.jpg)

In 1999, the Californian artist Mungo Thomson quoted Bruce Nauman by having a number of holographic stickers made to read 'The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths' in the inimitable font of the purple ‘Magic Happens’ bumper sticker. The glib sense of humour underpinning Thomson’s sticker, coupled with an earnest faith in the social role of the artist, is emblematic of the world’s relationship to art and science after the recent global climate and financial crises — possibly more so than the mass recourse to mystic and alchemical modes of comprehension that the '2010 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art’s' curators, Charlotte Day and Sarah Tutton, envision.

Despite an eight artist overlap between 'Before and After Science' and Day’s 2008 'Lost & Found: An Archaeology of the Present' Tarrawarra Biennial, Day and Tutton’s curatorial hypothesis presented a reprieve from the torrent of biennial and triennial exhibitions that, for the last few decades, have almost unanimously touted an amorphous, fragmented and open-ended rhetoric of dialogical and ephemeral art to reflect the sense of uncertainty and mistrust pervading our planet.

Certainly many of the works in the exhibition were exemplary of a reaction to empiricism and an ensuing division between philosophical and spiritual enlightenment. The sculptures and paintings of Louise Weaver, Diena Georgetti and Mikala Dwyer formed the strongest argument for this separation, with Dwyer’s numerous consultations with a clairvoyant functioning as an integral part of her compositional process for 'The Additions and Subtractions' (2010). While Dwyer’s ring of sculptural objects evoked the magical presence of a stone circle, it also suggested the omnipresent eye of watchtowers: a feeling that became more ominous when traversing from the outer to the inner circle. But this interplay of earnestness and doubt — and of humour too — that underpinned Dwyer’s works was frequently left out of the curators’ continual emphasis on natural rather than rationalist philosophies. Thus at times their focus, as expressed in their catalogue essay, felt a little narrow because the very complexity of the artworks — and their combination of both faith and knowledge, belief and scepticism — was disregarded.

Justene Williams, Simon Yates and Stuart Ringholt were the key examples to suffer from this overly literal contextualisation. Williams’s work, a multi-channel video installation that documented her semi-shamanic attempt to channel the spirit of the Dadaist Sophie Täuber-Arp (Tauberguard Freak Mix 2008), for instance, drew upon the absurdist humour of early Dadaist performances.

Similarly, a trace of mockumentary comedy seeped into Stuart Ringholt’s AUM (2007): a video work based on the teachings of the Indian guru Osho. Drawing from the filmic languages of documentary and instructional self-help videos, and condensing the strict day-long meditation procedure into a half-hour DVD format, Ringholt intimated that spiritualism is automatically undermined when forced to adapt to the pace of Western living. While the curators posited that AUM is indicative of the artist’s belief that altered or heightened states of consciousness can be both artistically and socially useful, Ringholt’s work can also be understood through the binary paradigm of earnest belief coupled with self-reflexive (and comic) suspicion.

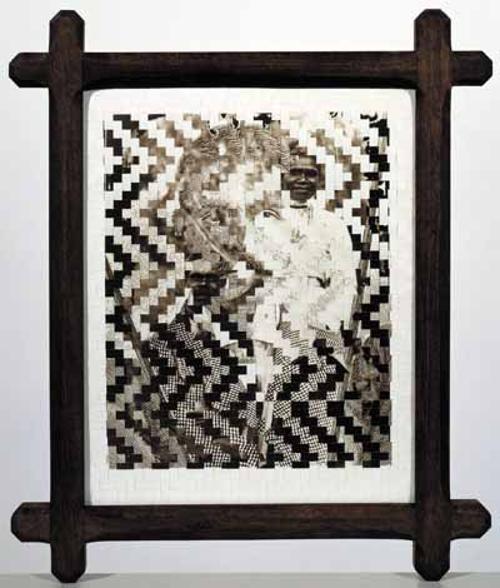

Not all the artwork in the exhibition made recourse to the buoyant virtues of humour, however. One emergent subtext that conceptually and poetically linked the works by Hany Armanious, Christian Thompson, Callum Morton and Nicholas Mangan was the commingling of death and ritual. Armanious’ sculptural installation 'Template' (2009), a scaled down version of an ancient Greek temple propped up on a ladder and accompanied by a pair of oversized sandal-clad feet, alluded to predetermined, ritualistic formulas for engaging with artworks in institutions. Thompson’s aural installation, 'Decent Extremist', 2009, similarly functioned as a tomb-like monument. His vestigial soundscape comprised multiple archival recordings of his father’s traditional language Bidjara. Wafting down from the entry stairwell into the lower sanctum of the gallery Thompson’s work served as an unearthly reminder of our endangered indigenous cultural heritage.

.jpg)

Callum Morton’s sombre 'Monument #26: Settlement' (2010), a hand-painted, fibreglass cast of a homeless person’s shelter, however, stood out as being particularly problematic. Again Morton infused architecture with biography — this time describing his dispossessed monument as a ‘tomb’ for himself. But sealed within the same museum-tomb that Armanious’ sculpture hinted at, isolated from the outside world which dispossessed people inhabit, and relying on a medium steeped in trickery, the work was rendered almost completely inaccessible to a wider audience. While aiming to address the displacement of individuals 'Monument #26' pivoted around a privileged discourse to which only the artist and contemporary art punters were privy. Even so many informed people actually failed to register it as an artwork.

An obvious point of comparison is the Spanish artist Santiago Sierra’s exhibition at the Kunst-Werke, Berlin in 2000. Here, Sierra presented gallery-goers with a series of real cardboard-box shelters, each of which housed an Chechnyan refugee seeking asylum in Germany. Sierra’s shelters did not inspire empathy from their audience, but rather pointed to the extreme economic and social divisions separating them from the art object/subjects — the collective tension that arose formed the artwork.

Mangan’s installation also engaged with the notion of a tomb monument, but his treatment of Nauru, the South Pacific island that endured heavy phosphate mining and, for the majority of this decade, was used by Australia as a place to detain and process refugees, also incorporated a number of regenerative qualities, hinting at the cyclical nature of economic trends in many post-colonial nation states. Borrowing alternately from the disciplines of art and documentary film-making, Mangan’s silent video automatically politicised its spectators by forcing them to improvise their own dialogue or voice over the smooth juxtaposition of images depicting Nauru’s ravaged coral limestone reefs and its tropical palm vistas.

The central driving force of the exhibition was, however, 'Ngayarta Kujarra' (2009), a spectacular 3 x 5 metre painting of Lake Dora by the Martumili artists group. The work defies a written account and, as such, pointed to the usefulness of Tutton and Day’s proposal to turn to the mysterious and unknowable in order to expand our properties of perception. But more than this, the painting (coupled with and reinforced by Day and Tutton’s thesis) presented an alternative method for re-envisaging Australian history.

Almost completely ineffable, but simultaneously more articulate than any restyled flag or history tome, Before and After Science’s greatest offering was this alternative approach to understanding Australian art. The myriad and inextricable intersections between reason and faith, science and intuition implicit in many of the artworks reinforced this significant curatorial gesture.