As its colonial history is so apparent in its buildings and the general John Gloveresqueness of its landscape, visiting Tasmania necessarily involves a heightened sensation of an encounter with the past. One of the other histories of Tasmania, that of ecological awareness and activism, is also ever-present in the identification of Tasmania as literally being its wilderness, primeval and beautiful.

Tasmania is an edge of civilisation facing the Antarctic, half wilderness, an island, and a committed outpost of contemporary art. The relevance of contemporary art to Tasmanians and their history was convincingly embodied in the visual arts program of 'Ten Days on the Island' especially in its major exhibition 'Trust' curated by Tasmanian School of Art head Noel Frankham. 'Trust' involved commissioned work by eight leading Tasmanian artists embedded in and responding to five National Trust buildings across the island. This located series of exhibitions made the contemporary art pilgrim take journeys into places redolent of the upper class history of Tasmania as well as throwing conventional National Trust audiences into an encounter with the sometimes oblique commentaries of contemporary art.

Some of the larger National Trust buildings are used for functions and a wedding taking place at Runnymede when I was there was flanked by some of Pat Brassington's haunting and haunted images about feminine fates, a somewhat braver backdrop than the flowers and usual wedding paraphenalia.

The 'Trust' pieces that worked best and gave a sense of delight as well as thoughtful prodding to the exercise were those that were integrated into their sites like John Vella’s free-standing column at Clarendon which was almost invisible. I saw the sign and looked around for the work; it was right next to me yet could have been there always, joining the other columns in the house’s neo-classical façade except that Vella’s column was located right in front of the heavy front door. His research showed that when evacuating a building, a column in front of an exit makes for a more orderly and effective escape.

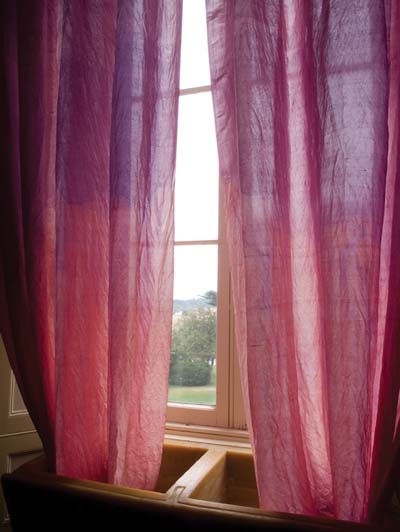

Also at Clarendon Lucy Bleach’s sensitive work of two long silk curtains, dyed purple with lichen, that hung down a long window and into a trough cast in yellow beeswax was also incorporated into the house though at the same time odd and fey. Lichen dies out early in an over-toxic environment as well as being the first organism to introduce life back into denuded landscapes. Michael McWilliam’s carefully painted table and other works also referred to the environment, a fox on a sofa in 'Settling In' looked unblinkingly at viewers while Julie Gough’s three hour video listing land grants of the region against a journey on the road was situated in the very cold basement not far from a hat-stand made of deer antlers.

Mary Scott’s work at Home Hill, once the home of Enid and Joe Lyons, Prime Minister of Australia 1932-39, engaged with local embroiderers, utilised the domestic metaphors favoured by Enid (the first woman to be elected to the Federal House of Representatives 1943-51) in her speeches in Parliament and induced wonder about the twelve children who have left so little trace in the house and for whom there scarcely seems room. At Oak Lodge the photographs of Ruth Frost caught the light in empty rooms, evocatively suggesting presence and deepening absence. In Penghana, the one time mine manager’s house at Queenstown, a geographic video drawing by Martin Walch took you into the attic where you could peer out of the windows from which the mine manager used to spy on the town. Walch’s work was also meant to be but was not on in the amazing recently restored leopard-patterned Paragon Theatre with its mini-sign of coloured stones spelling out Queenstown Rocks. Queenstown is a place of depth and mystery, savage printed T-shirts, Amanita muscaria and LARQ (Land Art Research Queenstown), the studio, gallery and environmental art residency run by artist Raymond Arnold who spoke of manmade landscapes that are now seen as important heritage sites just like wilderness sites and of the potential declaration of a UNESCO Geopark in the region.

Contemporary art in Tasmania will soon be even more enveloping when the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) opens at Moorilla. It will be the biggest private museum in Australia with permanent and temporary galleries of artworks from all over the world from Ancient Egypt to Chris Ofili and the Chapman Brothers. Like the Getty or a Guggenheim Museum it will be a destination as well as a temple to art. Its patron David Walsh seeks new ways to show and interpret art and has fabulous plans for future shows including collaborating with French curator Jean-Hubert Martin, most famous for curating 'Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the Earth)' at the Pompidou in 1989.

