'Djalkiri' is about working together in a space that transcends difference and moves beyond time. In October 2009 during a ten day cross-cultural printmaking workshop at Blue Mud Bay in Arnhem Land, artists Djambawa Marawili, Fiona Hall, Liyawaday Wirrpanda, John Wolseley, Marrirra Marawili, Jörg Schmeisser, Marrnyula Mununggurr, Judy Watson and Mulkun Wirrpanda came together to begin their individual journeys towards this quietly groundbreaking exhibition of etchings and screen prints. After developing much of the groundwork for the plates directly on site, the works were ultimately resolved in collaboration with printmaker Basil Hall in Darwin, Brisbane and Canberra during several follow up sessions throughout the year.

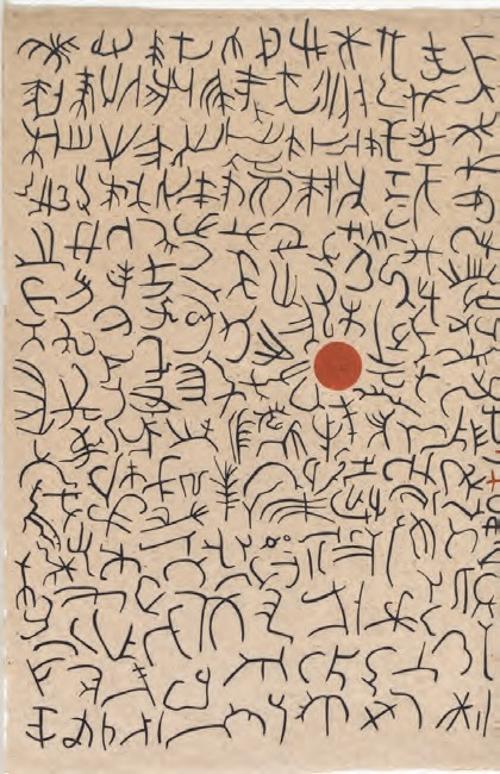

'Djalkiri' literally means footprint, however, in the context of Yolgnu law it speaks about the "spiritual foundation of the world". “We are standing on their names” is about walking together in the footsteps of the ancestors. Indeed, the artists and the works emanate from dimensions beyond the visible or tangible, as if drawing on a sense of the past manifesting in the present.

Whilst the binding threads reflect the experiences of the land and culture, the objective of the project was multifaceted. Together with Basil Hall, organiser Angus Cameron brought together artists, scientists and printmakers in a creative exchange with the aim of “juxtaposing Western scientific viewpoints and knowledge against the holistic perspective of Yolgnu people”. Essentially, however, this juxtaposition has slightly merged and fused through what Djambawa Marawili refers to as a “two way learning experience”: the “Balanda” (white people) way of doing art and Yolngu “way of making patterns, careful and tight”.

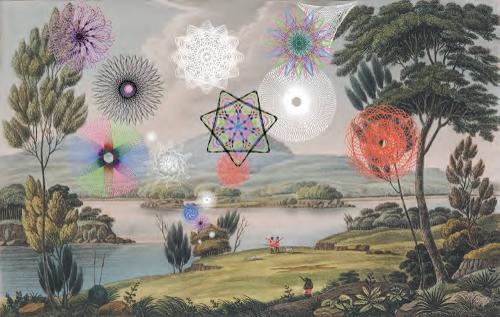

The catalogue accompanying the exhibition gives an excellent overview of the works, photographed by Peter Eve, with an informative essay on each artist, and further insights provided by Cameron, Howard Morphy, Will Stubbs and Glenn Wightman. Amongst such a rich offering of works and ideas, one thread in particular seemed to weave itself around the prints as I spoke to several of the artists, including Fiona Hall and John Wolseley. Interconnectivity. Concepts of interwoven space and myth are offset against detailed renderings of scientific observations. The recurring use of ochre hues and charcoal blacks creates a rhizomatic web. Refined etching and screenprinting methods become a technical 'lingua franca'.

Expertly reflecting the colours of the north, the artists have traversed and explored the spaces of Blue Mud Bay. Rather than contrasting knowledge systems, this project has, as Fiona Hall observes “transcended another realm”. Hall speaks of the way she feels “swept up by the way Indigenous artists organise the picture plane”. She reflects that “their idea of space must be vastly different to the way non-Indigenous artists see it”. Hall's sense of space is expressed “in a parallel way”, notably through her interest in botany, as seen in the 'Pandanus-Gungna' etching. This work, according to the artist, explores concepts of “bringing very little things into focus, where the minute and large might exist equally side by side”. It invites the viewer into a world beyond the threshold of visibility. Inside the involuting folds of the wilting dried leaves of the pandanus we experience a world of tiny insects and arachnids weaving their threads across the spiral layers. It is almost a microcosm of the rhizomatic interconnectivity between the artists themselves.

This interconnectivity is also evident in the work of John Wolseley who senses how events in deep time collapse and condense into myth. Through myth and symbolism, Wolseley observes “we find a way to learn the secret of the correspondence between all things; connections between something unspoken and the physical” like the spaces between mangrove roots; or even the creation of valleys by stingrays. 'Sea wrack: tide after tide - Baniyala' is a delicately layered ochre-tinted collection of fragments derived physically from the land and conceptually from fragments of stories relayed to Wolseley by the Yolgnu artists: the way in which a mangrove leaf bears a resemblance to a stingray and becomes part of the 'Baniyala' creation story.

With all these works, it seems we are viewing the prints through a microscopic eye. This eye allows us to enter an unknown world, a world in which the artist and the viewer are imbued with the magic of being able to see. And so it seems, like the inscriptions etched into each plate, and the enduring imagery of ancestral presence, this exhibition will itself make an indelible mark.