.jpg)

Jeffery Smart belongs to that most select group of artists: they who were born between the two world wars, who matured as artists in this country, and went on to achieve substantial success on the international scene. As such, Smart looks and plays the part of the elder art expatriate well. Urbane, impeccably groomed, and somewhat acidic in his views of the contemporary scene, Smart regularly returns to these shores to due acclaim, press notices and sales. The Heide Museum of Modern Art was the venue for a spectacularly successful retrospective of his work last year, and in September of this year some of his more recent paintings were on show in Brisbane. Australian Galleries had a concurrent exhibition of drawings in Sydney, which also had a showing in Melbourne.

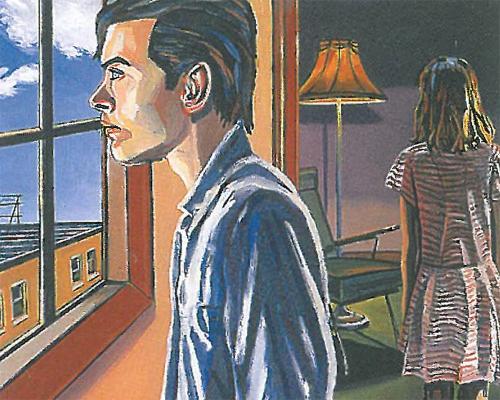

Few painters are as meticulous in their preparation for a major canvas as Smart. A lifelong devotee of Piero della Francesca and the early Italian Renaissance, Smart takes the working method of such masters as his own. In all but his earliest works, Smart's paintings proceed through a series of drafts, directly comparable to those of a writer, starting with drawings to establish detail, but especially to formulate the composition itself. As with the productions of an author, what matters is the final draft, the rest being the means to an end. This does not mean the drawings lack merit as artworks in their own right - far from it - but their main interest is in providing evidence and clues to the artist's progression of thought, the countless decisions involved with the evolution of a picture.

All of the work upon which Smart has built his oeuvre falls within the realist tradition. This is not a matter, however, of the artist simply recording the physical world. Each major piece - that is, each final, definitive painting - is a machine, a device to explore painting's abstract qualities. Above all else, Smart has explored and extended the Quattrocento's project of composition, the development of a formal visual language exploiting colour, tone and above all, the wonder of that age: perspective.

.jpg)

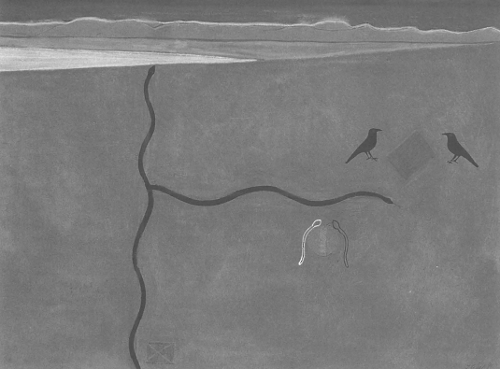

The Australian Galleries shows were quite comprehensive, with over two hundred works ranging over nearly sixty years. There are no grand gestures in these drawings, save one: a study dating from the fifties for Temptation in the desert, combining loose penwork, strong colour and the dramatic pose of the figure with its outstretched, upraised hand. This was the lone histrionic note in the exhibition, but by no means the only theatrical one. Many of the compositional studies - as with the paintings they prefigure - have the quality of stage settings. It is as if the figures - indeed, the streetscapes themselves - are waiting for the action to begin, a drama to unfold. Again and again in his paintings Smart suggests time itself through his use of light, which is raked over his urban settings, set off against dark skies.

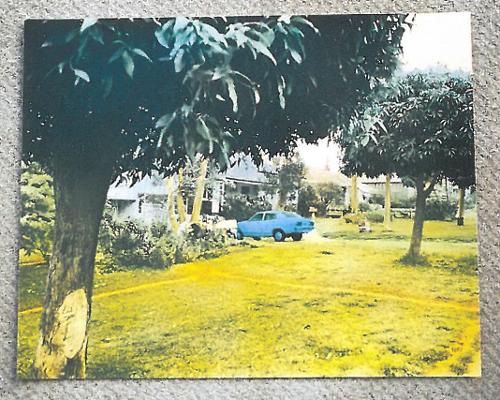

This motif and its associated elements appears in these drawings for the first time as early as 1951, in War memorial, Adelaide. This small, loosely sketched ink and wash work has a completeness that distinguishes it from the bulk of the studies. Trees and war monuments tower over a handful of schematic figures. The sky is picked out in black ink. The monuments themselves, a soldier with raised gun and a first world war artillery piece on its carriage, are at least twice oversize and dwarf the people. An air of disquiet hovers over the scene.

Throughout his career however, Smart has rejected readings of his works as images of alienation. Certainly there is little amongst the drawings and studies to support this reading. A number of ink and watercolour works of the early fifties depict tired or decrepit urban settings, but they appear to have more in common with an aesthetic current at that period, at once gritty and romantic, exemplified by the Hill End artists. It is in much later drawings where Smart finds subjects worthy of his most attractive treatments, in studies of wheels and tyres, in details of roadworks furniture, in concrete ramps and railway platforms.

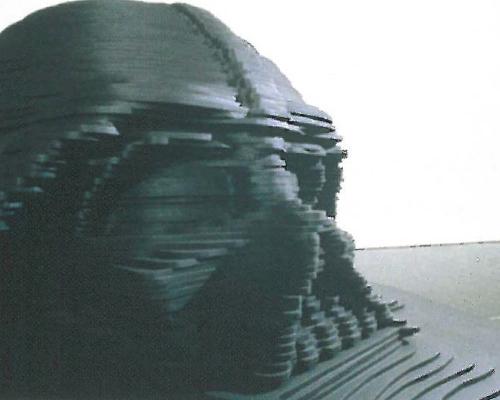

Retrospective shows allow us to see the drift and change in an artist's style. The earlier, more modulated approach to mark-making is replaced in later years by a somewhat impersonal technique, a good example being The Sardinian's house, a 'finished' ink and watercolour of 1995. As drawings per se they may be a little dry for some, but for the insight that they provide to the artist's processes of creation, and the central place of drawing for this particular painter, this was a rewarding show.

.jpg)