As a graduated Australian Museum curator (2001) and Dept of Social Security death clerk (1984) I've had my fair share of the surreal and macabre. Indeed, as the clientele of both dropped like flies neither organisation managed a sense of purpose - let alone irony and style. Not so, at the moment, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

With swallowswenson, an exhibition of sculptural works by Ricky Swallow and Erick Swenson, the MCA again proves that substance triumphs over Monet, and free entry guarantees numbers every time. Though the less said about the elephants the better.

Not withstanding the odd dissenting trill, the brilliance of Ricky Swallow is apparent. An impetuous virtuoso and deft technician Swallow rightly garners critical and audience acclaim (and big prices). But the standout of swallowswenson is not the overtly lauded Swallow, but co-exhibitor Erick Swenson. The Texan's Australian debut is a corker.

The temptation to compare and contrast the two is irresistible. Much is made of the artists' similarities: whimsy, purity, pathos, theatricality and technical ability. All true. But, it's their difference of depth that's illustrative.

On reflection Swallow's meticulous nostalgia seems slightly juvenile when viewed against Swenson's mature and lyric pitch. Similarly so when stacked against the sub-currents of bleak tumult and sensual cynicism contained in Swenson's work. While Swallow yearns for yesterday's BMX Swenson revels in divine metaphor and emotional firestorm. Enough said.

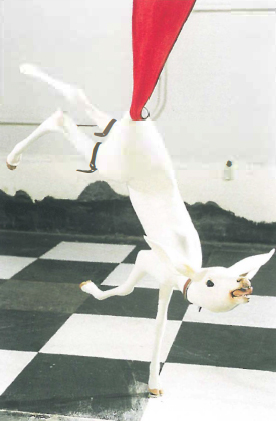

All felicity and menace Swenson's Untitled, 2000 presents a bleating fawn spiralling skyward caught within the folds of a sinister cloak. Erotic and histrionic the work is unsettling in its violent lust and panic. Its charge and resonance lie in the artist's ability to suggest a myriad of narratives and interpretation. Whose is the macabre cloak? A mad prelate? A cheesy magician? Dracula?

This unheard fawn, so beautifully rendered in fibreglass, flocking and plastic, is perfection and temptation. Yet, why are its sexless and succulent flanks and neck collared? This haunting S&M scenario is no mere reference to Dorothy's Toto. Never glib, this work owes more to G. L. Bernini than L. Frank Baum.

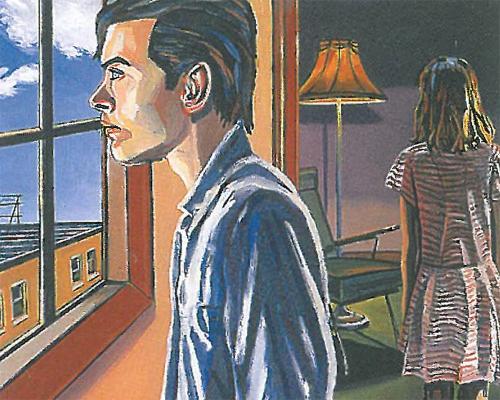

Across the room the newly crafted Untitled, 2001 skips through similar territory. Casting a saucy glance across naughty shoulders another fawn invites ecstatic fantasy. What's her story? Whether coerced or willing she impudently offers her buttocks whilst provocatively rubbing (and shedding) her horns on a computer generated carpet. Again, the metaphor is more baroque than Broadway. As with Canova's 'Pauline Bonaparte', the temptation to touch is almost irresistible.

