Joining the many publications about Indigenous art and artists published in the last ten years is a slim, handsome softcover called Kathleen Petyarre. Genius of Place. It's second in a series initiated by SALA "showcasing the work of South Australian living artists".

The book has a number of colour plates of Petyane's works with essays by Christine Nicholls and Ian North, both Adelaide-based academics.

Kathleen Petyarre shot to national prominence in 1996 when she was the recipient of two national Indigenous art awards in one year: joint Second Prize in the Australian Heritage Commission's NATSl[1] Heritage Art Award; and the 13th NATSI Art Award for the painting Storm in Atnangkere Country II.

So, do Petyarres's achievements and body of work make her a 'great artist' or even Genius as the title implies? This is the question the authors of the two essays appear to be endeavouring to address.

The essays are significantly different. Christine Nicholls has been a long time friend and associate of Petyarre's although in her primarily biographical essay about Petyarre we are not given any insight or background to the relationship between the women. This is to the detriment of our understanding of the essayist's role in the career of the artist, which has been significant.

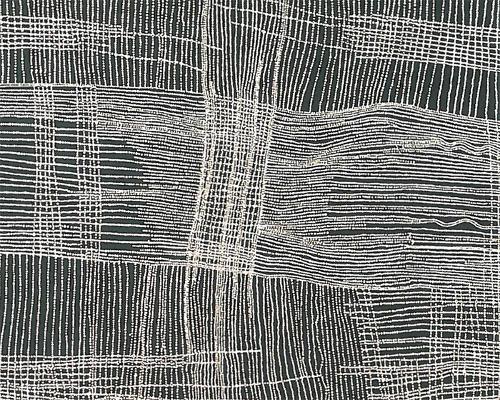

Nicholl's essay reads beautifully and yields up fascinating information about the artist and her life experiences, motivations, and aspirations. Petyarre is an Eastern Anmatyerr woman whose country is Atnangker (north east of Alice Springs) in the Northern Territory. English is not her first language. We discover that Petyarre was a teacher's aide in the small Utopia School for twenty years. She was active in the batik movement which started in 1977 and took up painting in the early 1980s - although apparently her early works were not especially promising. Nicholls' writing is strongest when telling us about these early years and describing custodial relationships to land and Arnkerrth (the quirky 'Mountain' or Thorny Devil) the 'Dreaming narrative' or creator being over which Petyarre has custodial rights and which is the subject of so many of her art works. From an early age she wanted to know more about whitfellas, welcomed opportunities to interact with them and expressed the desire to be a famous artist. Her relationship with Gallerie Australis since 1992/93 has been an integral step in her fulfilling that aim.

The essay inevitably addresses the notorious 'authorship' controversy and here it is least satisfying for me. We are told that from 1991 to 1997 Petyarre had a de facto relationship with a non-Indigenous man, Ray Beamish, who collaborated (claimed to have "painted the lion's share") on some of her most celebrated paintings. At times they lived at Utopia and others at his mother's home in Adelaide. His revelations in late 1997 caused a furore and for a period of time cast a cloud over her winning the NATSI Art Award in her own right. His claims aggrieved Petyarre and the resultant debate created tensions throughout the Aboriginal Arts industry. No doubt many contributors to the debate had minimal, if any, knowledge of traditional cultural practices.

The incident was of great interest to many of us who have worked directly with Indigenous artists and been faced with the issue of provenance, of attribution of 'authorship' on a daily basis. Nobody denies that collaborations take place, but what to do? In an art centre one is always being called upon to establish who has participated in the act of creating an art work and who should be attributed. With the market demand for work by the master artists there is money to be made or lost depending upon attribution. In some centres it is common practice to identify all painters, whereas for years the women relatives of Papunya Tula artists laboured on men's canvases anonymously. Yet the skill and touch brought to an art work by the support painters can significantly influence the aesthetics (and resolution or success) of the finished painting.

It is here the author lapses into subjectivity. Rather than debate and enlighten the reader about the issue of 'ownership/custodianship' of 'Dreaming' stories and how this has been translated to 'authorship' as it relates to specific art works, she instead belittles Beamish by making character judgements. "Kathleen Petyarre is an erudite, familyoriented Anmatyerr woman, deeply immersed in Anmatyerr Law and in her Dreaming, and a pillar of her community. Ray Beamish is a dreamer and drifter with a passion for big motorbikes." Well, we can't trust him then!

It was a shame that the authorship debate was, at the time, so vitriolic (and you were either for the individual players or agin them) that there was no room for constructive discussion about a genuine dilemma that confronts arts workers regularly. In fact it arose for me again last week in an art centre in Arnhem Land, but this time in relation to an ageing famous artist and his wives. Of course in the Petyarre instance the issue was complicated by the race of the collaborators, all the more need for decent debate. Nicholls states: "In Anmatyerr law, dots are the least significant aspect of the painting, often, though not always, thought of simply as infill." But this begs the question, what are we to make of paintings that are nearly all dots?

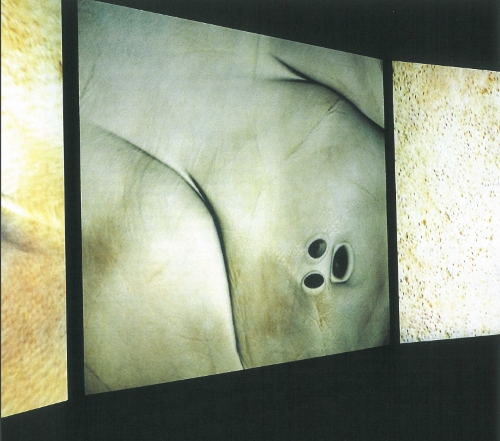

North's essay begins on a personal note with him detailing his observations of his first visit to Kathleen's home in the desert. It is full of raw culture shock, his sense of dislocation, discomfort, heat and attempts to make sense of the situation. He ponders whether warnings issued by Petyarrre about drunks are justified or an expression of Petyarre's 'kindness', the title of his essay and one of its themes. But then we are suddenly back in North's more comfortable home turf; art theory and grappling with the big questions such as the idea of "the aesthetic working cross-culturally", taking detours into recent evolutionary and psychoanalytic theory to help us make sense of it all. Whilst at times North makes accessible (to me) points about Petyarre's art making and its place in the world I found much of the essay very heavy going. It left me pondering the interface between my obtuseness and the opacity of some academic writing.

So, is Kathleen Petyarre a great artist? The judges of art prizes must have found her paintings gobsmacking in the flesh. The colour plates are good reproductions but being works of immense subtlety they lack power when reduced on the page. Seeing them as a group also raises the issue of repetition of representation. For example, juxtaposing the Sandhill Country paintings (1999), with and without hailstorm, on alternate pages illustrates my point and there are other examples.

The cover notes state: "this book is essential reading for those who wish to move beyond superficial understandings of contemporary Indigenous Australian art". Certainly it presents much food for thought and two very different perspectives on the life and work of Kathleen Petyarre. What are we to make of an artist who, in her own words, "tried really hard to do the painting the way whitefellas like it"?

Nicholls states: "It says a good deal about Kathleen Petyarre's highly developed crosscultural facility and skills that she was able to gauge with such accuracy the mood and desires of the mostly metropolitan-based art markets". Indeed it does.

Footnotes

- ^ National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander