Can anyone remember how Matilda the giant kangaroo trundled around the track at the opening of the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games, turned her head, leered, winked and finally stopped to disgorge a horde of school-children dressed as joeys whilst a long suffering choir sang endless reprises of Click Goes the Shears. Since then the Commonwealth Games' pig-out on Olympic Babylon fever has delivered not only an ever-inflating spiral of more portentous opening ceremonies and an overdose of media and governmental rhetoric about the Australian spirit, but also a serious cultural program within the hyperbolic compounding competitiveness.

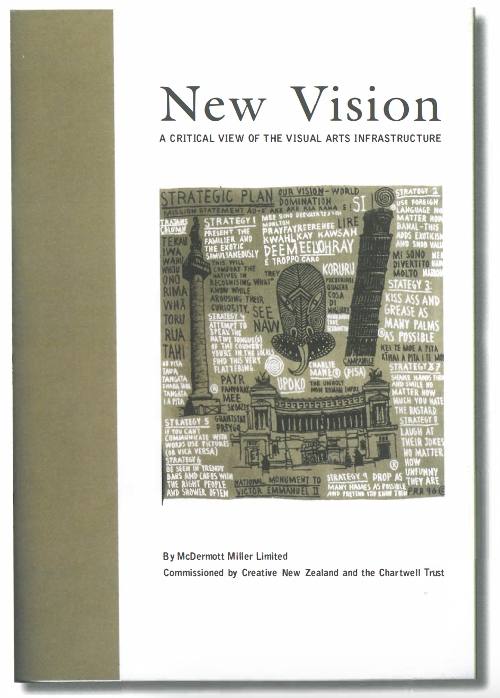

Juxtaposing the despicable Matilda with Festival Melbourne 2006 indicates how far the nature of the visual experience in Australia has shifted. The Festival Melbourne exhibitions tapped into current preoccupations. They explicated negotiations around creativity and identity, the interplay of regional, national and global, tradition versus innovation, ethnicity versus intercultural, craft versus art, natural versus conceptual/educated. They also reflected debates that have been simmering in Australian mainstream media and blogs around the value of art versus craft. A recent Art Monthly salvo critiqued craft for its narcissistic naiveté and self absorption, whilst other writers make claims for craft as a more genuinely democratic, inclusive artform which uniquely facilitates intercultural dialogue and meaningful interchanges.

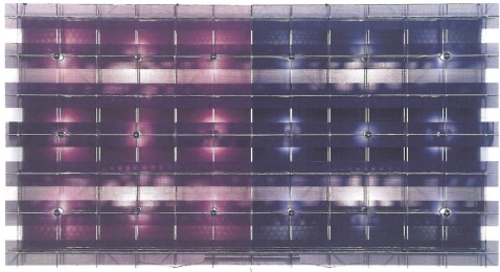

The exhibition Material Goods (Melbourne Museum) took this stance and explicated it through fascinating but tightly orchestrated partnerships between local and overseas makers. In all but one case (an underwhelming local practitioner) the dexterity and sense of design and emotional ingenuity impressed. The charisma of the visual in the everyday was exemplified by the employment of Karachi vehicle decorators to embellish a Melbourne tram, circling the city as an effective and serendipitous cultural exchange.

