Since 2007, Brisbane-based artist-run initiative Boxcopy (founded by the fine art graduates Channon Goodwin, Tim Woodward, Joseph Breikers, Marianne Templeton, Anita Holtsclaw and Daniel McKewen) has exhibited some of the edgiest and most interesting explorations by emerging artists, with a stated mission to provide 'a contemporary art space dedicated to supporting artists in developing experimental and creative practices'. The group show 'A New Truth to Materials', curated by Raymonde Rajkowski, marked the end of the fruitful Metro Arts period for this ARI, which is due to reopen in August in a new location.

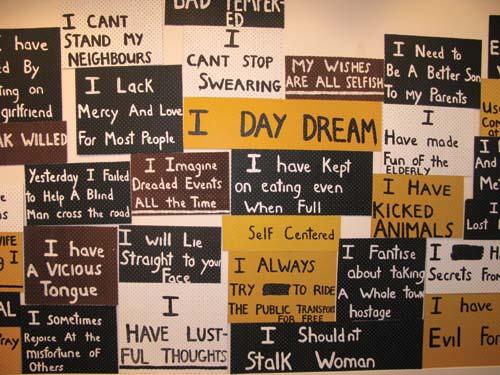

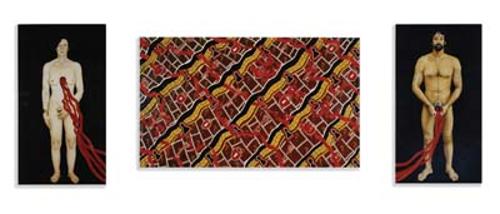

Taking inspiration from the historical attention to the nature of artistic materials by John Ruskin, initially associated with the handmade aesthetics of the Arts and Craft movement, and later, the ‘purity’ of Greenbergian modernism, the show mobilised the ongoing valency of ideas about materiality, authenticity and art discourse. Miles Hall’s reflexive examination of what it might mean to be a painter was articulated through raw combinations of basic materials and elaborate wall texts; namely, coats of paint applied to long pieces of medium gauge plywood in thick, single-colour ripples. Guarding the Level 3 foyer, these silent sentries were ‘art’ deconstructed to its most basic elements - didactic explanatory texts, basic board, and lots of paint.

Chris Handran’s installations evinced a similarly deconstructive, questioning approach to his chosen medium, photochemical photography. In one, the artist shone bright light through a glossy loop of suspended 35mm negative, creating surprisingly delicate coloured shadows. At once estranging this material from its normal context (i.e., to be printed into a positive photograph), Handran’s installation pointed the viewer’s attention to the nature and operations of analogue image technology. Handran’s other work consisted of numerous photographs the artist had taken, developed and then pasted together in mutant ‘brick’ sculptures. The blurred and abstracted content of the photographs was further rendered unseeable in their three-dimensional reimagining as art objects mounted on the wall and on a plinth. While this work also generates subtle questions about readability, photography and power, Handran, like Hall, is asking questions about his medium by pulling apart and reassembling its material in new and unexpected ways.

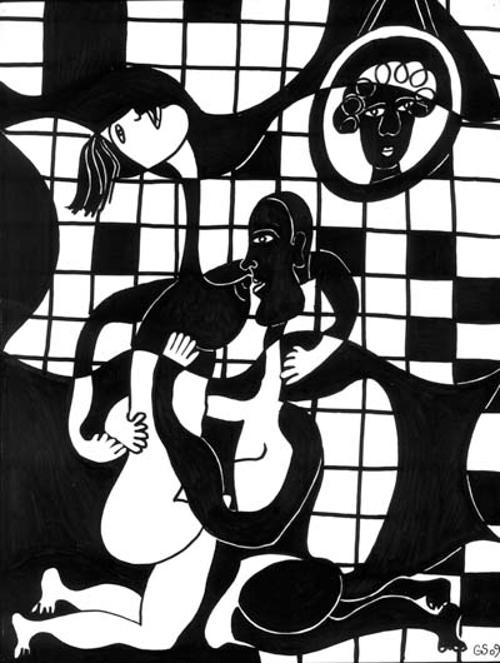

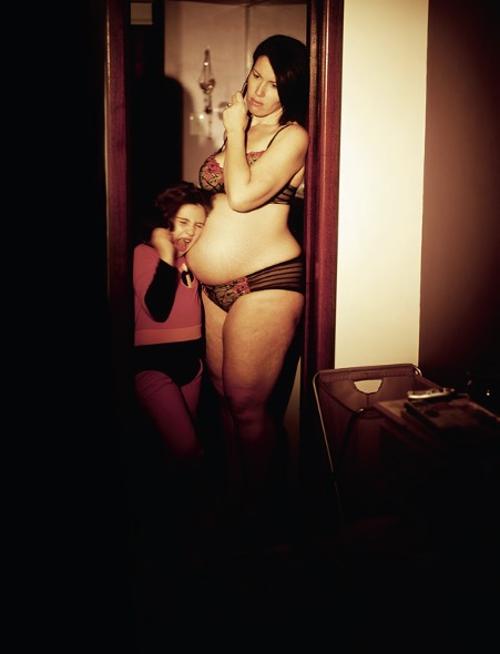

Questions around photographicity (the belief that the art of photography resides in its self-referentiality, its revelation of the formal properties intrinsic to the medium, its history and tradition) and documentary truth were raised by Chloe Cogle’s new Dutton Park cemetery work. Since 2007, Cogle’s multimedia performances have critically combined the projection of 35mm slides with an authoritative spoken-word performance that purportedly ‘explains’ the content of the images to the audience. Taking the classical art-historical lecture model, illustrated by ‘exemplary’ slides, as her point of departure, Cogle’s deadpan speeches generally begin with factual, plausible statements that gradually incorporate half-truths, exaggerations and outright fabrications. The instability of the ‘visible evidence’ suits both the found, gifted and family slides Cogle has used previously, as well as the new images purpose-photographed for this work. Inspired by accounts of Brisbane’s cataclysmic 1974 floods dislodging gravestones, the performance involved the projection of long-exposure black and white slide photographs of the artist in the cemetery; collaborator Luke Walsh’s resonant, textured soundscape incorporating processed sounds of water, voices and feedback distortion; and Cogle’s characteristic imperious monotonal delivery. Proving that fact can be stranger than fiction, Cogle narrated the (true) tale of how the headstones, gathered up in the relentless force of the floodwaters, were presumed lost, until they were excavated some years later and then, as the tabloid 'Courier-Mail' put it, ‘secretly used as landfill by the council’ in its development of controversial new transport initiatives.

Ross Manning developed his work with used, abused and ‘cracked’ electronics to produce an installation and performance revolving around a deconstructed consumer data projector. The ‘accidentally’ generated projections, brilliant shafts of pure digital colour, from Manning’s customised components assemblage, flitting nervously around the very dark space served as the perfect foil for the artist’s typically dynamic and slightly demented improvised electronic music performance, and a fitting conclusion to an impressive endeavour. In different ways, the interrogative approach taken by the artists to their materials revealed not just truths, but a whole range of promising creative and critical possibilities.