Books. You remember books. Like webpages only you can hold them in your hands. In Artlink's 2009 'Changing Climates in Art Publishing' forums and edition Lisa Havilah, the canny director of Campbelltown Arts Centre and guest editor of Artlink’s upcoming issue on Diaspora, firmly declared that artists need catalogues and revealed that Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei agreed to have a major survey exhibition at Campbelltown (of all places) on the condition that a book surveying his work was published.

Artists need catalogues said Havilah and she may well have said artists need books. The saying (or is it an urban myth?) goes that when Australian artists go to Europe the first question they are asked is: where is your book? And everywhere European artists in their twenties have them.

A recent crop of Australian art books are monographs. The artists they deal with include Ingo Kleinert, Joachim Froese, Renata Buziak, John Davis, Khai Liew and Jutta Feddersen. Three of these six artists have a German heritage which is heavily emphasised in each book, Renata Buziak has a Polish heritage and Khai Liew a Malaysian one leaving only John Davis as a minority Anglo-Saxon Aussie.

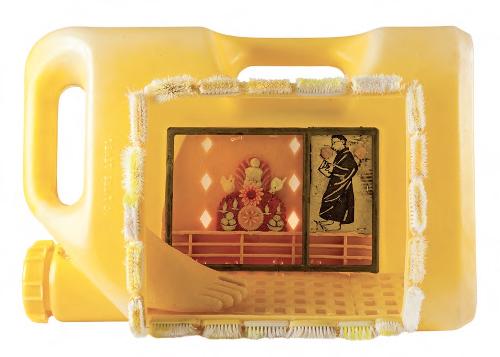

Australians are often people with a life, heritage and background based in other places and indeed that is a distinctive part of the richness of our contemporary art. In the case of Aboriginal art the emphasis on country is also an emphasis on identity and origin, location and traditions. 'Before Time today: reinventing tradition in Aurukun Aboriginal art' draws together collections of historical sculpture made at Aurukun that are held in museums in Queensland, Canberra and South Australia with a new collection of contemporary material held at the University of Queensland Art Museum. The book draws together texts by John Von Sturmer, Peter Sutton, Sally Butler, David F. Martin and Georges Petitjean. The latter, based at AAMU (Aboriginal Art Museum Utrecht) writes about the little known story that in 1606 the first Europeans who set foot on Australian soil, were Dutch sailors from the Duyfken (little dove), nine of whom were killed by Wik Aboriginal people. In 2007 the Wik people donated 12 ceremonial law poles to AAMU in a gesture of reconciliation.

In the highly informed and engaged words of anthropologists Von Sturmer and Sutton there is a distinctive cloudiness that covers and evades the truth that somehow the earlier Aurukun work has an aesthetic quality that is lacking in some of the later pieces. Was its making less rushed, was it more based on observation or experience? It was certainly intercultural in using woodworking tools and skills introduced by missionaries. The issue of how and who decides what is good in Aboriginal art comes to the fore. The other issue somewhat obscured though mentioned by Martin is the ongoing turbulent social unrest at Aurukun. Can art help the Aurukun community? Can art contribute to peace in a community? Where does quality control come in or is all indigenous art valuable? Can Aboriginal people be allowed the time to develop their work? This book is very valuable in sharing images of past and present works, a follow-on to the QAG exhibition 'Story Place: Indigenous Art of Cape York and the Rainforest' in 2003 it is hopefully a strong step on the path to a happy, productive and thoughtful future.

