Julie Dowling's paintings are a complex montage of indigenous motifs and techniques, along with an assortment of Western art traditions from Pop art to Renaissance devotional references. However, as the recent survey of Dowling's portraits demonstrates, such disparate parts don't always create a comfortable whole. Instead they enable us to see Dowling's subjects in a different light, and ask us to question in whose interests it is for history to be understood in a particular way, and who misses out.

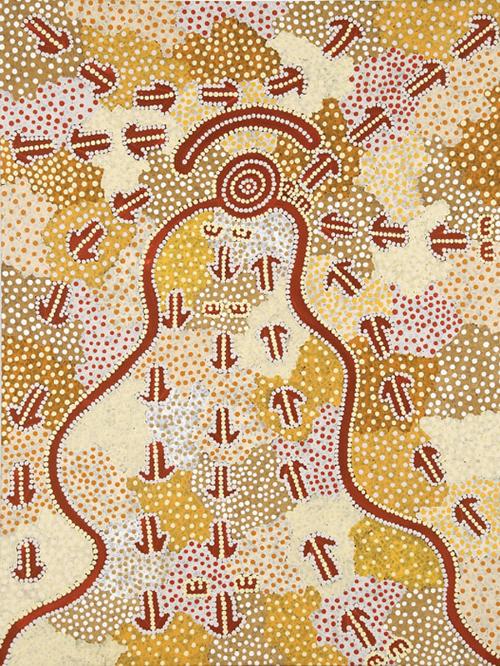

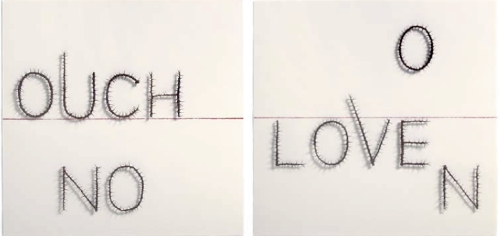

Dowling is interested in re-reading Aboriginal history in order to draw attention to unknown histories and to recontextualise existing ones. Melbin is a large portrait of Dowling's great-great-grandmother who was exhibited around England as a 'Savage Queen' in the late nineteenth Century. Melbin sits in a billowing Victorian gown of rich maroon, surrounded by a vast halo. Despite her regal appearance, the identity tag on her wrist and the motif of manacles within the halo are reminders of the tragic reality of her fate. The composition exposes the tremendous irony inherent in the British Empire's colonial concepts of savagery, nobility and royal patronage. In the Icon to a stolen child series, Dowling has painted the young faces of the victims of the stolen generation as saintly icons, replete with halos and wings that are, in turn, composed of dots in the manner of Papunya or Yuendumu traditions. These children have faces but no bodies. Their limbless torsos look like uprooted tombstones and their impassive faces express nothing of their suffering.

While she might cast her family and other Aboriginal figures as legends, martyrs and saints, Dowling does so in such an explicit fashion that she is the first to acknowledge that any history, even her own revised history, has its prejudices. As Melbin and the I object series (a reappropriation of 'ethnographic' photographs) suggest, conventional documentation is as unreliable as memory and folklore. However, it is a fairly basic postmodern statement to express suspicion about any singular claim to authenticity and it always begs the question what, apart from nihilism, do you propose instead? In Dowling's case, her portraits rescue her family and cultural heritage from ageing photographs and the confines of official history, giving them a fantastic emancipation in the minds of those who both remember and imagine them.

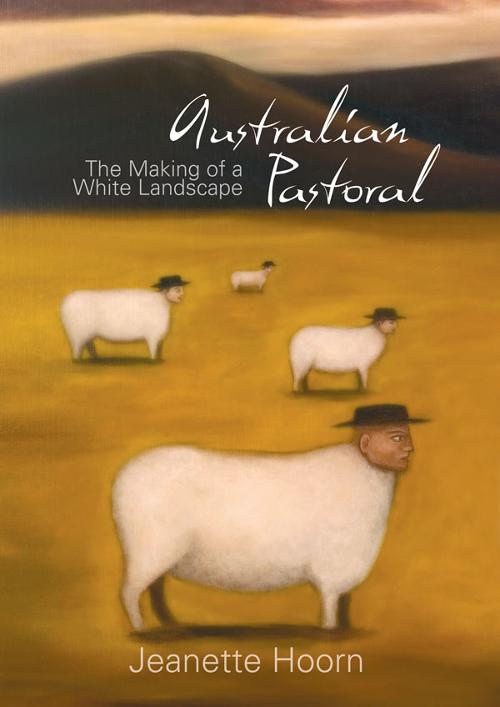

Referencing Billie Holiday's rendition of the song Strange Fruit, curator Jeanette Hoorn positions Dowling in a larger context of psychoanalytic theories to do with witnessing, testimony and the trauma of racism. It's also worth mentioning Brenda Croft's 1994 exhibition and photographic series, both titled Strange Fruit, which evoked the notion of sectioning people along racial lines and the struggles to fit into this stratification. This notion seems to surface in Dowling's many self-portraits and family portraits, and also in narrative paintings like Bloodlines (2003) where the outcast children of mixed-race parents have been relegated to mere workers. By linking Dowling's own history to national and global considerations of persecution and racism, the exhibition is a potent reminder that the personal is irrevocably, irresistibly political.