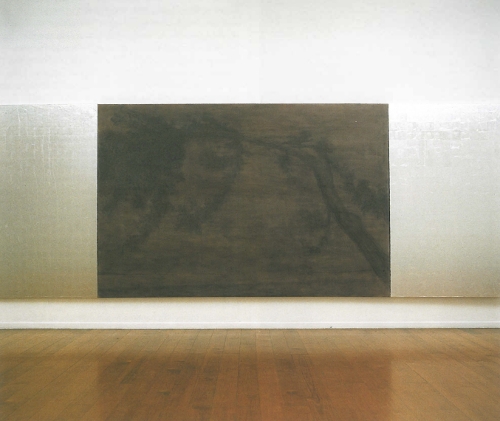

Three granite boulders impregnated with electronic dials and heating rods rest on individual timber platforms. The potential for mobility, to be rolled, pulled and lifted, is in abeyance, the elements instead tied clumsily to the wall with gaffer taped extension cords and adaptors. Imagined hum? It takes a moment to break the habits of a well-behaved art viewer and risk physical contact (the laying on of hands) and confirm the heat emanating from within. Hot rocks. It is granite after all, naturally radioactive.

The work's title, Mount Hopeless, evokes the magic of proper nouns that mark out trajectories of travel and imagination. The name sends me elsewhere on my own journey of geographical name contemplation, in pursuit particularly of those names that trace colonial expansion – the expeditions, in Australia and elsewhere, that sought to both know and claim the natural world for scientific and economic ends. Consider, for example, the remarkable number of Mount Pleasants in the world which, together with Prosperous, Plenty, Abundance, Desire and Hope, speak of naming itself as an act of wishful thinking and wilful intent. Names more telling of the vagaries of nature and lived experience include Mount Horrible, Fatigue, Dispute, Deception and Misery. One of the two (at least) Mount Hopelesses in the world is situated in South Australia at the northern end of the Flinders Range. Named by Eyre in 1840 during an attempt to open up a route into Central Australia, Mount Hopeless marks the extent of Eyre's northward journey and the point at which he surveyed the surrounding land and decided upon its incapacity to allow passage or support stock. This particular Mount Hopeless is also cited as a physical landmark in tales of Sturt's 1844 expedition into the centre, and in the tragic tale of Wills and Burke in 1861 – who, having missed help at Coopers Creek by a single day, set off towards Mount Hopeless in search of aid. Hardly propitious.

So perhaps hot rocks hint at more unpleasant ends than just the heat on one's skin, resting in the sun against a boulder. Heat, after all, is more than a temperature to be manipulated between two ends of a dial (as knowing where you are won't necessarily save you – especially when lacking other kinds of cultural knowledges about the land).

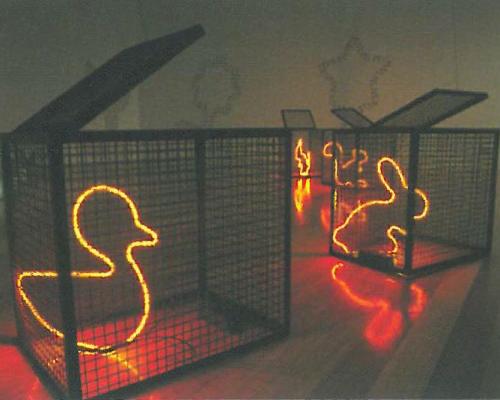

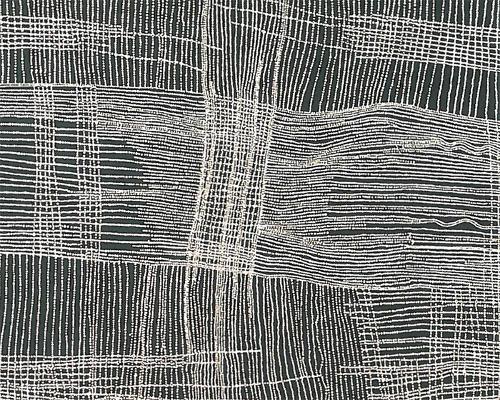

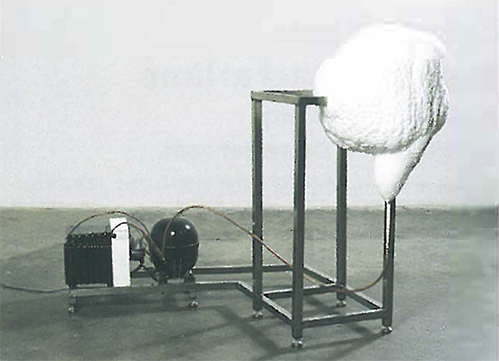

In combination, the four artworks in this solo exhibition hark back to earlier quests to know the natural world through scientific endeavour and physical exploration of landscape. Traces of the romantic sublime hover round Solidified Spirit, a mass of quietly active ice cohering round a stainless steel frame. Televisual snow, a blizzard of white noise, is made available for contemplation in Have Decided It Shall Be Natural. Contained within an aluminium travelling trunk, a hissing speaker relays the sounds of the ether (evidence of an exterior world of order and chaos). Speculative Knowledge, wall mounted electrical fans, circulates air like thoughts.

Nicholas Folland's works appear as experiments reflecting upon process and the construction of knowledge. They evoke studies of earth and air, wet and dry, hot and cold; they play with mobility (placed and placeless), containment, and the imaginative quest to encompass the elements of 'nature' and 'landscape' – while pointing to the ambiguities of their own task, to incommensurability and unpredictability, the pleasure and risk of knowing and perception.