.jpg)

'Cubism and Australian Art' is a meticulously researched and carefully assembled exhibition charting the influence of Cubism on Australian artists and the ways in which local artists imbibed, translated and disseminated its principles. It creates a trajectory from the 1920s through to 2009, tracing the legacy of the Cubist idiom on artists over each decade. Installed at Heide's central gallery in a loosely chronological fashion, the effect of the individual works is cumulative: each artist’s pictorial experimentation leads the viewer’s eye into the next, with a resulting amplifying of effect.

The curatorial agenda is expansive and contestatory. Firstly, the exhibition can be read as a riposte to Bernard Smith’s 1962 claim that Cubism had no influence on Australian art during the 1920s and 1930s. Paintings by Roy de Maistre, Roland Wakelin and Grace Crowley from this period indubitably demonstrate an engagement with the principles of Cubism. Secondly, the exhibition includes works by artists who would not necessarily claim the title of 'Cubist’ for their work, but whom the curators see as exemplifying an aspect of Cubism’s deconstructive thrust - undercutting the goal of verisimilitude to emphasise geometric plasticity of form. Finally, the curators mount an argument that the works of Australian artists were/are not mere derivations but re-workings and translations that serve to redefine Cubism itself.

This wonderfully anti-parochial approach valorises the works of artists like Anne Dangar and Dorrit Black, and elucidates their adaptations of Cubism as both assimilatory and experimental. In fact, the curators seem to be tacitly arguing, all the works in the exhibition can be seen through this prism – of both assimilation and transformation. 'Cubism and Australian Art' is driven precisely by the curators’ curiosity to identify the myriad ways, both subtle and overt, through which Australian artists have picked up and reworked the Cubist vernacular.

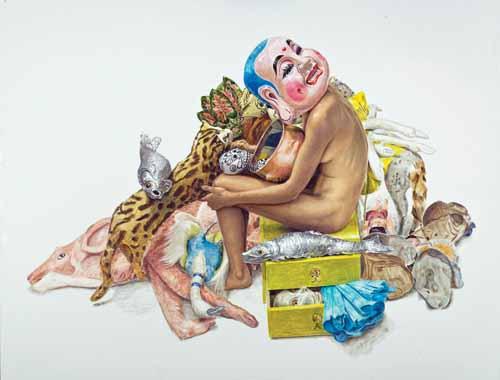

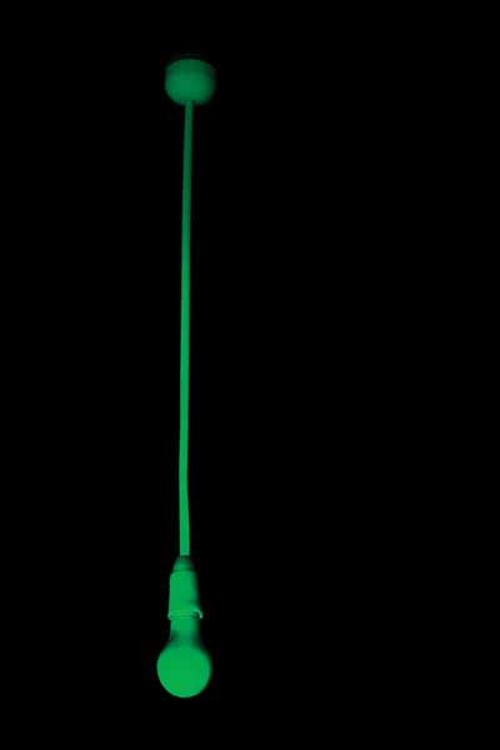

The adaptations are not singular but multiple – almost rhizomic – with Cubist principles appearing in works from one decade only to resurface in altered form in works by an artist from another generation. Like the multiple touchdowns of a stone skimming water, the effect is a ricocheting of influence. A centrepiece of the show, Daniel Crooks’ beguiling 'Static No. 9 (a small section of something larger)' (2005) slices video footage into horizontal bands and abstracts the original image of walking figures into twisting faceted ribbons, acknowledging a debt to Marcel Duchamp’s seminal 1912 Cubist work 'Nude Descending a Staircase'. Yet Crooks’ work also corresponds to the 1970s magazine collages of Carl Plate who sliced his images (vertically) stretching and imbuing them with a kind of corrugated movement – like views witnessed from the windows of simultaneously passing trains.

Justin Andrews’ geometric abstractions, produced and reproduced across media (collage, painting, animation) explode space into a vortex of splintered shards. While their 3-D, cinematic spatiality situates them in the present, the works visually pick up and extend the geometric explorations that George Johnson was formulating in his abstract paintings of the 1950s, as well as the intersecting planar compositions of Robert Klippel’s sculptures of the 1950s and 1960s.

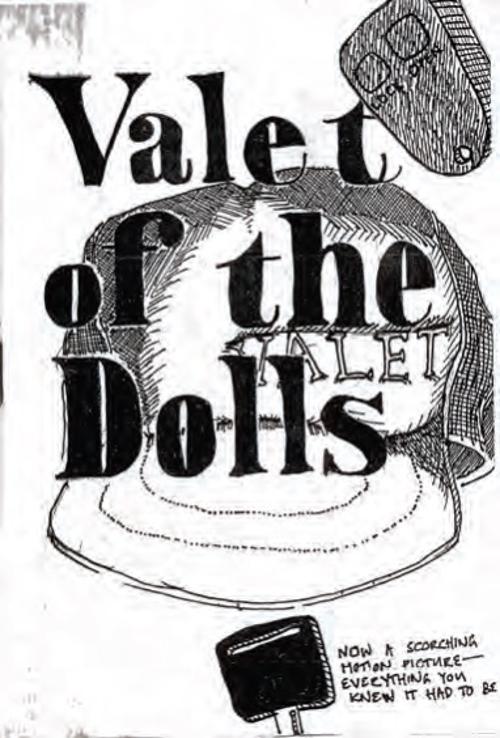

Some of the references to Cubist antecedents are knowing and wry, such as John Dunkley-Smith’s 'Pale Ale' which takes as its starting point Georges Braque’s identically titled etching from 1913. Re-enacting this iconic image in 1975 Dunkley-Smith photographed and transferred to film over 32 slides of a beer bottle, mug and napkin on an outdoor table, moving the objects between each shot. In 2009 the artist transferred the original slides to digital video to create a moving image work of subtle dissolves that wittily embody precisely the kind of fragmentary perception espoused by early Analytic Cubists.

Other references to Cubist ‘masterpieces’ are both tongue-in-cheek gestures and complex cultural statements on the entrenched binaries of original/facsimile and centre/periphery, such as Juan Davila’s 'Picasso Theft', a direct copy of Picasso’s 1937 'Weeping Woman' infamously stolen from the National Gallery of Victoria in 1986. Davila painted his replica two days after the theft and offered it as a substitute to the NGV which unmagnaminously declined his offer.

In many ways 'Cubism and Australian Art' serves to redress the longstanding bias against the geometric and non-objective in the historicising of 20th century Australian art. Instead of the well-worn trajectory of Antipodean figuration, the exhibition proposes convincing new narratives to contest this canonical terrain. Through curatorial acumen, the diverse works in the exhibition collectively argue for Cubism to be understood as a dialectical series of diffuse perceptual and pictorial strategies – with a very open-ended future.