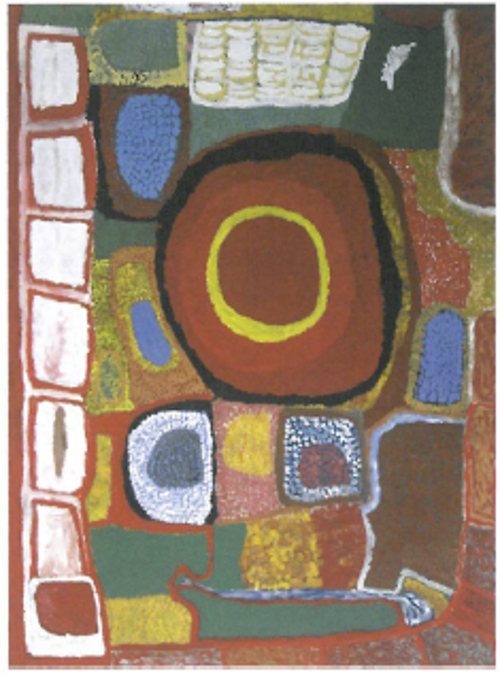

In a Postcolonial era, the term Commonwealth, although nearly blandly inclusive for a polyglot collection of countries, undoubtedly carries the electric charge of its racist foundations in the British Empire. To retrieve something positive from these tainted origins, two guest-curated exhibitions which presented an excellent range of pieces across many cultural traditions, Beaded Links (Counihan Gallery, Brunswick) and Threading the Commonwealth (RMIT Gallery), took an ethnographical approach, indicating how psychological and social functions for making and using cultural products are shared across races and ethnicities. Both celebrated optimistically the skills of the makers, the remarkable technologies behind the exhibits and their compelling formats and surfaces. This approach created a utopian vision of a shamanistic community of skilled practitioners embedded in everyday life, a calm stasis within the more overt politics of exchange, seen in Carve (Melbourne Museum) for example.

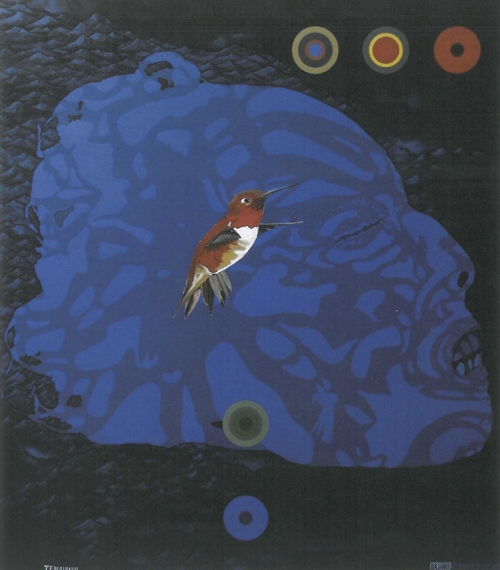

Game On: Sport and Contemporary Art at the Ian Potter Museum of Art took on the 'Games' rather than the 'Commonwealth' and looked at the role of sport in forming identity. Here cultural identity as the force of post-colonial authenticity was compromised by powers greater than the individual. Matthew Greentree unpicked the political and military resonances of massed events like the Commonwealth Games. Roderick Buchanan in Coast to Coast, Dennistoun 1997-2000, offered an extraordinary series of photographs of males in Scotland wearing merchandise of North American baseball teams, amplifying yet obliterating the teams' identities. His lyrical shifting video loops of singing teams and bare-chested embracing players recasts televised sport as a miasmic homoerotic ballet. The male centricity of Game On, where the feminine only appeared through a tortured gymnastics coach's despairing desire in Richard Lewers Skill, Training, Discipline 2005, was challenged by an unofficial revival of Mary Lou Pavlovic's Liar, a work addressing sexual abuse in sport.

Pavlovic issued a lively manifesto criticising the complacency and predictability of official curatorial policies in Melbourne. Part of the volatility and meaning of Festival Melbourne was not its authorised content, but the juxtaposition of incompatible elements, such as the visit of Cook's Endeavor whilst its conceptual dichotomy Camp Sovereignty was erected in the Kings Domain; or the Next Wave festival of emerging artists juxtaposed against the corporate overproduced spectacles of the opening and closing ceremonies which reprised the self-promotion of the Kennett Government and added the faux inclusivity of the worst of community arts. Will someone please tell me what is that thing going on between wealthy, elderly, left wing Melbourne and the bathetic work of Michael Leunig? I still don't get it.