Listening to Tracey Moffatt in conversation with Art Gallery of South Australia Director Nick Mitzevich is not dissimilar to experiencing her photographic works: a jump-cut narrative that leaves her audience to make connections. "I can barely use a camera. It's all point and shoot" she says, once again providing only snippets of the story. “I don’t know about light. Ansel Adams means camping out to wait for the light.” Moffatt’s ironic and oblique reference to her elaborately constructed realities delights her audience but she speaks in ways that suggest more than disclose.

Recently returned from living in New York (“No giant loft...rats, rats, it’s terrifying”) she seems comfortable to be back in her home state of Queensland and working, not in a studio, but on her kitchen table. (“I’m still doing my homework.”) She seems ready to take a step back, to slip into the background where she will no doubt watch with clarity. “New York is the centre of the universe but now I don’t want the centre.” And when someone suggests that for young people the internet is the centre, Moffatt proves that she has lost none of her edge, “Bravo! Good! Yeah, but you are still in your own room. It’s safe!”

Tracey Moffatt: Narratives combined her groundbreaking films with three video montages (produced with film editor Gary Hillberg) and seven photographic series. The stylistically varied exhibition is a reminder that film and photography cross paths in Moffatt’s work. Her photographs never seem to exist in an isolated state - they suggest a sketchy, uncertain narrative content, or at least an intention. In contrast her films seem like a series of tableaux that are carried forward more by sound than story.

In many ways it is the indeterminacy of her photographic series, the obvious complexity of conception, which provides the incentive and rewards for engaging with Moffatt’s work. She is virtuosic in her visual range, from the lush artifice and saturated colour of Something More (1989), to the seemingly casual snapshots of Scarred for Life (1994) with text captions that casually reveal childhood scenes as traumatic memories. The highly theatrical Laudanum series (1999) pays homage to an eclectic collection of styles; disquietening Victorian interiors, expressionist film techniques, gothic fiction and erotica in ways that bring new energy to familiar visual conventions.

Tracey Moffatt previously worked in television, at SBS, and on music videos. She knows about cutting and pasting and perhaps more importantly she knows about pacing a story (“I am about pacing”). And so in this exhibition the narratives unfolded, both familiar and singular, leaving the viewer to decipher and make connections between race, class and gender, between realities and fantasies, from images that refuse resolution. And what’s next for Tracey Moffatt? “I’ve done with montage...I’m leaving the theft, the stealing of imagery behind... I might do something for television but it’s very hush hush!”

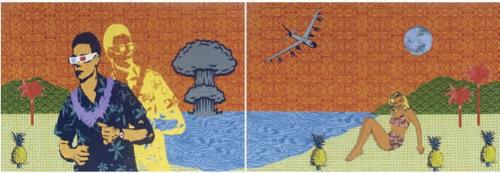

The same day that Tracey Moffatt spoke with such playful and practiced confidence, a very different conversation was unfolding at the Samstag Museum at a forum on another dynamic exhibition, Stop (the) Gap: International Indigenous art in motion. Chaired by Hetti Perkins, Indigenous artists and curators from Canada, America, New Zealand and Australia spoke quietly, with passion, as they sought to explore visual points of connection amid shared histories of dispossession, injustice, inequality and misrepresentation. One artist described the investigative project as “how the lens changes the way they think about us”.

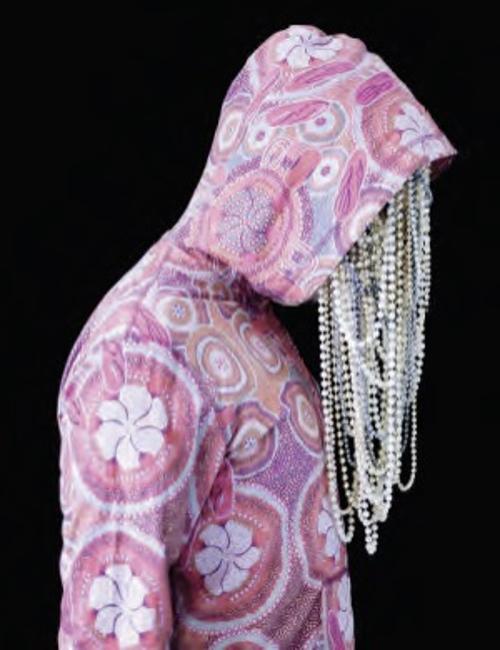

The exhibition is dynamic, fresh, spectacular and yet the poise of some works creates pockets of calm for contemplation. As New Zealand artist, Lisa Reihana, observed “Sometimes it is about the work and sometimes it’s what sits outside the frame.” Reihana’s Te Po O Matariki (2010) shows a traditional karanga to those who have lost their lives in battle. It is sung in exquisite silence. Whirimako Black’s sensual movements and fluttering fingertips call forth an apparition, the Tui, a bird, harbinger of souls. The silent singer’s traditional make-up, bare feet and elegant black dress speak to a new and contemporary representation of Maori women.

