In her perceptive essay examining the paradox of community, Jill Bennett refers to the post-WW2 era of decolonisation as a complex time of cultural disintegration: at the moment the colonies were liberated from their status as British subjects, some of them sought to return to the 'motherland', thereby muddying the borders that had kept the reality of Empire intact. In the process of creating newly minted nations the notion of a previously exclusive Britishness was subsequently transformed. The creation of a Commonwealth of former British colonies inaugurated a new collective entity, but one forged through contradiction. The Commonwealth was 'a unity precisely in disunity, commemorating the failure to sustain the old colonial identity.' (See catalogue: ed. Charles Green)

The simultaneous dislocation and re-imagining that lies at the heart of the construct of the Commonwealth is the spectre behind the most compelling artists presented in 2006 Contemporary Commonwealth. Twenty two artists – eleven from Australia and eleven from other Commonwealth countries – are installed in the cavernous spaces of ACMI and NGVA, and collectively give voice to the more subtle experiences of identity and homeland that lie beneath the meta-term of the Commonwealth.

For Lorraine Connelly-Northey, a Waradgerie artist from north-western Victoria, the experience of displacement from her land fissured her assumption of indigenous heritage. Reluctant to work with natural fibres – grass and sedge – that would have been used for weaving by her ancestors, she has found a greater resonance in the rusted metal fragments discarded by settler culture; spring mesh from used mattresses or corrugated tin roofing. Self-taught in the methods of Aboriginal weaving yet renouncing traditional materials, Connelly-Northey's handmade objects confound the demarcations of culture: gossamer-like string bags or possum-skin shawls whose rusted form suggest a delicate yet stricken act of cultural reclamation.

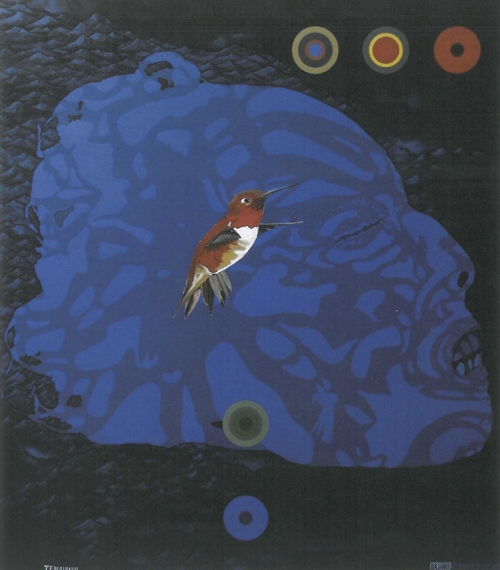

Parallel acts of ancestral excavation take place in New Zealand artist Shane Cotton's large-scale polymer paintings. Luminous blue motifs – native birds, volcanic crests and tattooed heads – emerge from expanses of velvety black. The works explore aspects of Cotton's Maori history, such as the mask carved by his ancestor, Honga Hiki, given to a 19th century missionary in lieu of his own head. The Maori practice of preserving heads (mokomokai) is incorporated: gaunt, petrified specimens reappear in several of the paintings, infusing them with a sense of the uncanny. Small words emblazon the surface. The meaning of these assembled motifs is not explicit, they float in a pool of muted obscurity, genealogies that move in and out of view.

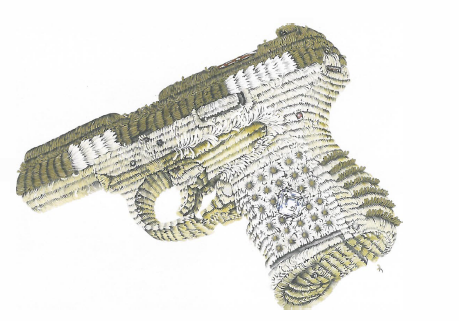

Blatant readings of colonial violence are imaged by artists like Berni Serle and eX de Medici. Serle's 3-minute DVD About to forget pithily communicates the bloodiness of settlement. A red paper cut-out, depicting the silhouettes of huddled figures on hilly land, floats on a body of water. As undulations swirl beneath the water's surface the paper puckers and bleeds, staining the water red. eX de Medici's detailed watercolour drawings feature cartoonish images of skulls and guns, and a decimated forest floor strewn with weapons. In the artist's view, guns are 'the signature of the bully in the world' (cat: ibid).

Two artists stand out for their complex narrative work: Yee I-Lann and Isaac Julien. Both artists interrogate the experience of postcolonialism, uncoiling hybrid histories within the politics of nationalism and race. Julien's Paradise Omeros – a non-linear film that eschews a realist mode – features an adolescent male protagonist traversing the narrative as it cuts between Britain and the Caribbean, English and Creole. Charged sequences with double mise-en-scenes, such as a 1950s working class London apartment depicting a festive party scene in the foreground and a beating in the background, suggest the ambivalence of migration, and its entwined stories of aspiration and subjugation. Footage of race riots is interpolated into the film, and at a certain point the protagonist himself splits into an alter ego, metaphorising the disjunctures within language, identity and home.

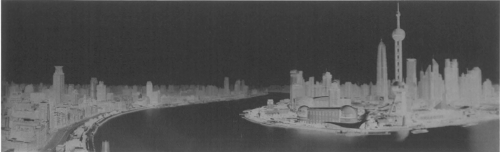

Malaysia as a nascent state on the threshold of political change suffuses the work of Yee I-Lann. Grainy black and white prints in her Horizon Series are shot with an antique camera before being digitally manipulated. Expanses of empty horizon, taken by I-Lann of the Australian desert, are superimposed with symbolic imagery relating to Malaysian identity. Rows of plantation palms, Malaysian dolls clad in national dress, receding blocks of apartment buildings and miniature versions of Kuala Lumpur's Petronas Twin Towers all speckle the horizon. The artist speaks of her experience of being Malaysian as inextricably linked to the 22-year reign of Dr Mahathir Mohamad. A photographed danger sign 'Awas' (beware) is defaced to read 'Wawasan' (vision) – the title of Mahathir's blueprint for Malaysia as a developed nation by 2020. The various symbols are stitched together by the artist, and seem papery and brittle in the face of the engulfing horizon.

The politics of global trade, imperialism and taxonomy are ambitiously explored by Fiona Hall in work that combines conceptual rigour with aesthetic finesse. Leaves of plants harnessed to imperial economies – tea, coca, tomato, ginger – are exquisitely painted onto the surface of banknotes: each leaf and banknote corresponding to a country of origin. The collection encompasses almost 50 nations including India, UK, Vietnam and Spain, and the assembly is lined up in glass cabinets spanning the gallery walls like a botanical panopticon. Adjunct glass cabinets house multiple life-like specimens of birds' nests – each sculpted by the artist out of shredded American dollar bills. The works' considered materiality draws home the inescapable links between capitalism, colonialism and environmental plunder.

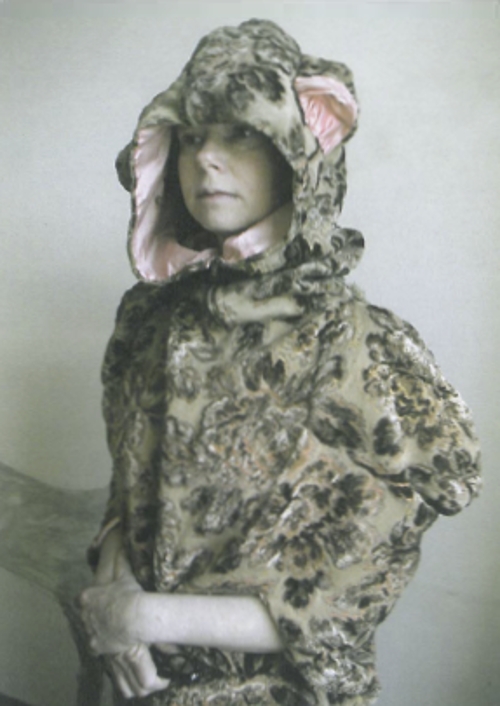

Against the suggestive might of these artists, others seem unsatisfying or thin – such as Rodney Graham from Canada, whose 'costume drama' films make for cloying viewing. Patricia Piccinini's elegant (albeit grotesque) animation When my baby (When my baby) is contextually extraneous, and an obsessive stomach for cold war archival footage is necessary to endure the length of John Hughes' worthy but unwieldy The archive project. As for the inclusion of Jemima Wyman, with her garishly trifling Earthquake Girl, one can only be baffled.

In spite of these discrepancies, 2006 Contemporary Commonwealth is an intriguing snapshot into a number of strains of contemporary art from countries at once meaningfully and arbitrarily united by their status as belonging to the Commonwealth. In contrast to the breast-beating patriotism accompanying the main event – the Games – the artists here represent more attenuated and layered understandings of nationhood.