The highly considered selection of twelve works (2001-2010) in John Barbour's partial retrospective "Work For Now" at the Australian Experimental Art Foundation included his now-trademark embroidered fabric works, sculptural objects, small freestanding, photographic-collage tableaux, as well as the 1990 painting “THINK”.

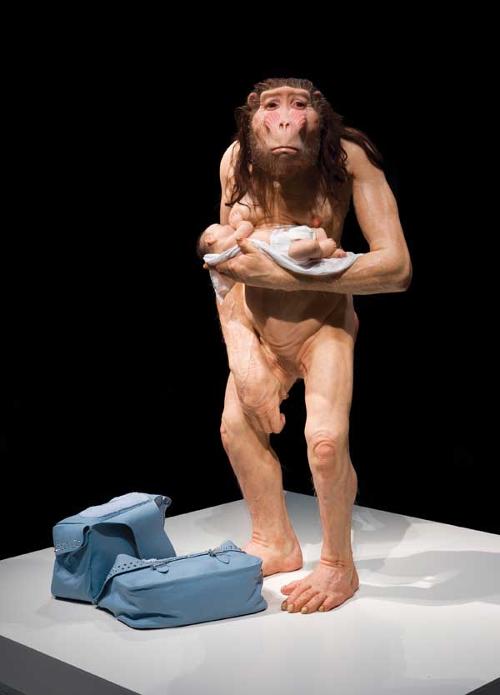

From the “I’m a happy little rabbit” vignette to a seated figure, whose head is a cloud and a stack of signs featuring the repeated entreaty 'help’, the Chemical Islands (2003-2010) series of small-scale, photographic-collage works appeared to speak of the uncertainty of contemporary existence. A male figure hesitates before an abandoned wooden crutch and a curtained proscenium arch, which is inscribed “one stick no drum”. Barbour has also cast himself in these tableaux - clad in eighteenth century costume next to a reclining nude, an ape and a door that opens onto a bricked-up ‘exit’. Another work in the series is an agglomeration of signage nailed to a wooden cross, in which each sign is crudely labelled Untitled Object. The uppermost sign reads: “Another untitled fucking object”. Yet, one of the twelve works in “Work For Now” (despite Barbour’s customary imaginative facility with titles) is in fact called “Untitled Object”. Paradoxes of this kind – generally allied to wry humour – are integral to his oeuvre; in “No More Holes” (2008) the form of the wall-hung letters (shaped from lead) clearly contradicts the work’s title. Like the ‘abstract’, black and white painting THINK, in which the precise, hard-edge geometry spells out the word “think”, the content is staging an insurrection.

From an extensive archive of Barbour’s banners (first exhibited in 2001), Kerry Crowley has selected five representative, but distinctly differentiated fabric works. Polluting the apparent formalism of “My Brother Pink ‘s” (2006) dual, pink silk monochromes, Barbour has applied a gauzy patch (a form of bandaging) to mask what appears to be a blood stain; on its counterpart, a heart-shaped patch echoes the leaden heart in the first room of the gallery.

Consistent with his stated proclivity for dualism, Barbour, who is drawn to processes and materials that are “fragile, delicate and subtle – reflecting states of mind and moods that are ephemeral and transient” – is also attracted to working with metal “because it is hard and resistant and unforgiving”. Like copper (the mirror of Venus) and silk, lead is invested with rich historical associations, but it is not difficult to discern the additional appeal for Barbour of its dichotomous properties. Certainly one of the satisfying aspects of this thoughtfully staged exhibition was not only the alignment of soft fabric with the rigidity (or alternatively the seductive gleam) of metal objects, but the many correlations (formal and otherwise) between individual works. Thus “Where the Words Go” (2005) was positioned adjacent to the scrunched, copper-sheeting ‘paper’ and ‘waste-paper basket’, of “Dead Litter” (2008) which in turn chimed with the crumpled silk organza of the 2006 work “Close My Eyes” (strangled organza is the term given to this fabric).

Barbour’s materials have been described as humble and throwaway, yet they are frequently – in particular the silk components – of a relatively luxurious kind. Moreover, he has elected to use fine, diaphanous cotton voile, which has the capacity to flutter (banner-like) on the wall when suspended. Edges of the fabric works are customarily raw and fraying; surfaces are stained (Frankenthaler-like) and crumpled; embroidered text or imagery is scribbled and apparently unstable. (Barbour alludes to his needlework as “a looping calligraphic line”, but the occasional perfectly embroidered flower or letter reveals a level of technical competence that is elsewhere renounced.) Is it therefore more accurate to suggest that his fabric fragments are couched within an “arte povera” framework that constitutes an ‘unmaking’ of pristine materials – contrary to the inclination in contemporary art towards an elevation of the mundane? (Barbour has referred to his Bataille-related notion of ‘unmaking’ as both an “acknowledgment of mortality and ...a muted politics of resistance”.)

Absent from the prevailing sense of vulnerability evoked by this careful selection of works, were some of the artist’s more aggressive curses or proclamations, such as “I am War” from his 2002 exhibition Joy. Interwoven with humour and pathos, “Work for Now” presented the viewer with a (sometimes absurd) theatre of propositions, in which Barbour’s image of the dunce was never very far away.

In 2011 the Australian Experimental Art Foundation will launch a publication on John Barbour’s work, with essays by Teri Hoskin, Ewen McDonald, Michael Newall, Ian North, Russell Smith and Linda Marie Walker.