To paraphrase Michel Foucault, in a characteristic moment of poetic hyperbole, the Enlightenment ushered in the unimpeded empire of the gaze. Two hundred odd years later, not much has changed. Sight remains the most privileged of the senses; revered by science and spoiled by art. Even in the twenty-first century, most art is still designed primarily for the eyes. Signs in galleries remind us that we may look but not touch, and the remaining senses – taste, smell, and hearing, don't even rate a mention. In What Survives: Sonic Residues in Breathing Buildings, curator Gail Priest upsets this hierarchy by presenting an exhibition for the ears, hands and eyes, in that order. And a listening room in the men's loo even offers a little odour-ific stimulation for the nose.

As the exhibition title indicates, Priest is positing a relationship between sound and architecture as repositories for memory, a hypothesis in which buildings have the potential to soak up and re-release audio energy. If architectural structures can indeed function as sonic sponges, then Priest has chosen fertile territory. 199 Cleveland Street, Sydney has been continuously occupied by Performance Space for 22 years and must have some intriguing tales to tell. With this in mind the exhibition spills beyond the main gallery spaces, where Alex Davies, Nigel Helyer and Jodi Rose have installations, to listening stations in other unexpected locations.

Alex Davies's installation, Sonic Displacements, most closely embodies Priest's curatorial premise. By placing microphones throughout the gallery, then recording, delaying, mutating and replaying these sounds (snippets of conversation, fragments of traffic, thumps and bumps) the building seems to have an audible stream of consciousness memory or to be haunted by noisy ghosts.

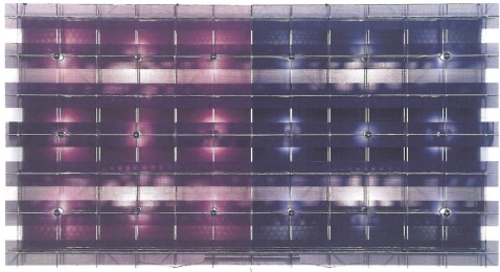

Jodi Rose also uses recordings of ambient noise as raw material. In Playing Bridges a miniature bridge sculpture doubles as a musical instrument. Visitors are invited to play and share in her personal obsession. For ten years Rose has recorded the strange rumblings and rhythmic clangs of bridges all over the world. She translates these noises into strangely haunting and hypnotically seductive sound-scapes.

But it is Nigel Helyer who really captures the irresistible pull of listening, especially listening in. Since mobile phones have become ubiquitous we hear a lot more than we used to. Screaming into their handsets on buses, in the street and everywhere else, people seem to think that along with a handy camera these indispensable bits of technology come equipped with their own individual cones of silence, either that or they just don't care. It takes no effort at all to hear the intimate details of other people's lives. But overhearing isn't quite the same as eavesdropping; a taboo activity that still carries an illicit thrill.

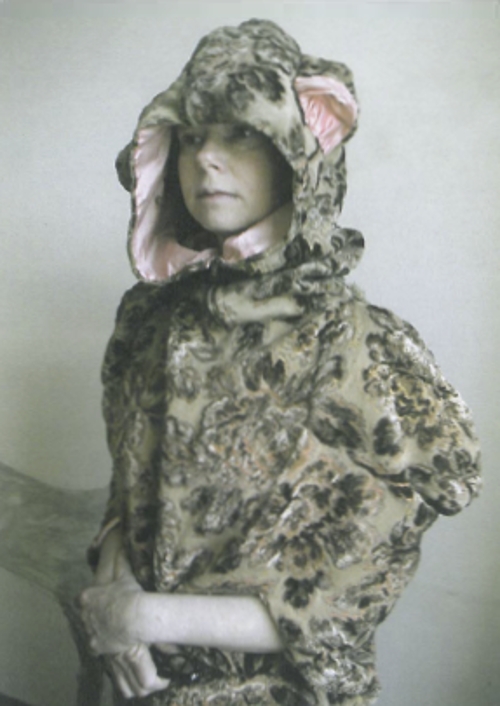

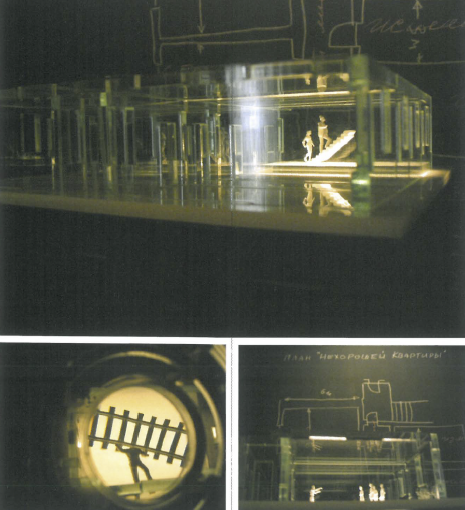

In his installation, the Naughty Apartment, Helyer invites adventurous gallery visitors experience the heady excitement of being an amateur spy. In a darkened space, Helyer has staged strange tableaux acted out by miniscule figures in glowing perspex rooms. The scenes are based on Mikhail Bulgakov's fabulist novel, The Master and Margarita. Wearing headphones and wielding a nifty electronic gadget, complete with built-in magnifying glass, visitors are invited to listen in on the action.

Feeling like the plucky hero of a Boy's Own Adventure, Helyer's installation seems like good, clean, fantasy fun. But it also points to a more sinister reality. We live in a culture of surveillance, one in which any tech-savvy voyeur can walk out of Dick Smith's with enough equipment to get his kicks. And it's not just the weirdo next door who is indulging in a spot of spying; our own government continues to grant itself ever greater powers of listening and watching. Helyer's Naughty Apartment is a reminder that we live in interesting times; our civil rights are being quietly and persistently eroded. In the immortal words of Joseph Heller from Catch 22, 'Just because you're paranoid, doesn't mean they aren't after you.'