Canadian Dana Claxton draws on traditional Lakota ceremony to create a similarly powerful and meditative space. Claxton describes Rattle (2003) as a visual prayer “to create infinite...to bring spirit into the gallery space.” The quadraphonic visual and aural sequence of traditional beaded rattles shaken in real time and shown in slow motion is mesmerising. New York-based Alan Michelson’s work powerfully addresses place, memory and the North American landscape in a profound and poetic multimedia installation. TwoRow II (2005) follows the banks of the Grand River simultaneously showing the Six Nations Reserve on one side and the non-Native townships on the other. In the sound track, voices of Six Nation elders compete with the voice of a non-Native cruise captain each describing the same geography.

Stranded is the first time Australian film-maker Warwick Thornton’s has created a work for an art gallery. He has filmed himself as a Christ-like figure on a cross, floating, revolving above a waterhole in the brilliant, harsh light of a remote Australian landscape. The sounds of wide-open spaces – birds, a blowfly, a windmill turning – reinforce the tension of imagery. The depiction of 'black Jesus’ is not new but the technical expertise gives a visual power to this three-dimensional work (you wear the glasses) that is extraordinary.

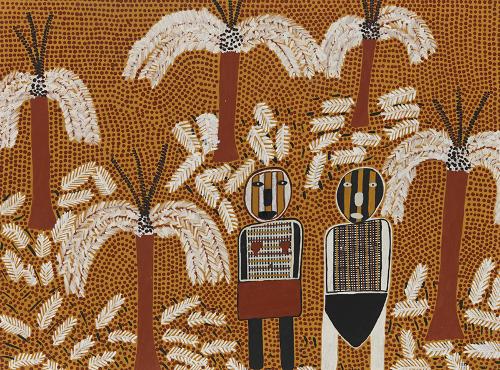

The satirical gesture of Warwick Thornton’s limited-edition cup of popcorn – FREE! – adorned with a still from his work, links comfortably with Tracey Moffatt’s play with representation and the ironic layering of shifting meanings. However, most works in Stop (the) Gap give primacy to visual, historical, biological and geographical ‘evidence’ of Indigenous cultural identity in a way that runs counter to postmodernism’s distrust of representation. If there is a common thread running through this contemporary Indigenous art, it is the uncompromising exploration of what it means to be human in a (post)colonial age, combining the timeless and the contemporary in work that repays repeated engagement.

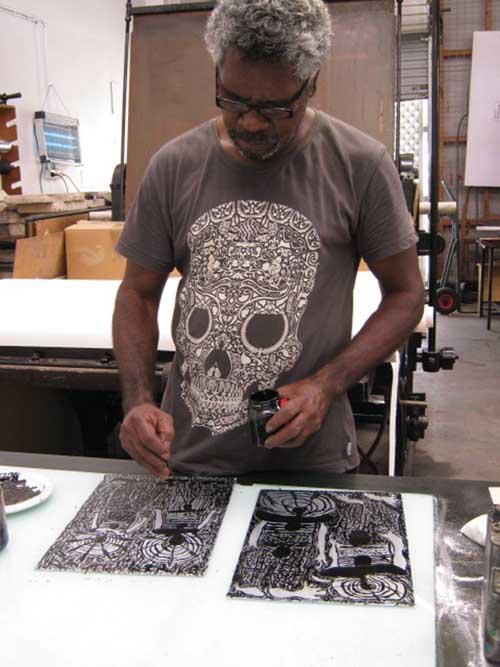

Vernon Ah Kee’s tall man is Lex Wotton, a local Aboriginal man who spoke on behalf of the grieving and angry people of Palm Island when Cameron Doomadgee’s death was declared ‘an accident’. While there has been extensive media focus on Chris Hurley and allegations of police corruption, there has been very little said about Lex Wotton’s seven-year jail sentence for inciting a riot nor the current court order (a condition of Wotton’s release) that prevents him from speaking to the media or public groups.

Ah Kee, whose cousin is married to Lex Wotton, recognised that as an artist there were things that he could show and say that others could not. His work tall man is a testimony to the power and importance of art in presenting another way of seeing and experiencing very public events. And tall man is a compelling work of art. The four-channel video installation shows hand-held moving images taken by people there on the day. The sense of chaos, bewilderment and disbelief is tangible and moving. The images are disrupted, seemingly at random, by a test pattern used to adjust colour on screen. tall man confirms Ah Kee’s reputation as one of Australia’s most exciting and important contemporary artists.