The Hebrew title of this exhibition, Bal Tashchit, resonates with an imperiousness that shudders through the English translation with equivalent thunder. It's hard to imagine disavowal of this command inspiring anything but an unforgiving finality, as the excerpt from Ecclesiastes 7:13 attests, 'When God created the first man, God took him around to all the trees in the Garden of Eden and said to him: See my handiwork, how beautiful and choice they are& be careful not to ruin and destroy my world, for if you do, there is no one to repair it after you'.

Taking its point of departure from ancient writings in the Torah or the Bible, curators Melissa Amore and Ashley Crawford have placed fourteen contemporary artists (both Jewish and not Jewish) into an exhibition that hitches on earthly destruction, and links the current climate of environmental degradation with ancient precepts and prophecies of doom from rabbinic texts.

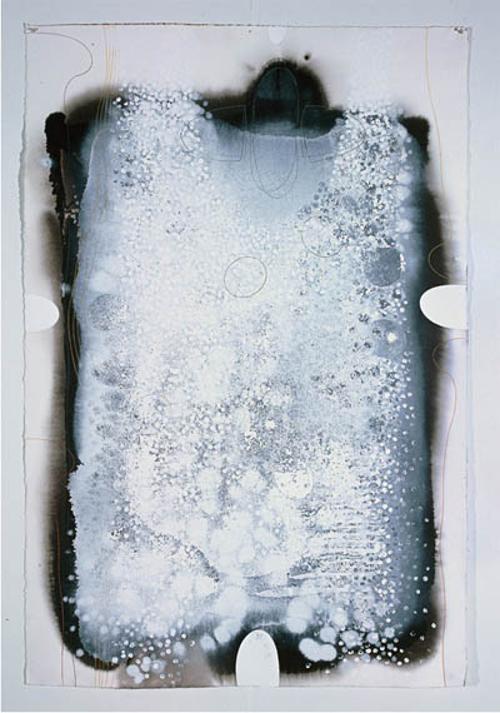

Each of the artists' works is paired with a specific text excerpt, displayed on the wall next to the work. It's a heady mix. The writings offer a dramatic entry point into the works casting them in an arresting new light, and their ecological themes are intensified through this juxtaposition. Irene Hanenbergh's zund-print on aluminium ripples with frenetic motion. The furred figure extends its limbs like some unidentifiable animal in its death throes, and matches the quote from Genesis that speaks of the destruction of 'every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth'. Sam Leach's paintings of dead fowl rendered in the manner of seventeenth century Dutch still life are animated by the portentous text from Jeremiah warning that like a partridge who sits on eggs and hatches them not, he who grows rich by ill means shall 'at his end be a fool'.

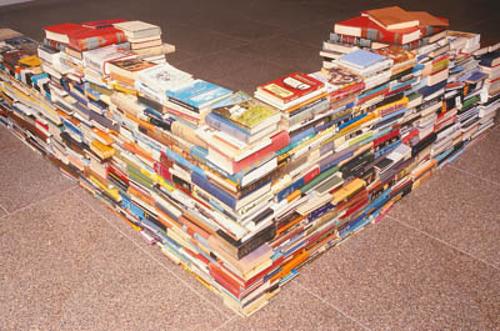

Cultural slippage occurs in certain themes: in Judaism salt is a symbol for preservation, used as the substance that brokered the Covenant between God and the Jews whereas in current ecology salination is the marker of severely degraded land. Lauren Berkowitz's floor installation sets the edible substances of salt, seeds and pulses into wave-like lines that pay homage to Bridget Riley's iconic Op painting of the mid-1960s. Yet its warm tones and the flowing lines of their arrangement evoke a land of milk and honey, not the catastrophe of dryland salinity that affects huge swathes of Australia's arable land.

While it is an almost daily occurrence to read of the impending death of the Murray-Darling basin or the increased number of threatened species, many of the works eschew topical concerns. Instead of presenting overt agitprop the exhibition is suffused with a sense of lingering malaise. However, the strongest works have internalised environmental awareness, and although enlivened by their texts, generate their own potent sense of doomwatch.

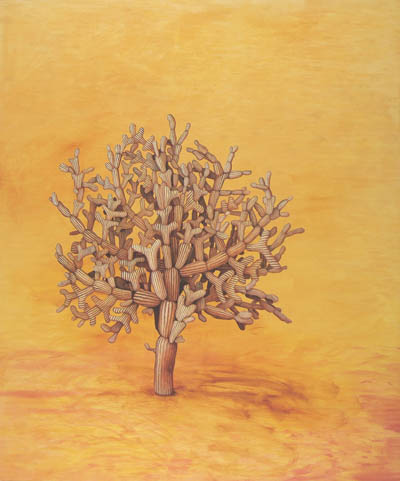

Vera Möller's small fungus-like organisms sculpted from modelling material simultaneously suggest barrenness and fecundity. Their leafless forms herald a dystopia of genetically engineered plant life; trees mutated into travesties of their antecedents. Similarly, Mikala Dwyer's plastic-sheathed trees sport fruitless branches. In the context of the exhibition both artists' works glow with new levels of eerie portent.

Pat Brassington's digital print of a submerged masked figure, half-woman half-fish, is even more powerfully dystopic. The ocean and the swimmer are both rendered in murky greys, connoting the horror of irreparable contamination: ocean defiled beyond repair into a ghastly slurry. The image perfectly conjured for me the post-apocalyptic vision of Cormac McCarthy's The Road. In this unflinchingly bleak novel of the aftermath of environmental catastrophe a father and son walk a cauterised earth in the hope of finding a place untouched by devastation. They trudge southwards towards the coast but when they finally reach it their worst fears of the pervasiveness are confirmed. The ocean is no longer blue but ashen and dead, 'a heaving vat of slag'.

The most obvious curatorial omission in Bal Tashchit is artist Susan Norrie, whose long-standing focus on environmental catastrophe would have sat squarely within the exhibition's premise. Although the inclusion of Kathy Temin, whose work is more generally focused on popular culture and domestic banality, seemed incongruous, her commissioned work unexpectedly summed up the exhibition. Situated near the exit, a large boxy object in the form of two abutted rectangles covered in green fake fur like a giant green mattress, the work served to imply that, environmentally speaking, we have made our bed and now we must lie in it.