This is uncharted territory.

In December 2007, Australia signed onto the Kyoto Protocol. In doing so, it emerged from the shadows of the Anglosphere to claim an independent role as a 'middle power'. Australia has now boldly assumed the position of broker between the established powers of the North and the emerging interests of the South. Are we up to the challenge?

In Bali, the world stood to applaud Australia’s conversion. Global consensus is critical to the success of the Kyoto Protocol. In the period leading up to Bali, the USA had refused to ratify the protocol because it exempted China from shared targets. But here was its loyal ally, Australia, finally agreeing to the process. Would the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases be next?

By the end of the meeting, the USA hadn’t budged. It was left to the two most North-centric countries of the South, Australia and Argentina, to extend the meeting an extra day and thus enable the USA to come on board. The USA hasn’t ratified yet, but it is still in the conversation.

The Kyoto Protocol continues to operate as a key platform for bringing together the two halves of the world - the 90% in poor countries who produce most of the world’s goods and the 10% in rich countries who consume them. The momentum in this conversation now continues into the domain of finance with the expanded G20.

The Kyoto Protocol involves more than just haggling over carbon targets. It represents a fresh conversation about where the world is heading. What seems new is the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’. Those two simple words, ‘common’ and ‘differentiated’, contain a world of meaning.

To begin with ‘differentiated’, the first principle of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is that ‘The largest share of historical and current global emissions of greenhouse gases has originated in developed countries’. The argument goes that it is the West’s rampant consumerism combined with slash and burn globalisation which has clogged the atmosphere with carbon.

If we had only this proposition, we would be in a familiar situation. The global North needs to acknowledge its sins and undo the damage its greed has wreaked on the environment. So what’s new?

The other element – ‘common’ – twists our focus in a new direction. The future is not determined only by the North’s actions. A large measure of future economic activity will come from emerging nations such as India and China. Here is the second proposition: the future is a global responsibility. There can be no agreement without consensus from all, rich and poor alike.

The Kyoto Protocol is a process of building this precarious consensus. The voice of the South has been particularly strong so far. Representatives from Brazil, India and China argue that they should not be deprivedof the fruits of economic growth, simply because the North used up the resources first. The South should have lower targets for carbon emissions so it can catch up with the North.

So the tale continues. It is as though a ship was adrift, lost at sea. The officers, accustomed to double rations, are demanding that everyone reduce their intake. But the crew are already on subsistence rations. They revolt: why should they suffer when it was the greed of the officers which so depleted the food stocks? The officers respond that without their knowledge of navigation, the ship has little chance of finding land. And on it goes.

On the world stage, Australia has been granted the role of interlocutor. At the G8 summer in Toyako, last July, the Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda gave his Australian counterpart six minutes in which to bridge the gap between USA and China. Kevin Rudd chose this moment to say that Australia wanted to see a ‘grand bargain’ – a ‘new grand consensus between developed and developing countries so that we can act together to bring down greenhouse gas emissions in order to save the planet’. The language is a little on the Homeric side, typical of ‘this’ Kevin Rudd, but the intentions are noble.

So, that’s the talk among the suits. How does this ‘grand bargain’ filter down to life on the street? While there is no doubt that emissions targets will eventually affect how we use power in our everyday lives, there’s also the potential that the new global dialogue will change how we see ourselves in the world.

In many ways we are still fixed within the old world, following the first proposition of ‘differentiation’. Campaigns like Make Poverty History reinforce the missionary relationship in which an active North solves the problems of a passive South.

Celebrities tell us ‘We have to help the starving children in Africa.’ We certainly do, but there’s a negative undertow. Does focusing on the plight of children mean that we are less likely to take seriously the adult intellectual challenges emerging from countries like Africa? The charity icon of the wide-eyed innocent child casts its shadow in the stereotype of the sweaty corrupt official.

Missionaries are not all bad. Many of them, like Heidenreich in Hermannsburg, attempted to save first peoples from the evils of Western civilisation. But no matter how noble the missionary, most of us acknowledge that the relationship of dependence set up between the white minister and his black congregation is itself a form of oppression.

