''The Hours' has not only given us a chance to contemplate recent Latin American art, but also to reflect on the ongoing debates about the function of art, whether its value should be tied first and foremost to its ability ''to be art'' or to provide recognizable displays of moral-political didacticism. The exhibition is presented by the curator, Sebastian Lopez, using ''time'' as an orienting theme/frame. The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges has been chosen as interpretive key or intertextual voice (sound-box) with which to meditate on the 'Latin American experience of time and history''. Lopez wishes to avoid the charge that ''this way of grouping works may give the impression of being the only one possible'' and is obviously aware that ''works of art cannot easily be reduced to only one or two readings''. No doubt, but many of these works cannot be adequately appreciated without taking into account the specific, very real temporal and political contexts in which they were generated, rather than the kind of detached philosophical meditations on time found in Borges.

Many of the artworks are a very clear staging of time and violence and gesture towards a ''freezing'' of time – the interregnum before redemption from violence, a redemption which may never come. Borges, on the other hand, was renowned for his ''fascination'' with violence. Where perhaps a valid link ''might be made'' is in the quotation around the walls of part of the exhibition which refers to the old gaucho from Borges's short story ''The South'', a figure from a traditional culture. In the story, the gaucho is old and outside time, shriveled up, swept aside by modernity. There is only a cipher left, a hollow representation of the past. But the historical referents which underpin the artworks on display in ''The Hours''-here the past of state violence, in particular - have not been swept aside, but wait, tenuously hanging on in the form of artistic memory, which attempts to evoke the very real experiential memory of the victims.

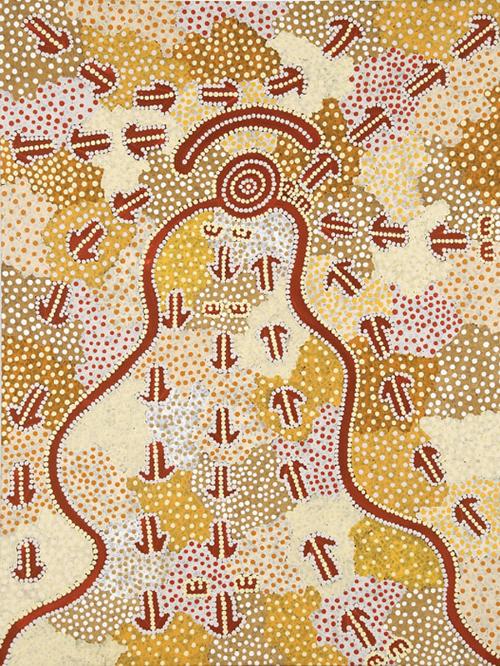

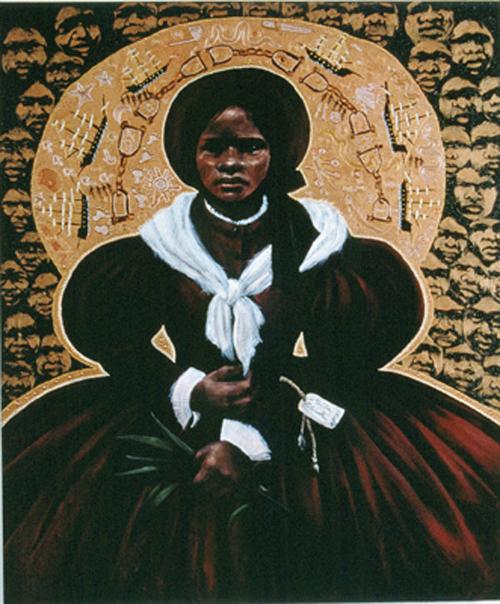

This waiting game is registered in the simplicity of the indigenous world evoked in Maruch Santiz Gomez's linking of photos of everyday objects and often humorous aphorisms from indigenous quotidian existence, and José Alejandro Restrepo's tribute to black Colombians in ''Song of Death''. Nicola Constantino, on the other hand, works with the dialectic of near and far. As we move closer to view her fashion statements in clothing, shoes and handbags (there is even a football), we are jolted as we realise they are made of what looks like human skin.

