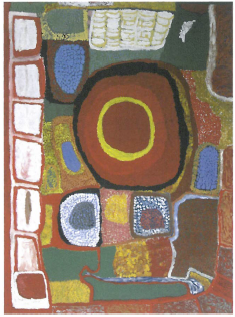

Part of the market allure of Indigenous art from the central desert and top end of Australia has been the fact that it continues an ancient tradition. This fact is not lost on canny art dealers who are better able to catch the interest of inexperienced collectors by alluding to mysterious ritual meaning half hidden by the sands of time than by discussing what makes a good painting. The appeal of the intensely colourful paintings produced by Kaiadilt women from Bentinck Island near the southernmost part of the Gulf of Carpentaria, however, depends on their appearance rather than their ancient spiritual mystique. They did not have a painting culture until last year. This year they have exhibitions all over Australia. Sally Gabori, who at he age of 81 started it all, must be the oldest prodigy ever to emerge in Australian art.

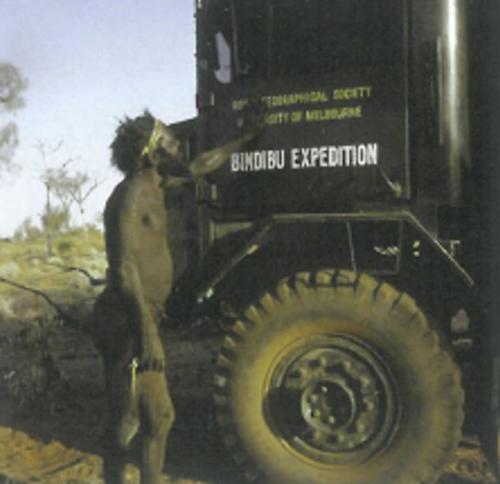

In the mid 20th century, as part of the sad history of displacement that disrupted the lives and culture Indigenous communities all over Australia, the Kaiadilt people were removed from Bentinck Island to the foreign country of Mornington Island. With the outstation movement in the 1980s, partial resettlement of Bentinck Island began, but the Kaiadilt elders have spent half their lives languishing in an alien environment, most recently in an old people's home. Mornington Island has a history of painting, and an art centre, and in 2005 Sally Gabori was taken there on one of the activity excursions often organised by old people's homes everywhere.

She took to painting with a confidence and vigour that would be remarkable in someone of any age, and is almost unimaginable in an elderly lady. The career of Emily Kngwarreye provides a kind of precedent, but she was making batik designs for ten years before she became a painter. A much-admired exhibition of Sally Gabori's paintings was presented at the Woolloongabba Art Gallery last year, and the Bentinck Project now includes the female relatives and friends who have followed her example: her near contemporary May Moodoonuthi, and the slightly younger Ethel Thomas, Paula Paul, Amy and Netta Loogatha and Dawn Naranatjil. The youngest of the group is 67. The influence of Sally Gabori as their leader can be seen in the work of the other painters, and so can the more representational landscape style of Ginger Riley from nearby Borroloola. After only a year, however, the individual style of each artist is emerging. There is a poignant reason why this is an exhibition of paintings by women; almost all of their menfolk are now dead.

To understand how a group of accomplished artists can emerge so abruptly, working in a medium that is totally unfamiliar to them, requires some knowledge of their previous visual art practice. The desert painting that flowered so astonishingly in the early 1970s didn't come out of nowhere, but from the elaborate patterns of ground designs and body painting. The art of the Kaiadilt women, however, is not quite so easily explained. They make shell jewellery and dyed pandanus string dilly bags, and this has possibly contributed to their fine sense of colour. The Kaiadilt also have a tradition of scarification and body painting, but these practices virtually disappeared 60 years ago. Essays in the excellent catalogue of the Bentinck Project exhibition help to explain how this new art movement came about, but the real clue lies in the photographs of the artists at work.

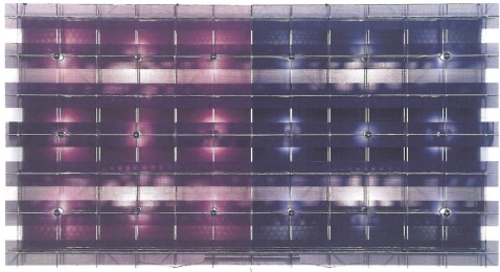

Clearly the Kaiadilt women have, in fact, adapted body ornamentation to painting on canvas, but the obvious connection is not with their jewellery or body marking, but with the clothes they wear. They paint with the kind of colour combinations only seen in the radical street fashions put together from St Vinnies and the kaleidoscopic print dresses sold at Indigenous community stores. In the catalogue photographs, the 1960s polyester pastels and 1970s fluorescent colours of the artists' clothing merge closely with their paintings, just as the ochred bodies of desert dancers merge with the landscape. The art of the Kaiadilt women depicts places on their Bentinck Island homeland, but it has arisen from a synthetic environment.