Artlink's June issue clearly demonstrated the flexible nature of the historical record, especially how personal stratagems harden into the cultural and historical certainties that drive debate at a national level and indelibly mark professional and popular consciousness of Australian identity and character.

On the one hand we were offered a positive, upbeat, perhaps even hagiographic, review ('The Queen can do no wrong' - as Rudyard Kipling once said - that is temporal power begets cultural authority) of the latest book by possibly the most titanic and central name in writing on Australian art, Bernard Smith. In a marvellous juxtaposition, a personal memoir by Donald Brook published in the same issue outlined in a calm and professional manner the fraught recollections of working alongside an Australian icon. The dialectics of the polarised viewpoints represented by these two articles expose the mutability of reputation and the clear role that personality and interpersonal relations play in this.

In Australian cultural narrative there is a de facto erasure. Often the evidence of non-mainstream practice has been scattered without any attempt at preservation and capture. Concurrently the opportunities for publishing and disseminating stories in a professional and high profiled manner are carefully controlled.

Partly too, the current tendency in Australian cultural industries to place history writing as the dead Other to the live world of practice. Making (unless it is the narcissistic scrutiny of individual makers), suppresses curiosity about different and untold stories. The belief that history is irrelevant to the virtuous activities of doing and making (four legs good two legs bad) also fosters a complacent belief that Australian heritage specialists - galleries, museums and universities have got a handle on 'the stories' and are doing the right thing full stop.

Yet as in the June Artlink, sometimes the processes and inconsistencies of this highly ordered and ranked - think of Versailles and the Forbidden City with its colour coded Dragon Robes - world of storytelling are occasionally exposed.

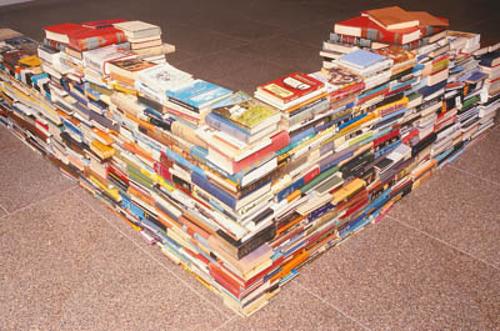

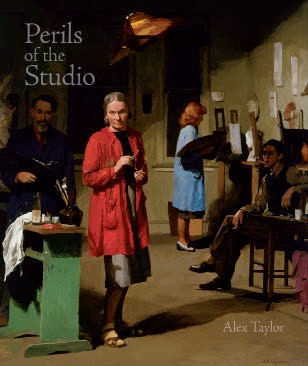

Thus in 'Perils of the Studio', Alex Taylor's historical survey of Melbourne artmaking of the first half of the twentieth century, the source material, whilst not thrown out or destroyed, has slipped out of dominant strands of public memory. The graphics and texts - including a large portfolio of generally bad, but entertaining, fiction about Australian artists - have been sitting unnoticed in long runs of newspapers and journals in libraries. The artworks have more often been in gallery storerooms rather than on display for the best past of half a century.

The core merit of Taylor's book is the anthologising and representing of this material in a format that makes it understandable for a present day audience and also highlights its relationship to current professional concerns. He takes a broad sweep of visual and textual material from high art to popular culture that reflects a consciousness of the 'artist' and 'art practice' as understood in Melbourne/Australia from the period roughly 1900-1945. Additionally there are links back to the late nineteenth century and forward to Richard Florida's highly influential twenty first century construct of the 'Creative Class' and the contribution of lateral thinking 'creatives' to fermenting regional economic development. Whilst arguments about artists' ability to foster social and economic structures that benefit the broader community and the positive role that creativity plays in shaping a buoyant and vibrant society are assumed to be of recent date, Taylor demonstrates that artists in Australia thought about art as a group and cumulative process, which generated cultural capital three or four generations before these ideas became commonplace.

'Perils of the Studio' fills in the Melbourne picture alongside the more established narrative of Sydney as the birthplace of modernism and professionalism in the arts, although there are also cross references to figures such as the Lindsays, who moved from Melbourne to Sydney and Sydney based artists such as George Taylor, George Lambert and Douglas Dundas. This citation of material from outside Melbourne is not always flagged for non-professional readers, who may assume that these figures were active in a Melbourne context, even given the heavy emphasis in the publication as a documentation of place in Melbourne.

Historians have found it easy to work with the clear on-paper documentation generated by the careers of influential and highly organised Sydney figures such as Sidney Ure Smith and Margaret Preston. Bernard Smith's 'Place Taste and Tradition' (1946) and Daniel Thomas's personal networking at the Art Gallery of New South Wales with remaining survivors of Sydney's 1930s modernist scene, have also rendered the Sydney side of the story more tangible than the scattered and diverse records of Melbourne artmaking.

'Perils of the Studio' covers vast swathes of Melbourne-centric material that has rarely been seen in recent times. There is perhaps a calculating strategic-ness in the manner in which the book pegs out a vast range of territory for its author - perhaps the only unpleasant aspect of the book - but happily Taylor lets this material speak for itself. Also there are other projects that could have been encompassed in the research. At least one art theorist/historian, Jonathan Watkins, knew about the frequent visual and textual exploration of the artist's role and lifestyle in such sources as the 'Bulletin' and the 'Lone Hand', and wrote a lengthy Masters thesis at the University of Sydney two decades ago around much of the material featured in 'Perils of the Studio', although his interests changed and he published relatively little from the thesis.