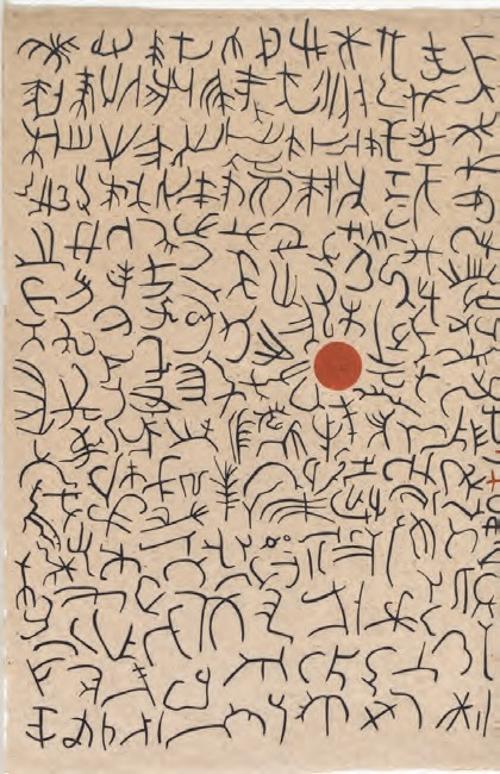

Vivienne Johnson’s book 'Once upon a time in Papunya' on the origins and history of the Papunya Tula painting movement is like a detective story. A 'myall’ is the Aboriginal word for a wild Aboriginal, one who lives traditionally, has come straight from the bush and is unsophisticated in the ways of non-indigenous Australians. The Pintupi who were the last Central Australian people to come in from the bush were myalls at Papunya and Johnson suggests that that is one reason that their art is so strong. Johnson herself is something of a myall in academia, which is not to say that she is not rigorous. Her first book, about which I heard her speak in the early eighties, was on Radio Birdman one of the first Australian punk rock bands. In fact the DIY aesthetic of the bush and Kaapa Tjampitjinpa’s old dusty suitjacket held together with safety pins reminded Johnson of Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols and that he insisted he was a musical anarchist but not a revolutionary. Kaapa, she says, was undoubtedly "an artistic revolutionary but was he [also] a cultural delinquent?" The tension in the book is whether some art made at Papunya, especially the early boards, was really meant to be made or seen. Most readers know that they can’t judge this, and what Johnson is talking about is still to be played out. Will the days of simply seeing an early Papunya board hanging in a gallery come to an end as they are packed away to only be shown to senior men? Is the art like any other art or does it need special treatment?

Johnson’s investigation of the origins and development, marketing and analysis of Papunya Tula art revolves around the true nature of its origins, whether and how much was happening before Geoffrey Bardon arrived and thus where the art came from and how it was decided what to paint and whether secret sacred material was included. In the case of the 2009 'Icons of the Desert' exhibition of early Papunya boards from the John and Barbara Wilkerson Collection shown in the USA in Los Angeles and New York a point was made of consulting the surviving artists or their relatives as a result of which certain works in the exhibition were then banned from being in the publication in Australia though they appear in the American edition. Johnson’s agenda which is implicit rather than stated openly is that this art is more than art, more than a commodity and its power is not dimmed. One of her motivations must surely be to write all her investigations down while some people who remember what happened are still around. A book of great depth it is also very laborious at times. The passionate story it tells is complex and at times hard to understand but that it was written is certainly A Good Thing.

It is debatable whether the style of the monograph has kept up with art history’s more recent concerns with context and deep time. A relatively relentless biographic approach is kept to in each of the volumes listed above dealing with individual artists though the book on John Davis who died in 1999 has a memoir by Robert Lindsay, a historical essay by Robert Hurlston and then Charles Green’s essay which, as might be expected from this rather sharp art historian, takes a broader look at Davis’ output and place in Australian art and mentions other artists and other places. This is the way that depth is found, not by pretending that an artist springs from nowhere or their own forehead but by showing the depth of their interconnectedness. The Davis book is exemplary in this regard though the images on the whole fail to convey the fragility and delicacy of his work, and I wonder how comprehensive it is. I recall seeing the impressive 'A hill, a river, two rocks and a presence' on Herring Island in 1997, a work that does not feature in the book.

