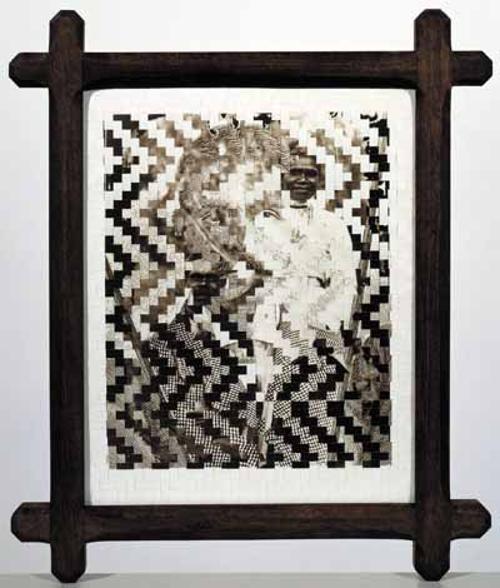

Ruth Waller's survey show at the Canberra Museum and Gallery is an exhibition of painterly intelligence at its best. This impressive selection of over one hundred works enables us to follow Waller’s restless energy from Sydney in the eighties to the issues engaging her today as Head of the Painting Workshop at the ANU School of Art. Many of us have followed Waller’s career as a series of highlights; this exhibition was an opportunity to see some of the connective paths over time.

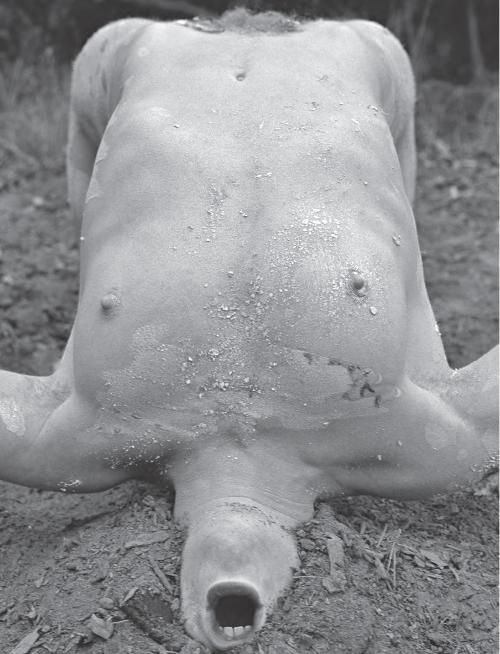

The 'Endangered Pawscapes' (1989) are still the raw and painful references to the politics of the environment that they were twenty years ago but they are also revealed here as part of a larger painterly exploration of representational strategies. Here Waller engages with depth and height, the imprint pressed into the soil and the bloody stumps rising out of it. Raw emotion and disciplined research into the practice of painting emerge as major themes throughout the exhibition. In her catalogue essay Deborah Clark writes that Waller is interested in '... the social, political and cultural context of art, and the ways in which painting, in particular, makes meaning out of the world’.

Waller’s Hospital Paintings were undertaken in response to the serious illness of a friend. This series of small works explore the reduced pictorial language and shallow pictorial space of the nursing ward. In this loaded space each element can be read unequivocally with varying degrees of relief and despair. The curtain conceals presence and reveals absence; visitations presage change and acquire portentous meaning. Perhaps there is no other space in the modern world which has so real a relationship with the deliberate confines of Flemish painting. Absence, presence, shallow space and the weight of each element are unpacked and explored in these small paintings.

.jpg)

'Dulle Griet' (2003) also explores the challenges of representing the three-dimensional. The starting point for this series was a cardboard maquette of the cautionary figure of Mad Meg (Dulle Griet) burdened with the meaningless detritus of life as she rushes through a Flemish painting. The maquette was then painted as a still-life, with particular attention to the inter-relationship of planes, lines and the compositional structure of the whole. 'Dulle Griet' pares back and teases out the internal logic of the practice of painting. Yet despite the most dramatic of abstractions, narrative persists and we follow the moebius-like strips of card as they twist in and out to describe form.

The tension between the process of abstraction and the persistence of narrative emerges as another insistent theme in Waller’s work. In 'Catalan song' (2002) her long term interest in pictorial space and illusionism is given expression as an apparently abstract canvas. 'Figure 10 (ice)' (2007) also reads as an abstraction although on closer inspection it reveals itself as the representation of a blank sheet of crumpled paper. Clark tells us that these works were made after the death of Waller’s father and the subsequent disposal of reams of unused paper. Here again a substrata of raw emotion infuses a work which appears to be a simple exploration of illusion in painting. As so often nothing in Waller’s work is simple.

In this survey exhibition we are invited to see familiar paintings carrying a larger conversation about the practice and history of painting. Discipline figures large as a concept, both in the sense of the repeated setting of pictorial challenges, and in the sense of the artist locating herself within the discipline of painting - exploring both its constructions and its unravelling, and the boundary between abstraction and representation. Curator Deborah Clark’s insightful essay is an added bonus. Waller’s larger practice is revealed as bold, raw, and above all the product of a disciplined mind.