A more recent link that perhaps would have enhanced the final chapter which discusses the current Melbourne scene would have been the catalogue to the important survey of Melbourne ARI's (Artist-run-initiatives) 'Pitch Your Own Tent', Monash University Museum of Art 2005. Mentioning this overview would have indicated that other scholars have touched upon kindred themes. The remarkable innovative work of Mary Eagle and Jan Minchin on the range of pupils of George Bell, famous to unknown, professional to amateur, which was one of the first Australian texts to suggest that an art movement's reputation did not only rest on the stellar figureheads and auction room favourites, is acknowledged however.

Taylor's opposition of architectural historians as formalist pedants to more broad-minded art historians in the last chapter is a slightly irritating argument as it involves thirty-year-old paradigms. Architectural history has changed and is now frequently concerned with the value adding that artistic activities proffer to sites, when considering issues of spatiality, usage, reputation, urban amenity, and the collective and cumulative potential of intangible memories/activities. It is now recognised that these factors, as well as the formalist value of the architecture, render a site significant and also that meaning is generated by the interaction of multiple factors at a given site.

Today's ARI is, as Taylor notes, the natural heir to the bohemian studio of the past. In constantly foregrounding the idea of artists' agency, at both a collective and an individual level, and also the importance of the visible, observed gesture, to communicate an identity as an 'artist', again at both an individual and at a group level, the continuity between present and past lies at the heart of this publication. Max Meldrum's and George Bell's teaching studios and groups such as the Melbourne Society of Women Painters and Sculptors founded in 1901 are not dismissed as curiosities beneath consideration, but reframed as earlier iterations of the facilities that artists still organise. 'Perils of the Studio' examines the prehistory of how artists have thought around the identity of the artmaker, the expectations of practice and the psychological and symbolical complexities of making art in settler Australia.

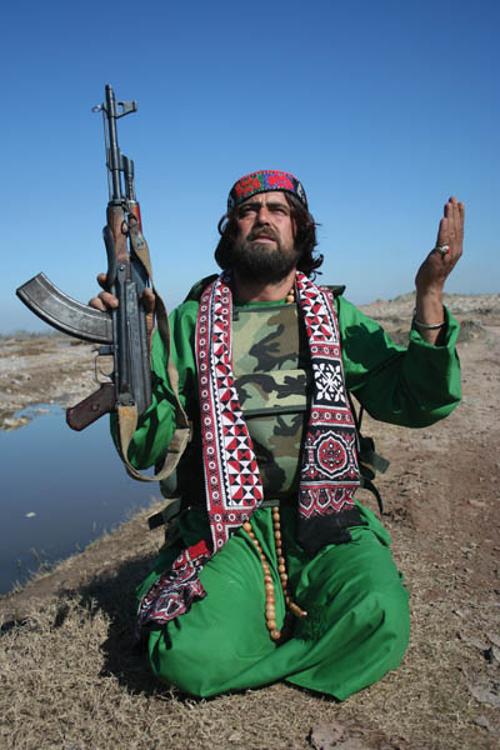

The illustrations, especially the collection of sometimes compelling, sometimes hilarious, self portraits and other images of artists, indicate how gestures and self styling of early and mid twentieth century artists were as politically inflected as any Cindy Sherman photograph. The images, both painted and photographic, generated around the inner city ménage of Archibald and Amalie Colquhoun particularly stand out, including a photograph where - whilst Amalie is cooking under the approving eye of her husband - the fact that she is wearing slacks and frying sausages over a spirit heater in the middle of a bare floor renders her a less than perfect postwar housewife.

Taylor's compilation also indicates how hitherto obscure paintings disseminate intense and conscious agendas and resonate with debates about gender and identity in Australian culture. The opposition of the sportsman and the soldier to the effete, decadent, city-dwelling artist is particularly fascinating and indicates how a concept of art has threaded through the discourses of white Australian normality as a feared Other. Art and those who make it have been imaged as cosmopolitan, shifting, ambiguous, proudly and unredeemably Un-Australian, or else they have consciously cultivated the persona of a direct man of action, and particularly the patriarch of the landed gentry. If Taylor suggests that there are precursors to modern practices in the past, we may also find that the old Victorian romance about the studio as the wild, yet enchanted, space and idealisation of the artists' perquisite of a life lived more vibrantly than that of the ordinary person persist through such publications as the writings of Drusilla Modjeska beloved of suburban book groups and the portentous 'Untitled: Portraits of Australian Artists' by Sonia Payes published last year by Macmillan, not to mention the fatuous Sirens.

Taylor's arguments frequently move beyond the old modernist polarities and, whilst he does not take on the insidious self promotion of the Angry Penguins and the Antipodean groups, which spread the self-glorifying fiction that Australian culture went into deep freeze between the Heidelberg School and the Reeds, not to mention the Whitlam generation's thorough colonisation of the public space for their own glorification, he does take explicit aim at 'From Deserts the Prophets Come', a text that is as iconic in its positivist sweep and its dismissal of culture beyond the radical nationalist paradigms as the histories of Bernard Smith, James Gleeson and Robert Hughes.