So here we have our current predicament. The West is no longer the only agent of change. How do we maintain dialogue between cultures without re-inventing the missionary yet again? But how can we think differently? Doesn’t the alternative path involve a callous indifference to the suffering of others? How can rich and poor countries become partners?

Existing models are not up to this challenge. There are signs that the post-colonial paradigm is losing its relevance. Post-colonialism has played a critical role in highlighting the impact of British colonialism on native populations. But writers in countries of the global South like India are beginning to claim that there is more to their culture than its reaction to Western imperial interests. How do we engage with the growing independence of the global South, mutually supported by increasing South-South links?

We are in need of alternative models for global dialogue. We move now from suits to t-shirts. Generally, it is artists who give themselves license to stray from the well-trodden path. Until now, the dominant model for cultural exchange across the great divide has been missionary practice. According to this model, an artist from the North goes South in solidarity with victims of oppression. The artist ventures forth to save fragile communities from the ravages of colonialism and political violence, as the church once went into remote indigenous communities to protect them from settlers. Consider Anthony Gormley’s global project with Chinese peasants in the Asian Field. Like religion, art can become an evangelical project to save the marginalised from Western materialism.

Missionaries go forth with great dedication to justice and universal upliftment, but unwittingly they can also reinforce dependence on white power. Over time, many artists can be seen as scouts for tourist operators, shopping mall developers, and generic cultural commodification. Visit Tahiti and buy your Gauguin t-shirts.

The contributors to this issue describe modes of engagement that seek alternative paths.

While the burgeoning Asian art market promises to invigorate the Western scene, it brings with it the hazard of commodification where images are constructed for the global gaze. Haema Sivanesan considers the way three artists – Ruark Lewis, Sharmila Samant, Khadim Ali and Jayce Salloum – seek to maintain a critical space for art. Zoe Butt locates this challenge within China as the Long March Project develops its latest project in Vietnam. A Western interest in Asia can overlook its own internal dialogues.

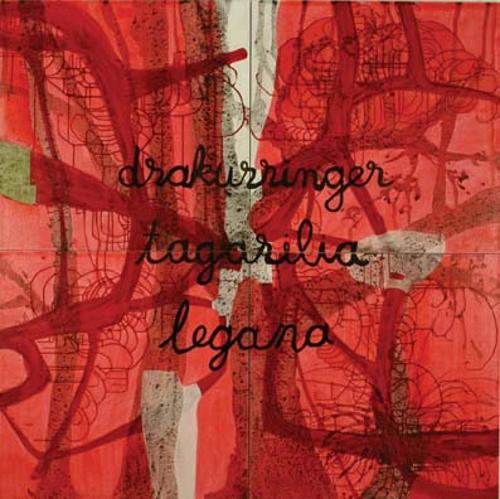

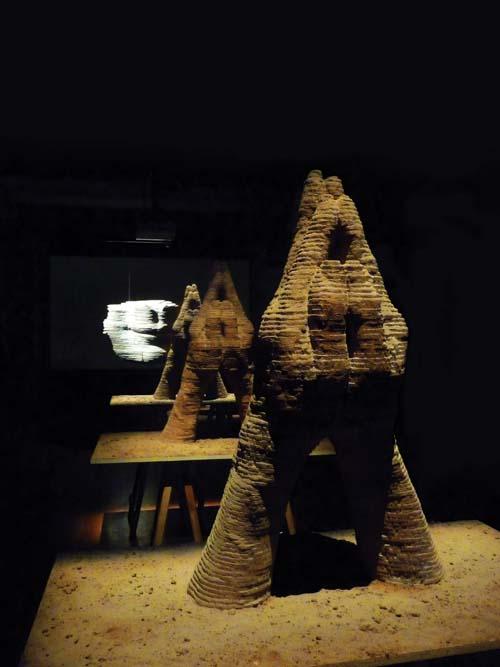

Janet de Boos speaks from firsthand experience in making work for the Chinese ceramics market, and cautions against the sense of superiority which is quickly unmasked by Chinese willing to do business. The practice of visual artists working with local artisans has generated much critical art, particularly from the Philippines. Neil Fettling describes how the artist David Griggs negotiated the involvement of billboard painter Rene P. Oserin. Greg Pryor describes his own business with Taiwanese artists and their shared amazement at the re-discovery of fibre mysteries. Closer to home, Ruth Hadlow reflects back on life in Australia from the seeming chaos of West Timor.