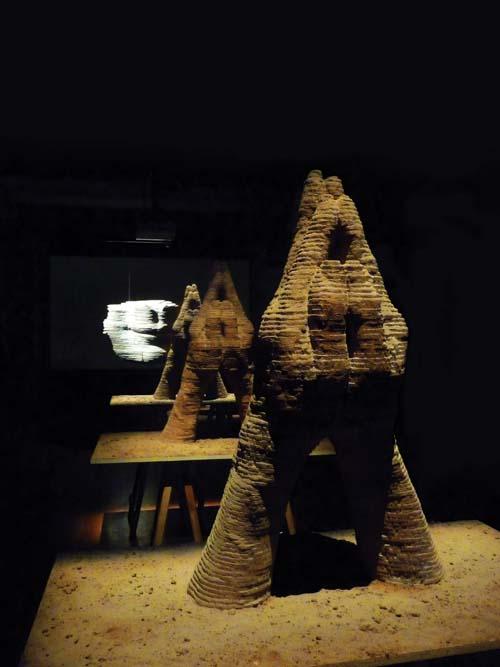

New Zealanders Brett Graham and Lisa Reihana showed 'Aniwaniwa' at Rosny Farm. On arriving singing and music from the barn could be heard and inside rows of beds on the floor covered in black sheets and pillowcases were placed for viewers to lie upon and look up at the large circular eyes like huge black tyres carved by Graham within which Reihana’s narrative about Maori people filmed underwater was shown. It told the story of Horahora a hydroelectric dam and village in New Zealand which was flooded in 1947 - especially appropriate to be shown in Tasmania where the flooding of Lake Pedder led to the formation of the world’s first Green political party in 1972.

In 'Evolution', curated by Juliana Engberg, Patricia Piccinini’s work took over TMAG (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery) like something from another planet or a cutting edge display from the Smithsonian on hybridity and futurology. The works were deployed around the museum alone as well as within established Museum displays. It was even possible to handle one as gallery guides handed around 'The Offering', several small but surprisingly heavy lightly haired sleeping baby creatures that you could touch. Their ears and skin are soft. Piccinini has a thing about skin and her creatures rarely have much fur – one of the strongest distinguishing features of an animal as compared to a human is fur – rather they have sparse hair and this is what makes them seem more human than animal though clearly they represent an as yet unknown future borderline where the body has mutated or evolved to take on new roles.

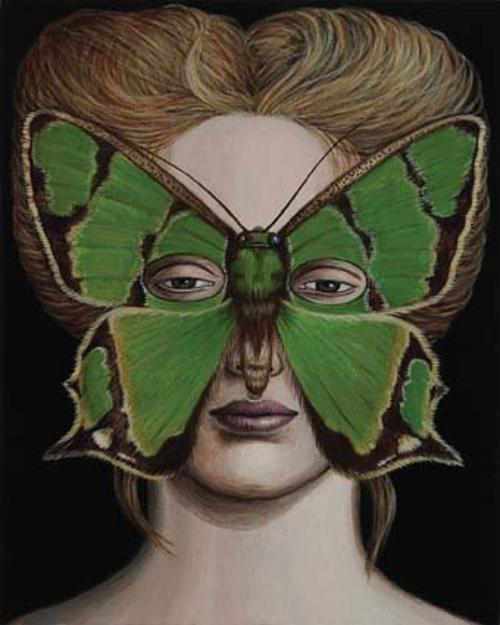

Their skin is often folded in strange ways, or has taken on the function of cocooning another animal and generally shows great age, spottiness and wear. Though the creatures are new they are also old and weary and there is generally a nightmarish post-apocalyptic quality to their existences though children love them. Perhaps because in some way they are like animations made flesh. In the colonial gallery 'Progenitor' a winged froggy creature leaps from its zippered cocoon on the wall to stick onto the face of a model of Piccinini. In another gallery the mutant 'Bottom Feeder' stands/gropes within a pre-existing diorama of common wildlife in the Tasmanian countryside which has been despoiled with rubbish for the exhibition. The 'Bottom Feeder', who looks like something from a Hieronymous Bosch painting is there to eat the rubbish with its shark-like mouth.

There are also works that involve scooters morphing into animated beings. In 'The Stags' two males fight it out with multiple rear vision mirrors. Every time I see a scooter now it seems to be about to twist around like a snail. Clearly the TMAG with its historical and now rare conflation of art gallery and museum and its also rare film footage of the Tasmanian tiger and its stripey back, stiff front legs and kangaroo-like tail seems just the right place for Piccinini’s strange and mournful hybrid creatures that seem to look into an uncontrollable future where evolution has lost touch with practicality in response to new unnamable conditions.