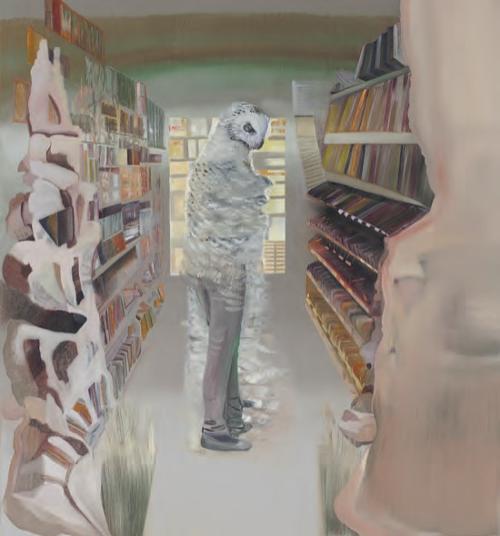

The lush book on Joachim Froese is a real coffee table book. In fact a lectern may be more suitable. An essay by Tim Morrell and an interview with Ian Friend both emphasise Froese’s German-ness perhaps excessively. Five series of work by Froese are reproduced. The work is highly professional, involves a clear crisp eye and possesses a deep sense of the fragmentary nature of experience. Insects, toys and books in colour and in black and white re-inhabit the zone of memory, the vividness of childhood and the intensity of seeing and therefore reflecting that photography can underline. This book is bi-bilingual and so is the book on Renata Buziak whose work was completely unknown to me but which is quite fascinating as she allows plants to decay, photographs them then digitally tweaks them and prints them very large. Victoria Garnons-Williams’ essay draws out the wonder of the work and emphasises the sense of Buziak’s work as a journey. Bravo. Both books are published by the Queensland Centre for Photography which began publishing one book a year of Queensland-based photographers in 2005 and so far has done Marian Drew, Ray Cook and Martin Smith. And has just now started to make smaller books on specific bodies of work of which Buziak’s book is the first.

'In Two Decades' the book on Ingo Kleinert’s work art historian Jenny McFarlane who rises to eloquent statements such as “The native derangement of the material is only held in check by the discipline of the assemblage.” mentions only two other artists Sidney Nolan and Lucio Fontana in relation to Kleinert’s work. The book is a fair and detailed outline of Kleinert’s work over the last twenty years. What the book does not do and which I find untenable is to not mention the work of Rosalie Gascoigne, not once. Both artists live or lived in the Canberra region, both use or used found materials including corrugated iron and often make or made grids. To not mention Gascoigne’s aesthetic as having some connection to Kleinert’s seems just plain silly or perhaps absurd. 'Two Decades' is published by SFA Press, curator and founding editor Merryn Gates’ new imprint publishing books on individual artists. Prices reveal the viability of a monograph for every artist, for the A5 at 80pp the cost is $5500, for the 21cm square at 80pp it is $8500. The books are printed in editions of 250. Apart from essays by McFarlane and Anne Virgo 'Two Decades' has a timeline in two columns placing quotations from reviews etc of Kleinert’s work alongside a chronology of exhibitions - this is very useful once you get the hang of it – the layout could be improved with headings to make these complementary listings work even better.

Jutta Feddersen’s book 'Substance of Shadows' for which her daughter was the graphic designer is a luxurious volume with more than one tiny book sewn inside it. The book is in two parts, the first half being biography and the second being art. The story of Feddersen’s life, an idyllic childhood in Germany followed by a very harsh eviction from that life, contains strong contrasts. Like Kleinert, though she was German she had to flee her home and how many people are really aware that it was not only the Jews who suffered during the war but also Germans when their country was liberated by the Russians and half of it became part of Eastern Europe under a communist regime. Feddersen’s tale is unedited and told without breaks or headings as a breathless monologue. An artist’s memoir rather than a rigorous monograph it is very personal and sometimes repetitive, a book for her children and friends more than for history.

The book on Khai Liew’s furniture by journalist Peter Ward is efficient and full of very restrained images of the deeply restrained work of Liew which often has complicated genealogies which are described here. In a simple cupboard or chair are embedded histories and memories – a piece of folded linen seen in a market in Paris, the woodcutters or tiersmen of the Adelaide Hills – that you would never suspect by looking at them. It is an elegant addition to the Wakefield Press library of books on South Australian artists and craftspeople.

