It has been a roller-coaster ride through three decades for Adelaide's JamFactory Contemporary Craft and Design. Several times it has peaked, only to slip into financial or artistic troughs, but at the moment it is on the upward curve. Under the direction of Stephen Bowers since mid-2004, the inherited financial haemorrhage has been assuaged through tough cost-cutting. His artistic vision, energetic management and credibility as a practising ceramist have helped attract a new generation of young craft and design graduates, including several from overseas.

Symptomatic of the upbeat momentum, the Furniture Studio, which has been closed for two years, is re-opening with a new head, Adelaide furniture maker Tom Mirams. The Gallery, however, has been without a director/curator since the departure of Janice Lally 18 months ago and the Ceramics Studio has a production manager but no studio head. Augmenting his role as Managing Director, Bowers is acting as de facto ceramics head in a reprise of his role in this position in the 1990s.

While the JamFactory's retail operations and gallery program present its public face, a significant percentage of its creative capital resides in the calibre of the practitioners in its four training studios – glass, ceramics, metal and furniture. With a regular turnover of studio heads every 3-4 years and associates (trainees) every two years, the JamFactory experiences perpetual shifts in its artistic identity. The JamFactory Biennial exhibition, which ran through the summer, provided a showcase for the current crop of fourteen dauntingly well-qualified emerging craft practitioners. The Biennial launches their professional practice after years in tertiary training, followed by a two-year stint at the Jam. Overall, the exhibition is an impressive performance from an organisation that has done it tough for the past two years.

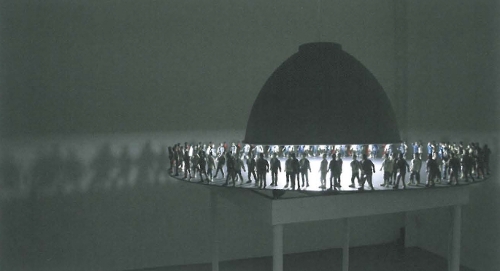

One of the JamFactory's strengths is the range of approaches to craft that it encompasses. This is reflected in the Biennial. One-of-a-kind artworks, limited-run utilitarian vessels and prototype designs envisaged for industrial production sit companionably cheek by jowl. The sublime calm of Deb Jones' abstract cast glass sculpture co-exists with Elizabeth Newman's garish flashing neon triptych on the Madonna/whore theme, and with a dazzling wall installation of glass swords displayed trophy-like over a mantelpiece by Jacqueline Knight. Also on the trophy theme, Metal Studio head Sue Lorraine has created an ironic triptych of laser-cut antler trophies, finished in brilliant red enamel.

Work by Metal Studio associates ranges across the spectrum from streamlined prototype cutlery by US designer, David Zitnik, fabulously inventive insect lights by Carmen Liang, well-crafted approaches to wearable jewellery by Sally Mahoney and Shauna Swanson and disposable body ornamentation using adhesive paper shapes by Tassia Joannides. The Ceramics studio is equally diverse with decorative ceramic cricket bats from English associate Isabella Niven, Jane Robertson's suite of simple vessels distinguished by a delicate speckled clay body, and celadon-glazed ware from Charmaine Hearder and studio manager Phil Hart.

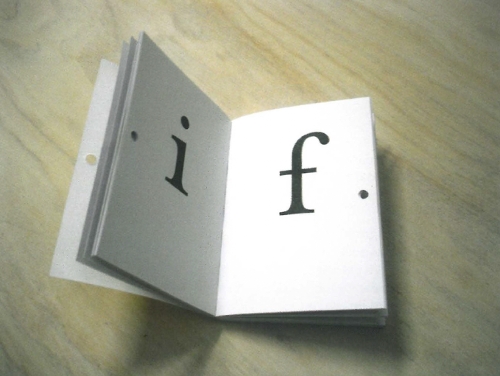

The Biennial affirms craft as an inclusive term embracing a diversity of practices. This stands in contrast to the flyleaf of Kevin Murray's recently published book, Craft Unbound, where he asserts that 'The history of craft is a battle. The exclusivity of refined taste is pitted against the camaraderie of honest work.' Murray is right about camaraderie. Regardless of its financial travails, the Jam has always generated around the clock palpable energy from hard work and communal effort. Slow, dirty, sweaty, skilled labour (nourished by a deep-seated love of making) are behind the aesthetically complex, meticulously crafted work that ends up on pedestals in a gallery environment, appealing to refined tastes of both the viewing public and the collectors. The two are not in battle but indissolubly linked.

Murray's pumped-up blurb tries overly hard for controversy at the expense of truth. It may work for selling books but it is an ideological distortion of the inclusive nature of the continuum of contemporary craft and design practice. Refined taste is not the enemy of skilled work. Nor is there one type of craft that is inherently more 'honest' than another by virtue of ideological slant. It is possible to admire Deb Jones' subtle glass sculpture, the clever irony of Sue Lorraine's Dear oh Deer antlers and the humble beauty of Jane Robertson's utilitarian stoneware vessels without undue inner conflict. At a time when craft is being squeezed into a shrinking gap between art and design, when the word has been symbolically deleted from the re-branded Visual Arts Board, let's not turn it into a hypothetical battlefield and create false dichotomies.