I am wary of approaching anything marked "installation". Rather than leaving the viewer to casually saunter around the gallery gazing at individual art works neatly categorised under a title or specific theme, installation swallows you whole. In order to visually penetrate the work, one must become physically immersed in the artist's domain. I often feel as though I am trespassing onto sacred ground or secretly peeking into the cloistered recess of an intimately embellished cubby house. From this point, it is harder to remain aloof and unattached. Installation is contagious: it crawls over the walls and leaks into the floor. Installation does not hang quietly. It invades.

Invasion was the operative word for Matt Calvert's recent installation, Too Strange. Using discarded materials found in the subways of Sapporo, Japan and glass (broken and intact) scrounged from various sources in and around Hobart, Calvert produced a series of works that, when placed together in the gallery, both attracted and repulsed.

Similar to the windy, narrow cavern of an underground railway system and the claustrophobic corridor of a sweaty rabbit warren, the entrance to Too Strange was via a series of twists and turns through a dark hallway. Moving hesitantly out onto the vast polished floor of the gallery I was greeted by an open vista of sentimental shapes.

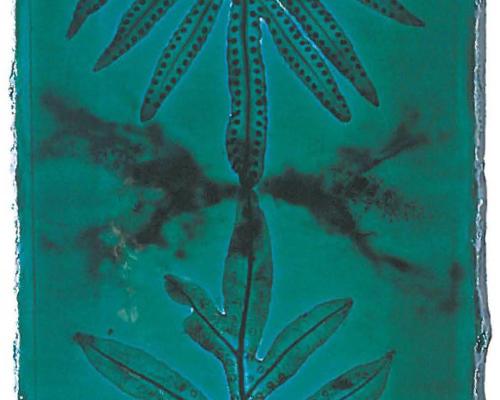

Pudgy blue and red bunnies, mice, ducks and squirrels clustered in a circle on the floor while a group of their larger than life siblings sat flat on the wall showing off plasticy grey fur made from rail cards. Ample outlines of tulips and roses grew from the floor onto the opposite wall and created an idyllic space filled with all things cute and homogeneous. As I looked around, the opening melody of Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun blew like a warm breeze through my mind. Was this paradise?

Drawn closer by the alluring sweetness of the delicious bunnies, I soon realised these stout little figures were not as amicable as they had first appeared. Their smooth surface now revealed thin veiny cracks and gave way to a body made up of splintery shattered glass the colour and texture of a Blue Heaven slush puppy. Crouched in motionless vigil, the fragile glassy foes stared blindly at a similar collection of animals trapped in several black wire cages. Moulded from anxious red neon, the caged animals hummed and crackled with electricity; their bodies emitting a sinister heat. Cowering in the corners of the cages, the animals seemed ready to pounce from their pens with a crazed burst of volcanically hot voltage. In the distant background broad bending blooms goofily drooped their sleepy oversized heads and surveyed the scene with quiet anticipation as the air hung thick with mute squeaks of escape.

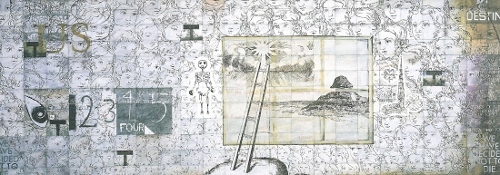

Breeding over the walls the contours of animal and flower held the encoded labyrinth of a thousand journeys within their railcard flesh and spoke of a kind of fluid movement the icy bunnies and red hot squirrels would never know. Adorning the front of the cards were the smiling faces of cartoonish elves, Santa Claus, roly-poly teddy bears and jolly men in business suits. Like the eerie ashen shadows of a child's mobile when the lights go out, the shapes on the walls loomed in a garish fantasy of overbearing cuteness and the cool simplicity of Japanese urban aesthetic.

Reminding me of the saccharine sculptures of Jeff Koons, the nostalgic childhood toy monuments recreated by Michael Doolan and Emily Floyd's recent exhibition of chalk drawing rabbits, Calvert's pretty petrified creatures shivered and singed their way through a post modern playground of mutated fauna and cleverly positioned traps. Lovingly caress the squirrel's tail and she will burst into a thousand piercing pieces or dare to place a hand inside a cage to beckon a mouse and risk being burnt. Calvert's objects entice one to play, yet at what cost? In an increasingly mechanised world with super cities like Tokyo and Osaka rapidly accelerating into the metallic realm of technological giants, is it safe to play anymore? Cast out of Calvert's modern Garden of Eden scratched and scarred, we turn back to the scorching light of reality and find our way home. Back to the devoted charms of a cherry blossom iMac, chubby little Volkswagen, the sweet tinkle of a mobile phone and the excited salutations of a robotic Aibo puppy. Let's hope he doesn't bite.