Perhaps the common denominator of art and science is revelation, but I must ask myself what this exhibition would be like without the overindulgence in explanatory video, photography and text nudging it closer to the 'absolute'. Perhaps science is in the habit of explaining itself, but I would rather have my art come alone minus the briefcase and report. Exposé ensues during subsequent relations between you and the art; therein lies its beauty. If art was approached like a lateral thinking puzzle crossed with a 'Choose Your Own Adventure' book we would simply look forward to the quest.

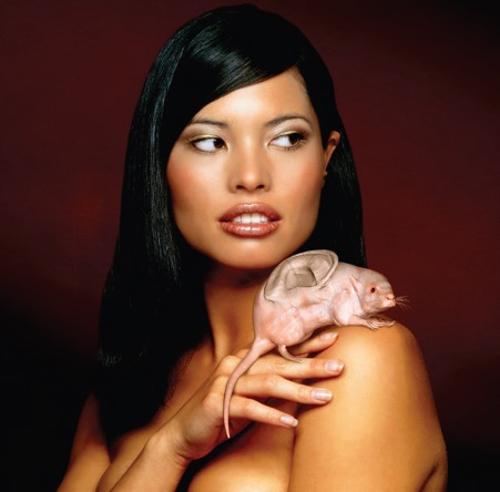

Janice Lally’s curatorial premise concerns the communication of ‘fresh insights’ into the understanding of the body and our relationship to it via the practices and interrelations of art and science. On first impression the show seemed slick and sterile; the edges trimmed meticulously with scalpel precision. Was perspex dished out at the door as some secret continuity weapon? Or did some of the artists bag a bargain at the latest plastics factory liquidation sale?

The first section depicts the language systems utilised by Catherine Truman, Ian Gibbons and Judy Morris to convey the body. The work includes photography, sculpture, installation, drawing, video and sound. I felt a little ‘lost in translation’ here, but perhaps these representations preserve the scientific end of the spectrum?

Noteworthy is 'Michael’s Cage: Series 1' by Truman - a three part paper and wood rendition of laboratory paraphernalia comprising a two dimensional dissection kit flayed open and layered in size graded repetition. Adjacent to this, the paper skins and nondescript wooden block inserts of pocket-sized parcels invite our eyes to fold along construction lines.

The night after the opening I dreamt of holding my breath underwater for four minutes – enough, Gabriella Bisetto articulates, to declare a human brain dead. If you have seen Luc Besson’s provocative film 'The Big Blue', then you will be familiar with the arts of freediving and static apnoea, with present day records pushing eleven minutes. Bisetto, like Besson brings an awareness to breath that is unique and haunting.

Bisetto’s series 'Measure of my Breath' consists of ten clear glass blown forms representing three minutes of breath, with the heftier twelve hours of breathing rendered in transparent plastic. The amorphous glass forms are quite literally solidified sighs, captured as if by some strange scientific contraption, imprisoned irrevocably. Dangling with beautiful delicacy, each breath casts its own shadow on the wall behind thus re-engaging tenuousness. Residual ‘mouth’ openings invoke ideas of the internal/external binary, the original fluidity and exchange of the artist’s air with atmospheric breath. This generates a gratifying cyclical thought pattern highly compatible with the artist’s original concepts.

Bisetto’s 'Twelve Hours of Breath' is immediately arresting due to its large proportions. While not pushing as far as Tehching Hsieh’s unfathomable time-based works, the initial awe of this work touches softly upon similar ideas of discipline. Weighing in at a hefty 4320 litres, this PVC contender is engorged with breath and the anticipatory sensations are palpable.

Rachel Burgess has sketched a dossier of dissection in Monstrance, alluding to the art of detachment. Yet on closer inspection I am quietly moved by the fact that her eye has caressed each fold, each filament. The drawing hand has guided each pencil line, smoothing and shaping with reverence and intimacy, rivalling any traditional artist/muse scenario. Burgess’ work is a balanced marriage of art and science; each lovingly executed drawing pinned between spherical borosilicate lens and the stainless steel table.

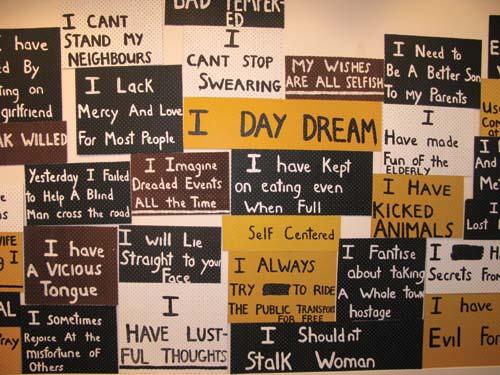

The response of Vicki Clifton to her partner’s post mortem report is truly touching. With the abundance of explication lining the gut of this exhibition I approached Clifton’s text work satiated. The opening lines reveal Clifton’s thoughts on ‘old injury’ present at the time of her partner’s suicide, describing the swimming pool hollow in his chest and the infancy of his broken heart. Each piece of ghostly text hovers, inscribed onto clear perspex, casting itself in darker reality on the wall behind. Clifton’s texts are juxtaposed with framed anatomical drawings by Burgess, denoting the discordance between the two.

In Lally’s favour, this exhibition did generate questions about the relationships we have with our bodies. These are not the usual suspects, but internal dialogues with interstitial stuffing. As Gibbons points out in his artist statement, there is no image depicting the ‘feeling’ of our internal structure. It is provocative to think that we are intimately acquainted with every mole, blemish and wrinkle on the surface of our personal lives, yet God help us if we had to identify our own innards in a line-up!