What is the fate of women's domestic arts? You won't find it in art galleries or art education syllabi and rarely in critical analyses of art and craft. Beyond agricultural shows, hospital auxiliary kiosks and homes of the elderly, it usually ends up tossed out or salvaged by op shops. Handicraft, hobby craft, or in the words of an artist friend "auntie craft" - call it what you will - the gentle arts of crochet, knitting, cake decorating and similar pursuits have virtually no place in the art community, despite three decades of feminism and two of postmodernism.

This inability to speak about home crafts and hobbies within the hallowed sphere of art has, nevertheless, been challenged by a jointly curated exhibition by Vivonne Thwaites and the South Australian Country Women's Association. Home is where the heart is examines overlaps between the art of twelve Australian women artists and their less acknowledged, sometimes anonymous but highly skilled progenitors.

In a provocative and richly researched essay, Mary Eagle asserts that it's not the art world but the CWA which "represents relatively free territory" for creative expression. This national organisation boasts a history of community social activism and inclusivity, where cultural differences of indigenous and migrant women have long been embraced, supported and promoted. Together with Stephanie Radok's lyrical reflection on homeliness, the traditional CWA image of housewifery for idle hands is expanded beyond starchy matrons, fluffy scones, matine jackets and docile stitchery - not to mention those giant aluminium teapots on the go at fates, funerals and other functions - to encompass a bold political and creative dimension.

'The gentle (or lesser) arts' have been advocated and taught by CWA groups to thousands of Australian women since 1929, emphasizing the virtues of skill, creativity and self-fulfilment and works by SACWA members, together with fascinating documentation, are included in a smaller, separate chamber of the Art Museum. To some extent this placement suggests a genteel historical context for, rather than a partnership with the 'real art' in the main gallery.

Contemporary artists have responded to this heritage with varying degrees of acknowledgment and potency. Aadje Bruce nestles a child's handknit against a larger pullover front, still on the needles - not yet 'cast off', yet forever abandoned. Both are poignantly dotted with downy feathers and redolent with generational narratives.

Memories of home dressmaking, with its prickly pins and crinkly paper infuse Helen Fuller's Wallflower dress patterns. Made of greasy lunchwrap, wire and brown paper, they are hung upside down, stiff and gaping, and powerfully evocative of 1950s virginity. Eschewing this scratchy but affectionate response, Michelle Nikou's lumpy lead teaspoons suggest a sinister underbelly to domestic life. Elsewhere, she gently camouflages a couple of conceptual coat-hangers amongst a diverse collection of their pre-loved cousins.

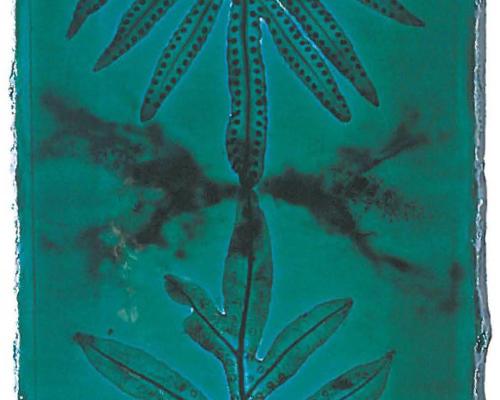

Natural materials crafted into figurative forms draw upon indigenous traditions long associated with CWA classes. Guildford grass creates Storyteller and a wistful Chinaman for Nyoongah/Noongar artist Joyce Winsley, while Yvonne Koolmatrie fashions rushes, sedge grass and echidna quills into Ngarrindjeri river creatures, Echidna and Turtle. Of all the artists' works, these seem closest to the heart of the CWA ethos of inventiveness and making do. Similarly, a wonderfully impossible chicken wire jug by Jo Crawford suggests the surreal slog of rural hardship, as does Irene Briant's Another Sky, a rusty iron Rheem plate, edged with knitted lace border - in gold leaf pattern.

Despite the pull of Nalda Searles' Xanthorrhoea blanket book, Kay Lawrence's pristinely rusted tapestry, Sarah Crowest's patchwork fragments, Julie Gough's political retro-basketry and a mellifluous rag rug by Rosemary Whitehead, I found myself returning to the domesticated CWA space - out the back - to become riveted by two aprons from Hermannsburg Mission. Brightly coloured and neatly pressed, they were embroidered with pattern-book boomerangs and cliched 'nativist' motifs, but were haunting in their cross-cultural and, as artist and apron scholar Avis Smith suggests, their "frustrating" anonymity. Ironically, these garments perversely summoned up the spirit of Margaret Preston's 1925 dictum that indigenous design could usefully be applied to modernist Australian art.

Preston also reminded us that the beginning (of art) should come from the home and from domestic arts, but three quarters of a century on this continuum is yet to be acknowledged. Until now art world orthodoxy has proved too stitched up to honour its origins, nurtured as they are within the realm of women and home.

Even in this exhibition 'parity' might have been better achieved by a more integrated hang and perhaps anonymous or collective labelling throughout, rather than consigning much CWA work to obscurity, in Smith's words, as "forlorn little pieces of women's craft, spilling out of (Op shop) drawers" As what Jennifer Craik calls the "research and development component of professional art" it is worthy of more dignified presentation. Nevertheless, Home is where the heart is has begun a significant aspect of research, and more importantly, has initiated some creative unravelling between the separate worlds of art and the heart.