In the seventies, it is widely believed, Western art lost faith in its own originality and got caught in an endless retro-vision. There was nevertheless something terribly original about the art they produced.

These thoughts went through my head when Domenico de Clario showed me the premise of an exhibition he was curating called For Nothing. It read like a manifesto from the seventies:

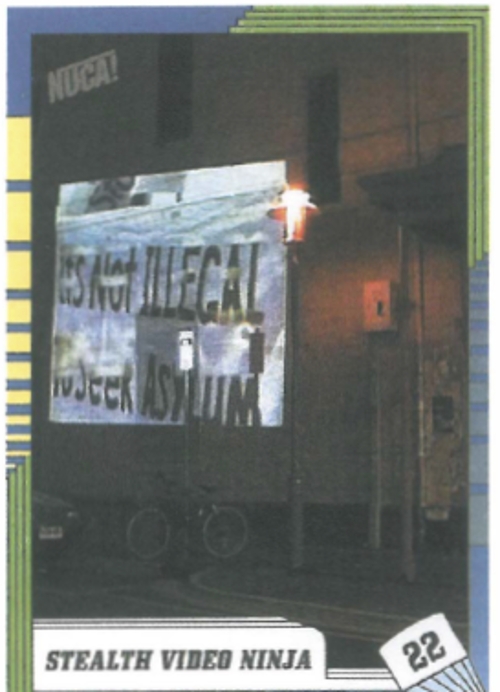

Is it possible to make a work whose raison d'etre is not dependent on critiquing another artist? Is it possible to make a work that does not cost anything to make, that does not aspire to be sold and that does not refer to anything other than itself? Is it possible to make a work whose values run counter to the society we live in? Is it possible to make a work that does not consider itself as art?

So what happened in the seventies? Unable to say what art was in any positive sense, artists outlined what it was not. Like negative theology (the god who is beyond god) art now lay somewhere beyond art. In a flight of idealism, art became post-object; and through this intangibility, through these nuggets of Platonic truth, artists hoped for redemption. In the parlance of its own time, it inhabited the interminable repetitions of Derrida's differance. This essentially mystical notion of art rejected the positivism of our age and reminded us of the nothingness that is the beginning and end of all things.

The seventies have assumed a mythic presence in contemporary art, even if its gods still live amongst us. Two of the most heroic are Stelarc and Mike Parr. Perhaps they stand out because the violence of their art spoke most forcefully of the endgame being played out. Others, such as de Clario, sought a certain innocence, truth in silence and seduction rather than shock.

Marx said that tragedy repeats itself as farce; but how does innocence repeat itself without losing all credibility? Quite easily really, for what de Clario sought was a poetic state of becoming that, through accepting the small tragedies and chance beauties of everyday life, constantly renews itself. It is a practice that grows in strength and understanding through its very repetitions, for in essence it is a form of listening rather than declaration, and since moving to Perth several years ago de Clario has continued his quiet ways in performance and exhibitions.

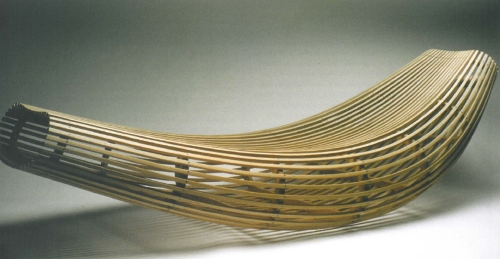

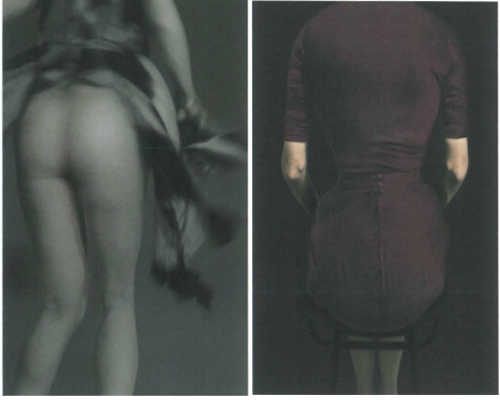

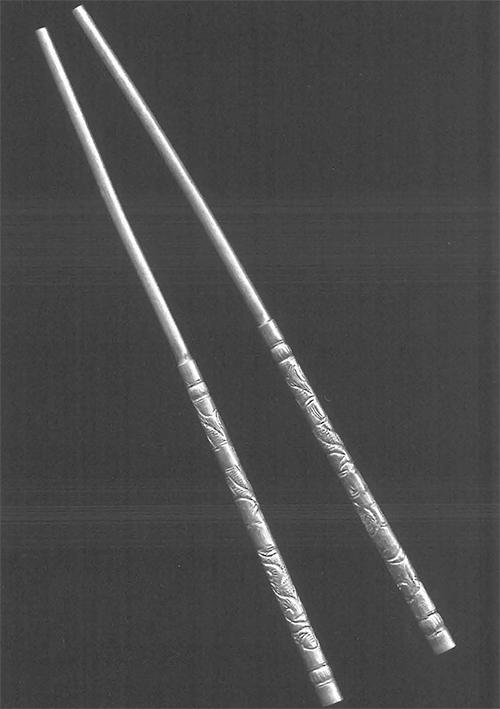

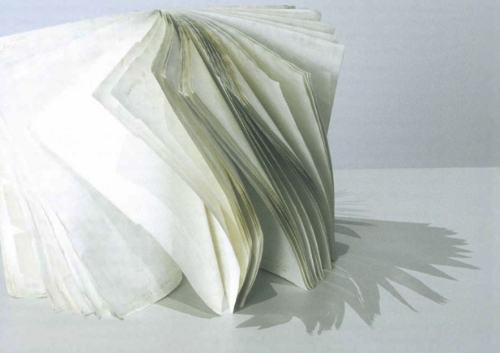

For Nothing includes an eclectic array of work by 17 diverse artists from every continent, with about a third being local. Some art comes alive in certain exhibitions, as if the exhibition was its destiny. This is not the case here. Indeed, each work could be a door to another exhibition. However de Clario has chosen his artists well, for the works also form a loose improvised medley, much like a de Clario piano recital or installation – as if there is a second invisible exhibition with the curator as artist. There are very beautiful moments, such as Elizabeth's Presa's floor piece made from hair, a summer dress and a puddle of milk, or Sumi's egg also made from hair. There are even objects that look like art, such as Tony Nathan's large digital photographs of abandoned 1970s architecture set in the washed out tones of the urban periphery. There is a music score (Liza Lim), and also an ironic narrative about the limits of art (Noel Sheridan). And, as we have come to expect with de Clario, there is also the detritus of everyday life.

What links these works is a series of negative questions circling around the underlying unanswered question that has motivated art since the 1970s: what are the values that contemporary art upholds? There is, says de Clario in his catalogue essay, 'no clear answer'. But these works do offer a way, a sort of Buddhist sensibility that finds in the acceptance of the banal and everyday an ethics, as if the pot of gold at the end of rainbow is in small things, in ruins and flux. If in the modern period theology disappeared into aesthetics, today aesthetics is disappearing into ethics, that is, back into, theology.