In the 1920s and 30s Alfred Stieglitz (famous for photographing Georgia O'Keefe) took a series of photos of clouds which he titled Equivalents. The theory at the time emanating from Wassily Kandinsky was that abstract forms, lines, and colors could represent corresponding inner states, emotions and ideas. Margot Osborne is something of an evangelist for abstraction, beauty and nature and if she can bring the three together she is fulfilling her agenda. Like most freelance curators she has her obsessions and over the last three years, alongside other projects, she has brought 'Abstract Nature' to fruition, a project designed as stated by museum director Erica Green in the catalogue foreword to bring contemporary craft into the Samstag Museum Program but to do so imperceptibly so that the medium in which a work reaches resolution is no longer an issue.

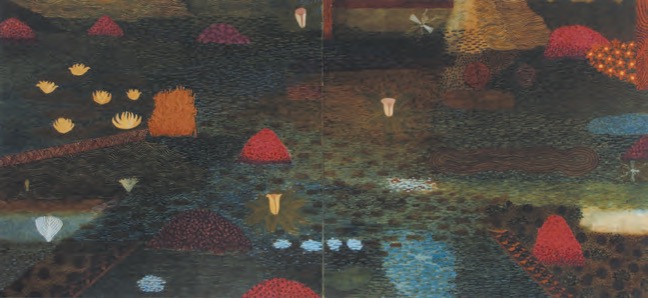

'Abstract Nature' brought together ceramics and painting, glass and photography, metalsmithing and works on paper, and many other less clear-cut media in a celebration of skill, beauty and response to patterns and designs found in nature. The works chosen by Osborne span Australia and it was a treat to see in Adelaide important works by painters like Robert Hunter, Tim Burns and Jenny Sages which are rarely seen here in the South of the South. In Burns’ large oil painting 'Like a long-legged fly upon the stream. His mind moves upon silence.' (a quote from a poem by W.B.Yeats) images of enlightenment from temple paintings mix with botanic forms and watery reflections in a meditative and enthralling way.

There are many reflections and correspondences in the exhibition, so much so that looking at it was like following a chain of thought or of perception. From the mica-filled chemical shapes made by Catherine Woo to the aerial patterns of Australian landforms recorded by Richard Woldendorp to the dotted glassworks of Giles Bettison and the striations of the paintings of Regina Wilson, the intensely detailed bark paintings of Djambawa Marawili and Wanyubi Marika, the soft glass landscape forms of Jessica Loughlin, the striped ceramics of Robin Best and Nyukana Baker and the scratched and inlaid ceramic forms of Pippin Drysdale, texture, shape and colour were thrown back and forth around the lower gallery.

Upstairs the work of three Adelaide jewellers Catherine Truman, Julie Blyfield and Leslie Matthews was arranged in cases. Truman was represented by an entire case of experiments and correspondences, both her work and odds and sods, which told a concentrated version of the story told in the entire exhibition, one of reflections and echoes. If Matthews and Blyfield had each been represented by just one delicate mysterious work it would have had a stronger impact than the series that were shown. Shona Wilson uses actual seeds, pods and other found materials to create enlarged diatoms, again just one work would have made it seem more precious. German photographer Karl Blossfeldt is famous for the great beauty of his black and white images of the structures and designs of plants that make them look like architecture or indeed metalwork. Like Wilson’s constructions of beetle wings and twigs the ceramic works of Angela Valamanesh draw on this close microscopic approach while Julie Ryder’s bright digitally printed silk is also based on microscopic forms though Ryder’s are invented rather than real and introduce a machine aesthetic that seems both inadequate and out of place. It lacks the irregularity and roughness of nature that Jenny Sages captures so well in her series 'Fragments remembered'. G.W.Bot has looked long and hard at the random markings on gumtrees. Her 'Tree of Life III' in which plants and birds seem to be about to emerge from bronze stumps is especially eloquent.