God Help Us ...to stay true to the meaning of the work! It seems wise to start off with an invocation, a mantra or at least a benediction before embarking on a response to Western Australian artist Rodney Glick's latest offering at the Lawrence Wilson Gallery. In true Glick spirit God-favoured, in which we encounter some of the last fifteen years of his extraordinary output, branches out into all sorts of esoteric wanderings so some divine guidance might not go astray.

This retrospective, as good retrospectives should, puts Glick's practice into perspective without being too pedantic. (Is giving away the whole story possible when so much of the work is wrapped up in mythologies?) God-favoured maps, or perhaps charts would be a better word, the variant courses of Glick's journeys. In fact it's great to see quite clearly the confidence with which Glick follows something that's piqued his interest and the fervour with which he engages in new experiences. Pursuing the chance occurrences; because as Borges says: 'there is no such thing as chance, only misunderstood causality', is ultimately what brings so much energy and freshness to his work. The underlying strategy, if there is one, to all these encounters is the open honesty with which Glick questions art's perceived operating systems.

There are far too many projections, sculptures, photographs and publications to cover here so I'm going to concentrate on two works, both coincidentally in the back corner of the Lawrence Wilson Gallery, which I think best exemplify Glick's modus operandi.

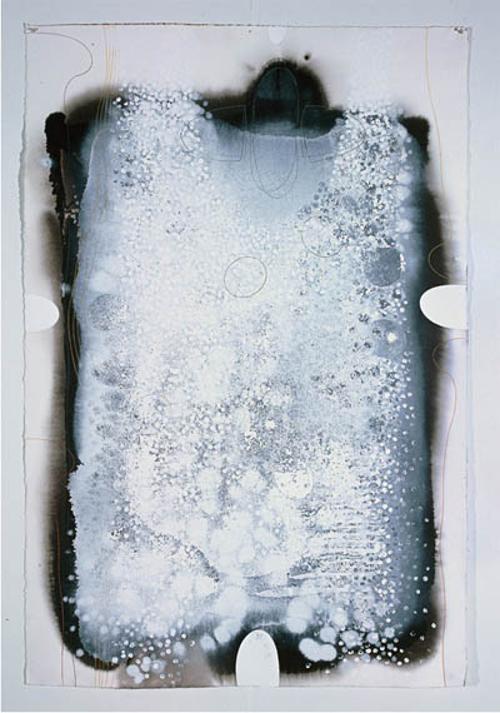

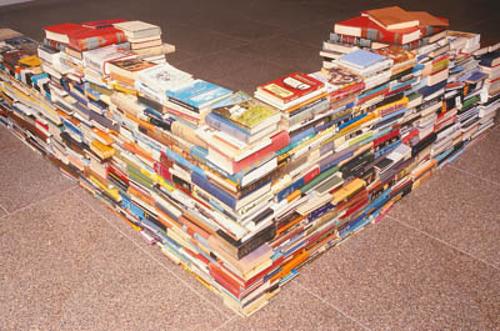

Master of Prayer and Joe Binsky's Tree of Life both hone in on the nature of systems and their influence on our lives. Both works do this through Glick's links with Judaism. Joe Binsky was a Jewish man whom Glick and David Solomon (his friend and sometime collaborator) met some years ago. Only when they investigated his home and his life a little further did they find that he had fabricated his whole family and further to this he had falsified their experiences and communications with him. Of obvious interest to Glick, who has fabricated more then his fair share of stories within his art practice, Joe Binsky becomes, in the artist's eyes, a kind of mythical figure himself and Joe Binsky's Tree of Life, a shrine to the power of myth-making.

On one level this encounter critiques obvious crossovers between arts practice and life, but as with all Glick's work there's plenty more going on. Joe Binsky's Tree of Life, that basis of all knowledge, more interestingly questions how we know what we come to believe in. Our world is dominated by certain behavioural systems like law, doctrine, intent, social expectations, but where do these systems come from, what are they built upon and what happens when they break down? In this sense universal constructs impinge directly on the expectations of personal life outcomes, they can also make us feel very lonely when either they or we disintegrate.

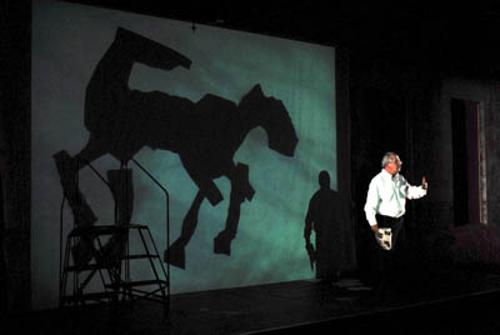

Master of Prayer takes as its point of departure the Shmona Esrei, a Jewish benediction or responsorial prayer. In this work, one computer leads the prayer and nine others answer in chorus, it's very seductive and meditative. On one level we are reminded of the artificial intelligence we have created and its drive for spirituality (which must be inherent in its structure because we created it, right?) but the issues keep tumbling out of this one too. Inherent in the work is the clash between personal freedom and universal structures, between faith and science, between right behaviour and automated response.

These clashes arise again and again, for example Glick's new multi-armed carved wood sculptures reminded me of the recent case of the Indian girl born with many limbs and the fight over her body engaged in by medical science and religion. Glick's work at times feels laidback and relaxed but the more you delve into it the more complex and enigmatic it becomes. Such is the way of the guru and the artlife of the bodhisattva Glick.