke about his experience of New York and said that he noticed there that it was not the black man who was at the bottom of the pecking order but women. Bell was going to create A Blackfella’s Guide to New York City for Artlink but it didn’t happen. Maybe next time.

Last year Artlink celebrated its thirtieth birthday as a unique magazine covering contemporary art in Australia as a forum of ideas, acts of courage and commitment. This June 2011 issue Beauty and Terror is the fourth time Artlink has focused an entire issue on Australian Indigenous art but the first of a new series called Artlink Indigenous to be published each June as a bumper issue - more pages, more art, more words, more debates – focusing on a multifaceted art that is ever-evolving and has a deep history.