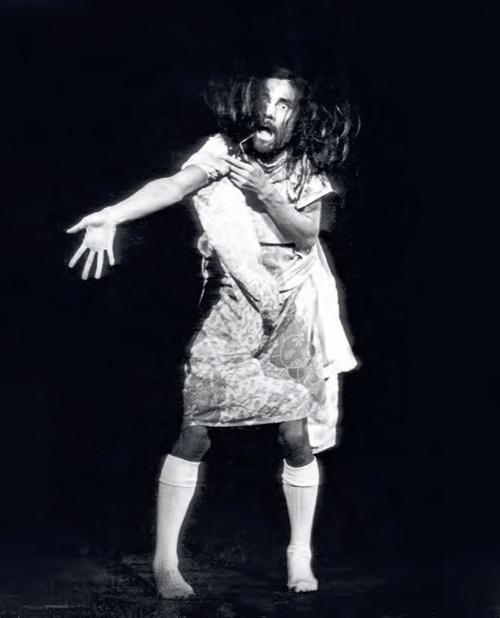

The book 'Rounds' emanating from PICA is a book to read slowly over a long time, a most impressive volume focusing on a project involving nine emerging artists and a kind of Chinese whispers process where in four rounds each artist makes something and passes it on to the next one. The book includes interviews, artist statements, eight writers, lots of images and as it discusses the development of work would be excellent for art school students and their lecturers. Best of all it is funny including all kinds of stories and snippets of information that hold out all the possible warmth and richness, contradictions and adventures of art practice, and indeed life. An example – part of George Egerton-Warburton’s name was derived from that of a saint whose most notable miracle involved resuscitating a goose.

A new category of post-computer books is the ‘hard drive book’ of which Annette Stewart’s 'Barbara Hanrahan' and Ken Bolton’s 'art Writing' are perhaps examples. This is of course where the writer has all this stuff on their hard drive and wants to get it into hard copy rather than see it consigned to technological oblivion or the trash bin. It has been collected, it has been written, surely it has value.

Annette Stewart is the author of another book about the work of Barbara Hanrahan published in 1998. Her new book is a blow by blow, dream by dream, account of Hanrahan’s life without adding the extenuating circumstances of why we should be interested in her now. Or so it seemed to me.

In Ken Bolton’s case twenty years of occasional art writing and reviewing while holding down a job running the bookshop at the EAF as well as writing poetry has come together in a very casual form that makes it fairly difficult to use. On the cover with its 1986 image of Bolton taken by William Yang, the words ‘Writing’ and ‘Ken Bolton’ are in big black letters, the word ‘art’ is small in white on yellow and even smaller in white and practically invisible is ‘Art in Adelaide in the 1990s and 2000s’. There is no title page.

Bolton says several times in the book that making visual art is very different from making writing. Of course many poets like Apollinaire, Baudelaire and Peter Shjeldahl have written about art (the last hilariously saying goodbye to the profession of art critic in a long poem, and then taking it up again). The best piece in the book is when Bolton writes about Rainer Maria Rilke and describes his work in relation to the work of Warren Vance whose work I cannot imagine from what Bolton writes though it is A Very Good Piece About Rilke. Clearly Bolton is better at writing about writing than he is about art.

The biggest problem with the book is that it is missing clear information such as dates and places of the exhibitions discussed and the whereabouts of the publication of the pieces of writing that might have made it useful. On occasion a few comments on an artist are placed together but it is only through reading them that it is possible to try to make out which comes first. Thus putatively presented as history the book is deeply unconcerned with the reader who was not there.

At the launch of Joe Felber’s exhibition at the Barr Smith library Douglas and Paquita Mawson’s great-granddaughter, Emma McEwin told us that she had written her book 'An Antarctic Affair' about her grandparents in order to keep them with her. This is a pretty good motivation for writing a book. Books are not going away in fact they are proliferating. Both books and catalogues do not reproduce exhibitions but are wonderful markers of them and of art, and pile up comfortably around the walls.

Stephanie Radok reviews eleven recent publications, Before Time Today: Reinventing Tradition in Aurukun Aboriginal Art

(Ed.) Sally Butler, 2010, UQP. RRP $44.

Once Upon a Time in Papunya

Vivien Johnson, 2010, University of NSW Press, RRP $34.95.

John Davis: Presence

David Hurlston with essays by Charles Green and Robert Lindsay, 2010, NGV, RRP $49.95.

Ingo Kleinert: Two Decades

Essays by Jenny McFarlane and Anne Virgo, 2010, SFA Press, RRP $25.

Joachim Froese: Photographs 1999-2008

Essays by Tim Morrell, Andrea Domesle and Ian Friend, 2010, QCP, RRP $55.

Renata Buziak: Afterimage

Essays by Victoria Garnous - Williams, 2010, QCP, RRP $35.

Substance of Shadows: Jutta Feddersen

2010, Murdoch Books, RRP $79.95.

Khai Liew

Peter Ward, 2010, Wakefield Press, RRP $45.

Rounds

(Ed.) Matthew Giles, PICA, RRP $45.

Barbara Hanrahan: A Biography

Annette Stewart, 2010, Wakefield Press, RRP $39.95.

Art Writing

Ken Bolton, 2009, CACSA, RRP $25.