In 'The enchanted forest: new gothic storytellers' curator and artist Jazmina Cininas presents her own linocuts alongside the work of five other contemporary artists who re-interpret flora and fauna through the lens of gothic storytelling. A range of mediums are present, Milan Milojevic and Cininas are printmakers, while Deborah Klein and James Morrison exhibit paintings, and Louise Weaver and Louiseann Zahra-King show installation works. Drawing on the traditions of fables and folklore, each artist has built over their careers a delicate natural world and an intricate visual language to depict it. As these realities interface in the gallery space, the viewer wanders between wolves with women's eyes, beautiful moth-masked girls, fallen giants, and frozen birds under glass bell jars.

Whilst such a premise may seem escapist, a fantasy in stark contrast to recent exhibitions treating environmental concerns such as RMIT’s 'Heat: Art and Climate Change', the works presented in 'The enchanted forest' do seem informed by a desire to reconcile the conflict between contemporary society and the natural environment. By turning back to the precedent set by the 'gothic’, the artists have found an approach to visualizing dense forests and the creatures that inhabit them. For a contemporary gothic storyteller, the stories of the mythical and dangerous creatures hidden in the foliage are peppered with references to contemporary concerns, such as sexual politics, colonisation, and the degradation of the natural environment.

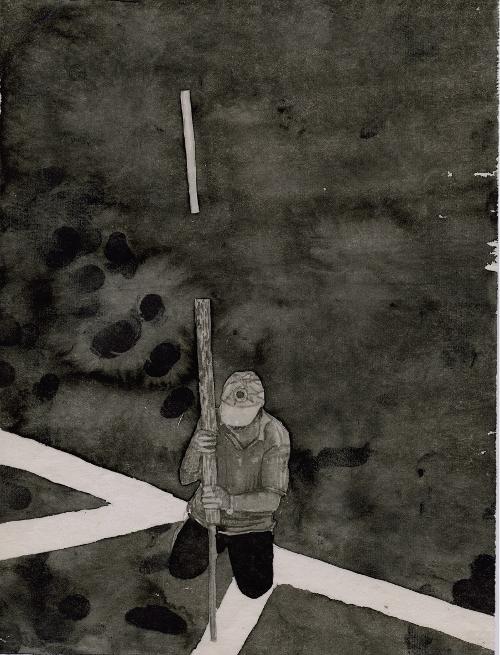

James Morrison’s five-paneled panoramic oil painting, 'Freeman Dyson', depicts an apocalyptic Australian bush landscape littered with skeletons and a burning sunset in the background. Outsized magpies picking at the remains draw the eye across the scene to a collapsed man whose torso spills into view from outside the frame. This man is an explorer, most likely from another planet given his astronaut’s helmet and futuristic clothing. The title refers to American theoretic physician and mathematician Freeman Dyson, known for his theories on futurism, space colonies, and the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence. Creating the panorama specifically for 'The enchanted forest', Morrison intended to show a world where time had ‘either slowed down, or stopped’ - a ‘backwater in time’ – suggesting an approach to storytelling enriched by science fiction and ‘traveller’s tales’ such as Jonathan Swift’s 'Gulliver’s Travels'. The moment captured is one of colonisation: the explorer, strange and foreign, has landed on what appears to be terra nullius.

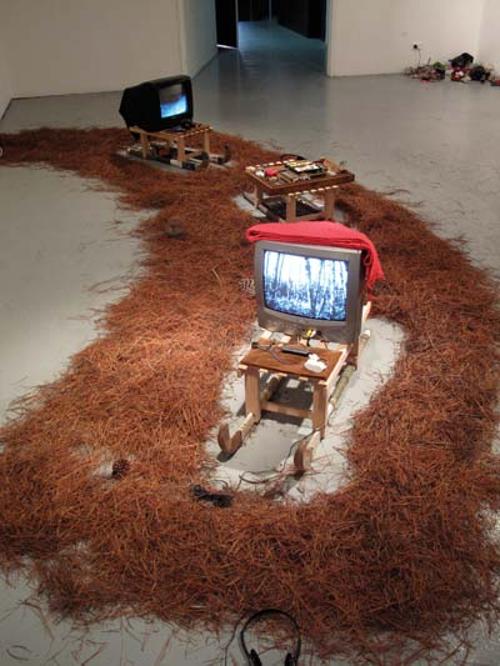

Louise Weaver’s installation of colorfully dressed wild animals 'Moonlight becomes you' presses pause on a moment in another liminal space, the forest in a moonlit clearing. Weaver’s hybrid creatures have developed new skins, like bower birds collecting designer threads and crocheted lambswool to disguise themselves at the masked midnight ball for otters, squirrels and possums. Reminiscent of the theatrical, crackling mood in Shakespeare’s 'A Midsummer Night’s Dream', 'Moonlight becomes you' creates a playful sense of possibility – that anything can happen in the forest, and nothing will be remembered the next morning.

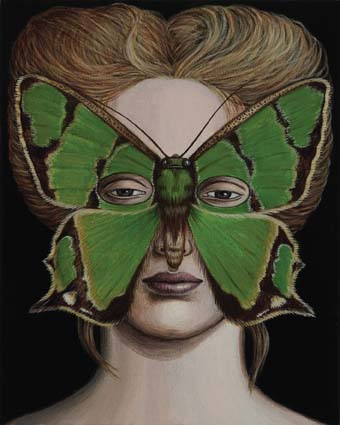

But it is not all anonymous nighttime revelry. As in the storybooks, 'The enchanted forest' is filled with glowing eyes that seem to be trained on you from all perspectives. Sometimes these eyes are human, such as Cininas’ female-eyed dingo in 'Rima knows the curse of being born on Christmas Eve', who looks out from the winter landscape as if to size up the viewer. Other eyes are passive, like those in Deborah Klein’s 'Chelepteryx collesi', 2007, from the series 'Moth masks' wherein women are morphed with open-winged moths, both creatures pinned still by the artists’ gaze. Such constant surveillance hints at the other essential ingredient of any gothic fable – an element of real danger. If there’s anything critical to be said of 'The enchanted forest', it would have to be that the creatures seem toothless – the nastiest ones have been censored out like the whitewashing of the original Brothers Grimm’s fairytales. This, however, may be an attitude change symptomatic of current environmental fears – these beasties in the forest no longer deserve our fear, but need our protection.