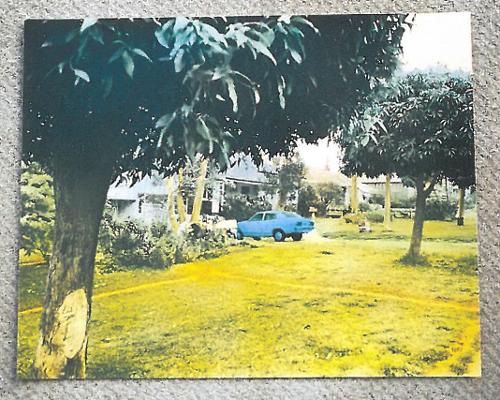

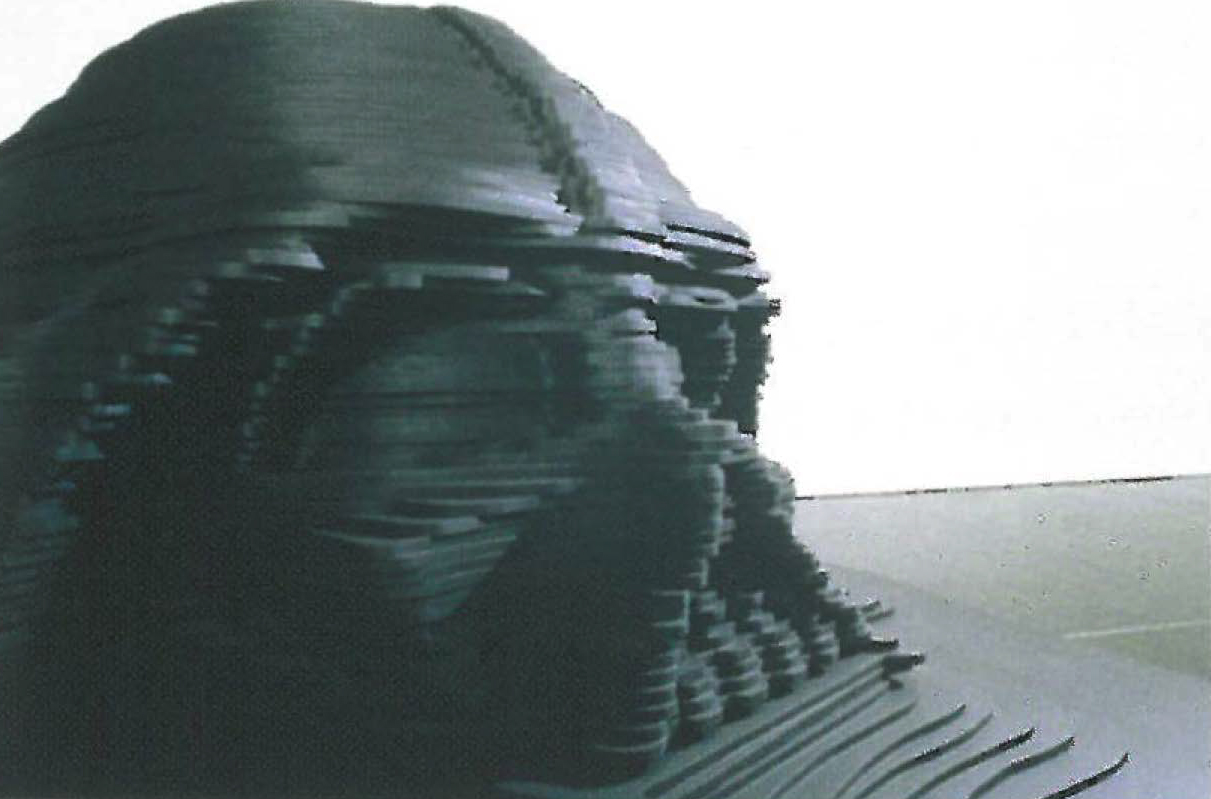

Swenson's final work Edgar, 1998 is equally fanciful and bravura - a Myer's Christmas window on angel dust. But this is more than demented window dressing. Fright-eyed and solitary Edgar, an apocalyptic mongrel if ever there was, stands frozen and forlorn. He sears our hearts and warms our eyes. So gorgeous and bathetic is Edgar that you simply don't know whether to laugh, cry or both. His fate? Probably an icy knackery.

Overall, the only quibble is that Swenson, so brilliantly cinematic, does not (as in other exhibitions) transform and transcend the gallery space. Obviously, at the MCA this movie has no set. Pity.

Once witnessed in the crypt of the Vatican was an act of extreme piety. Arse up and sobbing, a plump matron hoisted her skirt, ducked a faux velvet rope and threw herself on a slab (Pope John XX111). It was a biblical moment. For most at the MCA Erick Swenson cuts the rug in much the same way.