In taking a new look at Paul Carter’s Nearamnew, Emily Potter questions the denial of history that is implied by our understanding of climate change. Veronica Tello considers three artists – Lyndal Jones, Santiago Sierra and Armin Linke – who have looked to North Korea as a limit to cultural understanding.

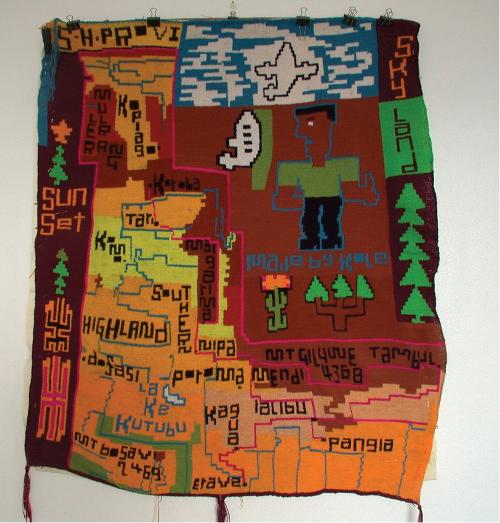

After controversy over the theatrical design in Musée du quai Branly, Jacqui Durrant takes the bold step of asking Cook Islanders themselves how they would like their art displayed. Susan Cochrane accounts for recent experimentation with the bilum form in Papua New Guinea. Further down south, Helen Vivian describes the collaboration between poet Jim Everett and artist Jonathan Kimberley as an ideal form of dialogue. Finally, Kylie Waters reflects on her own missionary background and how her art attempts to tread a path between paternalism and an understanding of Indigenous rights.

Interspersed between these contributions are scenarios which invite you to consider how the relationship between artists in rich and poor countries might be transacted these days. You can be the judge of that.

The artists featured in this issue point to promising paths ahead. They suggest a step forward for relational aesthetics, beyond the festive gatherings at biennales to more strategic engagements across cultural divides. They promise an art whose creative value rests in the way it invents terms of engagement for the various interests at play. They open the possibility that artists from rich and poor countries might come together in some middle ground, speaking a common language of materials. The acknowledgment of non-indigenous identity might lead to more reciprocal forms of reconciliation. There might be a fair trade between the design resources of the North and the South’s capacity to realise it.

We may well start this dialogue with the face painted by Australian-Indonesian artist Dadang Christanto. (See cover.) Set against a bronze background, the shimmering face evokes the classical impenetrableness of the oriental other – eyes without seeing and mouth without voice. Framing this portrait are ghostly forms that seem to be tied to a third eye. This mystery of difference is accompanied by an aesthetic possibility of free play. The emergence of creativity from incommensurability reflects well many of the paths followed by contributors in this issue.

The purpose of this issue is not to present a final solution, it is instead to consider how contemporary artists are exploring the various cracks, nooks and underbellies of the global highways linking North and South. As a reader, you are invited to share these journeys. It is unlikely that any of them will represent ultimate destinations. But their experience may help us find our own way. As they say in Mexico, walking we ask questions.

Note

The use of the terms North and South are used here as shorthand ways of talking about the relation between the 10% rich and 90% poor nations. The directional metaphor provides a less hierarchical framework than that suggested by alternative terms such as ‘first’ and ‘third’ world, or ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ nations. Previously hegemonic interests are also referred to as ‘the West’ when referring to a specific set of cultural values. For ongoing discussion on this usage, see www.southernperspectives.net. For further information about new dialogues, see www.craftunbound.net.