This book is a superb object, no expense has been spared in its making. It contains 235 full page reproductions of, to quote the press release, 'iconic photographs of churches, marae, cemeteries, Masonic lodges and other subjects'. Aberhart is a virtuoso photographer who has worked consistently at his craft for almost thirty years, has works in collections around the world and has received many awards and much recognition.

The two essays by New Zealand-based curator and writer Justin Paton and curator, poet and painter Gregory O'Brien are rich, warm and reflective, each includes memorable personal anecdotes as well as placing Aberhart firmly in a canon of the best photographers in the world.

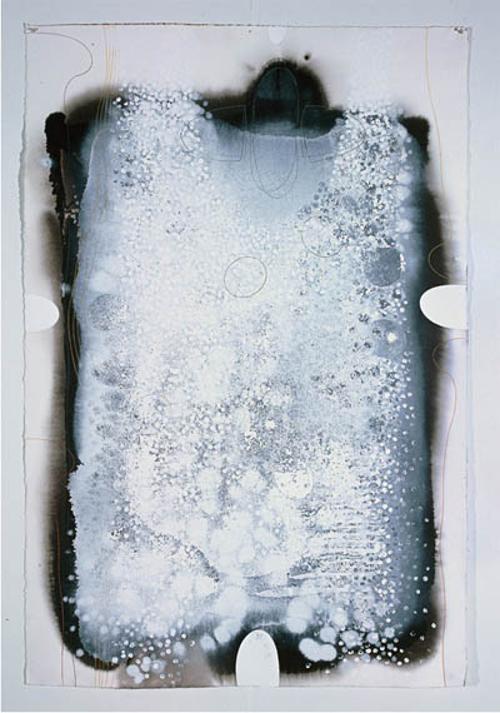

Yet at the heart of the book is a sense of mystery. But perhaps that mystery is an important part of Aberhart's photographs and is what gives them their strength as much as his consummate expertise in the field with the century-old Korona 8 x 10 view camera he favours and in the darkroom where he tones his black and white photographs with gold and/or selenium toners. The inseparable nature of content and form is here made explicitly manifest. There is something very old-fashioned about Aberhart's practice, his photos often look as if they were made a long time ago and indeed consistently use the mineral-rich materials and the long exposures of early photography.

'Churches, marae, cemeteries, Masonic lodges, landscapes and other subjects'. In 1982 Aberhart received an Arts Council grant and used it to photograph Maori churches in the northernmost region of New Zealand, a place called Northland. As recently as February 2008 he showed a series of forty-two photos titled Northland Maori Churches at Darren Knight Gallery in Sydney. In Aberhart's artist's statement for the show he explains the origin and history of these photos which includes the storing of the silver gelatine negatives for more than twenty years while what he calls the 'Maori Renaissance' made it necessary for a European (a Pakeha) to stay away from Maori culture in any form.

Now in his fifty-ninth year and after his major survey exhibition at the City Gallery Wellington in 2007 for which this book was compiled Aberhart is re-entering his files of negatives and discovering that 'Time is running out and what has not been printed may never be.' His primary project has been to print in its entirety, the Maori Churches of Northland.

Aberhart photographed, and photographs, both the inside and the outside of these churches and the quietness which predominates in their simple austere architecture, what O'Brien calls 'architecture that withholds rather than projects meaning'. Aberhart's eye and his aesthetic are largely about a combination of light and strangeness. People rarely appear in his works, but it is the empty buildings made and used by people and the signs put up by them, the words left by humans, the spaces filled with light and worn or spartan furniture that show him to be a social historian of subtlety and depth.

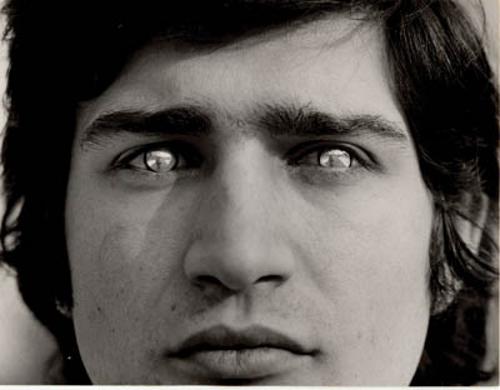

The man himself is nowhere to be seen and we learn little about him or his life. Paton's essay does deal with the few photos in the book in which people appear among them images of Aberhart's children when young and states that the artist has said, in an echo of the idea that photography can steal your soul, that he is afraid of photography's capacity to 'carry an image of somebody that is not a real representation of them'.

Aberhart has taken photographs in other countries besides New Zealnd such as Australia, the US, Macau, Europe and Japan. His photos of other places contain an aesthetic and subject matter, an attention to the vernacular, that is Aberhartian. For example in Dimboola in 1997 he took an image of a car dealer's abandoned yard with old signs reading Torana, Holden, Monaro, behind which a spotty flat scratchy lawn stretches to a corrugated iron fence.

Yet what makes his photographs memorable and more than memorable, in fact sometimes almost like spirit photographs which seem to have always existed, which document the world and use the indexical qualities of his medium to record and fix a view, an angle, a building, a sign, a room, is, for this viewer anyway, that he shows us New Zealand, a legendary place with a forceful indigenous population, a tough European population, an extraordinary landscape, a place of isolation and religious fervour, a place where the air is full of light and all human culture rests provisionally, lightly, on the earth.