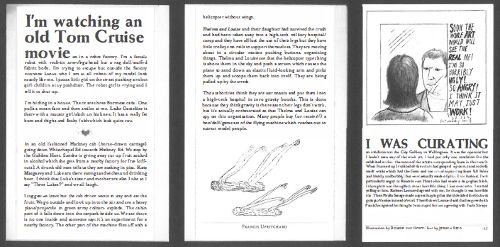

Since 1995, Contemporary Art Services Tasmania's (CAST) Emerging Curator Program has created a number of outstanding exhibitions while providing a nurturing platform for young curators to spread their wings. In a state that can suffer from cultural isolation, mentorship programs like these provide an essential lifeline to arts practitioners looking to broaden their skills and make Tasmania their base.

Corrupting Youth, a confronting selection of work by emerging Tasmanian artists, was the culmination of the 2005 mentorship undertaken by Tristan Stowards. Bringing together photography, stencil art, painting, sculpture and video, Stowards explored the youthful underbelly of sex, intimacy and consumer culture and stripped back our expectations of private and public space.

The strongest inclusion in the exhibition was Melanie Breen's commanding series of five photographic portraits depicting children watching television. Seated alone in a darkened room, their faces illuminated by the glow of the screen, Breen's subjects were enraptured by movies like Finding Nemo, Peter Pan and The Wiggles. Capturing the kids with their mouths agape and small hands clasped in mute anticipation, Breen's portraits were imbued with a shadowy vulnerability as the act of unadulterated worship was frozen in time and displayed for public viewing.

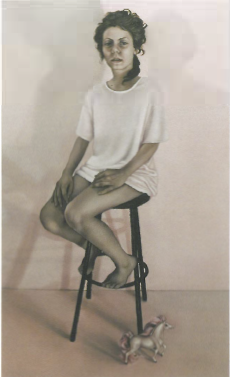

Annika Koops, a painter whose work is whittling her a place amongst Tasmania's most promising young artists, was represented by two complementary oil paintings of supple-skinned girls. Drenched in soft hues of pale green and rose pink, Koops' seductive half-dressed subjects gazed expectantly at the viewer, exuding a youthful femininity spiked with defiance. While Koops' technical skill is clearly evident in the recording of meticulous detail, these works were cold in their slickness, the subjects unwelcoming – a considerable change from the deeply lush, surreal figures seen in earlier work.

Amongst the rising number of artists drawing inspiration from stencil and graffiti art is Hobart based Tom O'Hern (a.k.a. Empire). Creating the largest work in the exhibition, O'Hern stencilled an orgasmic conglomeration of sexy pop imagery peppered with skeletons, cartoon birds and gun-yielding boys onto the back wall of the gallery. Drawing the viewer in with its vertiginous composition, the inclusion of O'Hern's work signals the growing significance of street art and its importance as a creative vehicle for personal and social commentary.

The most confronting work in Corrupting Youth was Lauren Olney's Beautiful Agony (2006). Projected in a separate room were a series of home videos displaying the determined faces of people reaching orgasm. Similar to the contributions displayed on the website of the same name (each video was produced by the participant rather than Olney), Beautiful Agony blurred the distinction between public and private performance. Preceded by a warning sign and dramatically ascending moans, Olney's intimate tapestry was heard before it was seen and at times this detracted attention from other, equally worthy works.

In a homage to Marina Abramovic's performance piece Rhythm O (1974), Jane Tyler's family of plaster cast human torsoes hung like tortured remains on the gallery wall. Evolving over two years, the torsoes were initially displayed in a pub during the 2004 Tasmanian Living Artists Week where Tyler invited patrons to deface the powdery surface of the limbless forms. The final work, complete with scrawled insults and toilet door smut, accentuated the disturbingly powerless nature of the body and lack of audience restraint. I wondered if the defacers would crayon their name over the living flesh of a child's bare stomach or the yielding tissue of a real breast.

Ultimately, Corrupting Youth was a patchy exhibition with promising yet diluted themes. The catalogue essay provided by Stowards expanded on the included artists' work in illuminating detail yet the media release sent out mixed ideas. The strength of the exhibition was its ability to bring challenging work by local artists to a wider audience and offer a fresh insight into the contemporary struggle for identity, acceptance and security. Corrupting Youth could have been a tighter package but it was nevertheless a good start.