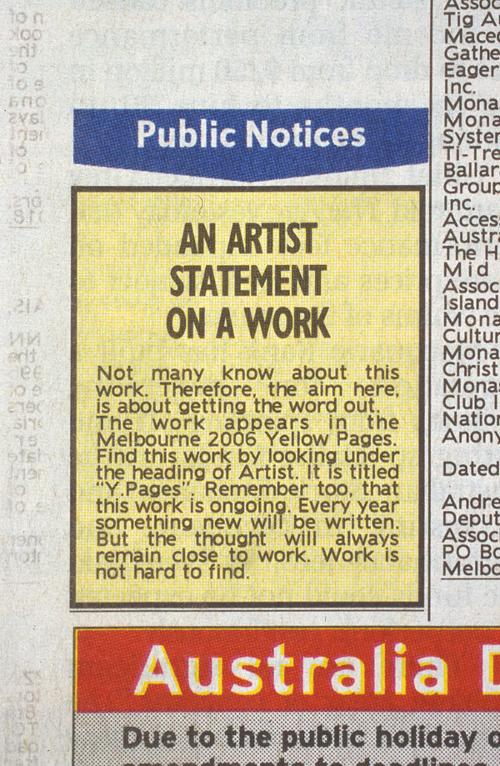

Alfredo Jaar''s ''A Logo for America'', a one-minute video ''statement'' against the monopolization, in effect the symbolic violence, of the word ''America'' by the United States, was originally shown 20 years ago in Time Square, New York. The work belongs to a virtual tradition of artistic statements through both Latino music culture, the Panamanian singer Ruben Blades 'Buscando America'' (Searching for America) and Trini Lopez''s 1960s tune 'America', to some contemporary Latino intellectuals, all longingly waiting for an inclusive vision of America through common appropriation of the name. Wilfred Prieto, on the other hand, presents photos of a series of flags with colours reduced to shades of grey and aligned in democratic fashion, suggesting the artificiality of symbolic conventions and the need to ''put flags in their place''.

Nadin Ospina ironically quotes the Walt Disney version of the world with the mock, pre-Columbian artefacts superimposed with cartoon character heads. It is clever, it is obviously political in its criticism of the commodifying push of capitalist modernity, but does it function as art or merely as propaganda? In other words, is it just a ''one-trick pony'' or does it live on in subsequent multiple interpretations, as open artworks should?

Many of the works in ''The Hours'' utilise kitsch and mundane everyday objects. In ''The Annunciation'', Dario Escobar cleverly reveals two versions of the biblical scene painted on the inside of a sleeping bag, a most prosaic and contemporary representation, alluding both to the activity of lying down to sleep, but also, it seems, having sex. Vik Muniz renders canonical artworks, photos and people from both high and popular culture, with wire, thread, syrup, food and dust to question the problem of illusion and the copy.

Some of the works which link time and violence require some contextual knowledge to fully come alive in their interpretive possibilities. They are among the most satisfying in the exhibition. Oscar Munoz, like Muniz, is a kind of ''illusionist'', but with a much darker ''message''. In ''Aliento'' (Breath), he has polished small steel discs to mirror-like smoothness on which is an oily imprint of photos of people, which faintly appear when breathed upon. In an act of transmutation, your self-reflection is suddenly replaced with the face of a victim of Colombian violence. Lazaro Saavedra''s ''Suspended Knives'' are fascinating for their interactivity beyond mere contemplation since the viewer feels a chill at the thought of walking beneath them. The knives are clinically arranged in a strict grid pattern, suggesting a sinister rationalisation of violence, and are encased in the claustrophobic space of a windowless black cubicle, the entire scene gesturing towards the fear under which many people in Latin America live on a daily basis.

Doris Salcedo''s chairs are fused in an unnatural pose, the remnants of a violent act, namely the attack twenty years ago on the Justice Building in Bogotá by the Colombian armed forces intent on liberating hostages held by a Marxist guerrilla group. The ensuing attack left most of the hostages dead and the destruction of the building. In Salcedo''s stark memorialisation, sets of ashen-coloured chairs are set off from one another in seemingly random pattern, or convolutedly stacked, suggesting anomie but also solitude, irrationality and tragedy. Betsabee Romero works with old cars and car tyres: the automobile as a symbol of US modernity, but also its paraphrase and re-functioning within Chicano ''low-rider'' car culture. Her works involve crafted art objects which are then photographed in situ as part of a much larger and more complex framing. In ''Requiem for the unknown pedestrian'', Romero presents a series of car tyres etched with differing patterns which have been printed on to a canvas in the form of a quasi-musical score perhaps to honour the pedestrian dead or simply the pedestrian overshadowed by a technological culture massively over-determined by the automobile. The tyres are aligned choir-like in front of the score, as if to signal the gravity of the scene, but also its perversity.

The exiled Cuban, Manuel Pina, has photographed the sea looking out from the Cuban coastline. The tight cropping of the upper portion of the black and white photos (the sky) creates a feeling of tension and claustrophobia juxtaposed to an overwhelming and wide sea, which seems to point to the sea as both limit of the (now colourless?) Cuban Revolution, but also as a promise of freedom (the passage across the Florida Strait). A young boy is suspended in a dive towards the open expanse of the water. Where to Cuba?

This exhibition reminds us of two things: that Latin American art is alive and well; and that it is often intensely political.