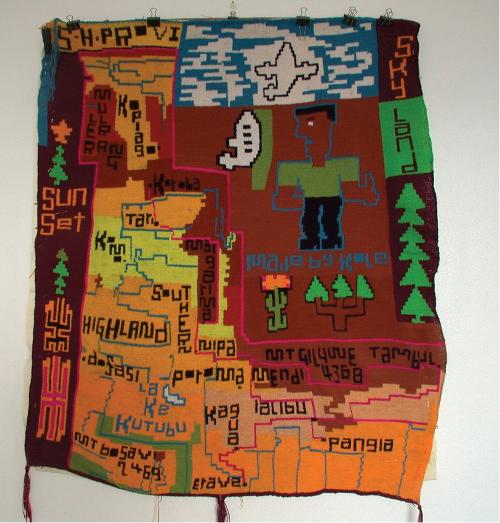

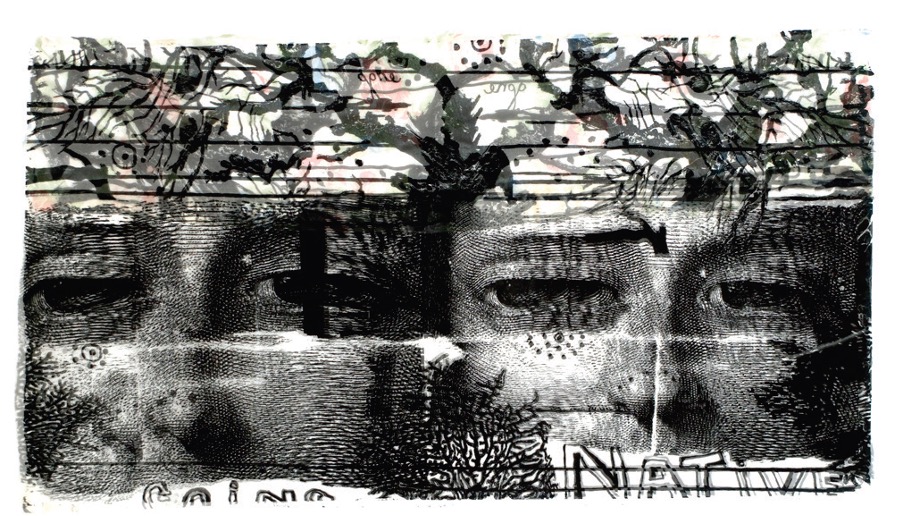

At Cradle Mountain Chateau’s Wilderness Gallery, a substantial exhibition called 'Strata' curated by Tracy Thomas put papermakers, photographers and printers together to make collaborative works that on the whole suggested earlier times. Most successful were the three photos by Darren Jew taken in PNG harbours which were printed on tapa made by Melene and Paulene Tonga. The scale and texture of the tapa made it seem as if the photos were taken by Captain Cook. In the Burnie Print Prize at Burnie Art Gallery the linocut print called Going Native by Heather Shimmen also evoked the Captain Cook era and was cleverly printed onto organza as well as paper so that it possessed the sensation of a doubletake. The Print Prize was a voluminous and fascinating survey of printmaking across the country. Also working well in Burnie at the Council Chambers atrium was 'Switch' by Tracy Luff, great chains of corrugated cardboard growing in the corners of the space and hanging down in long chains that moved when you walked.

In Hobart’s Plimsoll Gallery 'You are Home' from Taiwan curated by Megan Keating presented many facets of the unique and strange city life of Taiwan. In particular 'Disappearing Landscape – Passing' by Yuan Goang-Ming had a strong kinaesthetic effect that gave you the sensation of flying swiftly into and through buildings. The repetition of this video sequence, in a house which went from ruin to immaculate in seconds, was hypnotically dreamlike. In 'Chance Encounters' curated by Mary Knights and Maria Kunda at the Long Gallery a further dreamlike state was encouraged with a collection of quirky artworks ranging from haiku found in the daily paper by Barbara Campbell to the video of the first woman on the moon by Aleksandra Mir.

Driving out of Hobart I thought a lot of wood was floating in the inlet but it was all black swans, practically each one with its head looped down under the water, fishing I suppose. The 'Icelandic Love Corporation' who showed at CAST Gallery have been making work on bird and animal behaviour for some time and in Tasmania were able to encounter real black swans while thinking about Black Swan Theory though they were not introduced to Ern Malley.

At Devonport I took time out from the cutting edge to see 'The Spirit of the Sea', a 'lifesize’ statue of what could be Neptune or Poseidon, placed at the entry to the Mersey River where the Spirit of Tasmania ferries cars and passengers over from the mainland. The figure is dwarfed by the sea and you can’t help but think that a very very large foot or even simply an enormous toe, with a nod to George Bataille, would call more strongly on the imagination of the viewer. The converted church of the Devonport Gallery, which holds a Philip Wolfhagen mural in a dome like a prayer to local landscape, also contained the exhibition called 're-earthing', curated by Vicki West, of work by three Tasmanian Aboriginal artists Lola Greeno, Lorna Riley and Denise Ava Robinson. Robinson’s work was the most innovative involving the bleeding of red ochre through a wall made of white cement blocks.

'Siren' by British artist Ray Lee at Inveresk in Launceston was a sound and light work that viewers were encouraged to walk around as about fifty sirens were turned on and spun on tripods first slowly then more rapidly, finally in the dark with lights, and then unwound again. The work was one of endurance and curiosity though lacked a climax. The best part of it for me was near the end when having stopped walking around as instructed I sat down against a wall and found that as I looked at the entire work from side to side the red lights on top of the sirens moved with my eyes and seemed to be drawing in the dark.