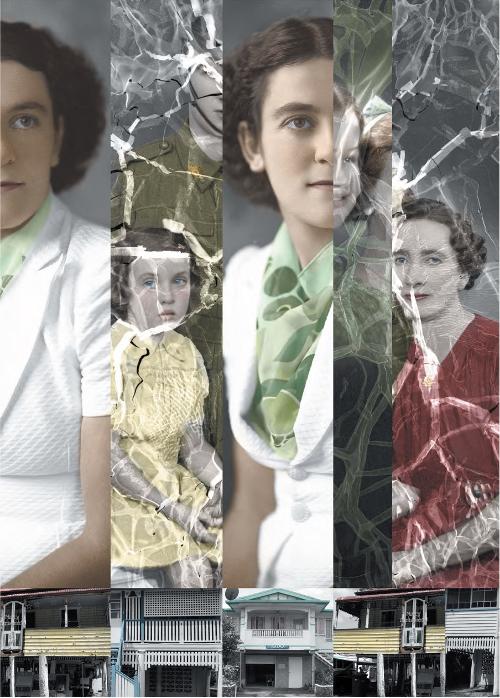

There is something both cloying and utterly sadistic about Magda Matwiejew's most recent body of work. But simultaneously it is seductive, beguiling, sensual and downright sexy. It is a morass of contradictions; we are forced into both awe at the grace and elegance of the human body, and repulsion as we consider the almost literal sado-masochistic tendencies at play.

With a delicate palette of pinks and flesh tones, this is very much a 'feminine’ body of work. But, perhaps inevitably, with femininity comes contradiction. Appearance, regardless of pain or practicality, is inevitably a prerequisite in Western notions of being attractive. But similarly, achievement in almost all physical artforms and sports, also comes with questions of pain and practicality. Australian Rules footballers risk long-term bone, brain and muscle ailments for their moment of glory, Sumo wrestlers sacrifice longevity for bulk in order to succeed, and ballet dancers, as Hans Christian Andersen’s 'The Red Shoes' so grotesquely reminds us, live in agony for their art.

Matwiejew’s 'En Pointe' entailed both a film projection - titled 'Pretty Ballerina' – and twelve digital prints. A re-envisaging of Swan Lake, Matwiejew’s rendering roils from sublime beauty to the sickening reality of self-imposed torture in the bid for that very sublime. She evokes the inherent eroticism of the female dancer; the lithe body, the self-assurance. In 'le miroir' a dancer stares into a mirror with barely disguised arrogance, in 'orchidee' the dancer is topless, her back to the camera, head thrown back with a lascivious, come-hither smile. The pink of a giant orchid as backdrop melds with the delicate pale skin of her torso set off by the colour scheme of a bordello; flaming red shoes, crimson underwear and a mane of unruly red hair complete the scene,

As with a number of artists who work in video, Matwiejew relies on a series of stills for her installation. This can be problematic for some artists, where the translation from moving to still image leads to clunky stills that fall short out of a cinematic context. But Matwiejew has chosen her images with great care, each individual shot perfectly composed and balanced. Indeed, the narrative is almost more powerful in the 12 prints than in the video, allowing the viewer to contemplate the specifics of both seductive beauty and the agonizing pain behind it. At times this is overt – and these are in fact the most potent images – in 'chaines' the dancer’s long legs culminate in painfully shackled chained ankles. In 'chaussares de ballerine' the fallen dancer proffers a bruised foot, the victim of her art. 'Trois masques', which features three women blindfolded in red, could just as easily be a still from a soft-core sado-masochistic film à la Stanley Kubrick’s' Eyes Wide Shut.'

'Pretty Dancer' is as much Hans Christian Andersen’s gruesome fairy tale 'The Red Shoes' as it is 'Swan Lake';a meditation on vanity and its potentially grotesque ramifications.

For many years Matwiejew was best known as a painter before re-inventing her practice in the past six years, moving exclusively into digital media. She has been particularly recognised for her award-winning film 'Insect' (2007) and has exhibited widely internationally at various experimental film festivals. But it is her painting background that perhaps sets Matwiejew’s work apart from many working in the digital realm. Both in terms of composition and palette – in this particular case an extraordinary array of reds, pinks and flesh tones – her work is distinctly painterly.

However it is the digital that allows her such ease in juggling time and space. Matwiejew shifts from the baroque to the present with unnerving ease; transient clockfaces indicate shifts in temporality, as though Matwiejew were commentating on the never-ending battle between feminine vanity and its gruelling realities.

In 'chaussares de ballerine', as in Andersen’s 'The Red Shoes', the ballet slippers are finally discarded, but not without great cost. One is tempted to transpose this bruised and fallen body onto women who waste away from anorexia or suffer the humiliations of the knife in plastic surgery, only to have the most hideous of results.

Matwiejew’s latest work seems to fall into a general reassessment of the feminine form in contemporary Australian art. Monika Tichacek sewed her legs together, Jane Burton allows treeroots to envelop her bodies, Mimi Kelly’s self-portraits bleed profusely and Pat Brassington’s women are distorted mercilessly. Perhaps in the days of the post-post-human, when notions of the Feminist are being called into question, these artists are posing new debates about just what it is to be a woman.