This survey of Vivienne Westwood's fashion, originally held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, has been heavily promoted as presenting her as the ironic queen of fashion. Sadly the exhibition treats its subject with such reverence it is as though Westwood has been given an irony bypass. The problem starts with the display. Despite the sheer exuberance of Westwood's signature style, the exhibition is shadowed in so much gloom that the lighting consultants could work for Bill Henson.

The most puzzling curatorial decision in the display is to separate the work into two phases: Punk and the rest. This comes with an unstated implication that Punk is the foundation of Westwood's oeuvre, but that she has moved on so far that it needs to be isolated, kept on as a prelude to the later greatness in tweeds and crinolines. It is in short a minor version of the Routinization of Charisma, Weber's theory as to how revolutionaries are scooped up and absorbed into the establishment. Westwood could be the poster girl for this notion as with McLaren and a shop called SEX and the 'World's End', she created the upmarket look of English rebellion.

This interpretation is reinforced by Claire Wilcox's hagiographic catalogue with its absurd claim that Westwood and McLaren 'launched Punk'. Punk came from the same energetic sources as Pop art and Liverpool beat – the post WWII cultural dislocation when the certainties of class were damaged in the Blitz and there was a window of opportunity for new ideas. This is the context for the emergence of the Situationists and related ideologies. This was the society that produced the sartorial extravagances of Teddyboys and Teddygirls, Pop art, Merseybeat, and Punk. Douglas Adams wrote of destruction and a restaurant at the end of the universe in A Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, a nihilistic concept that was later worked over in Westwood's World's End shop, with its clock going ever backwards in a thirteen hour day.

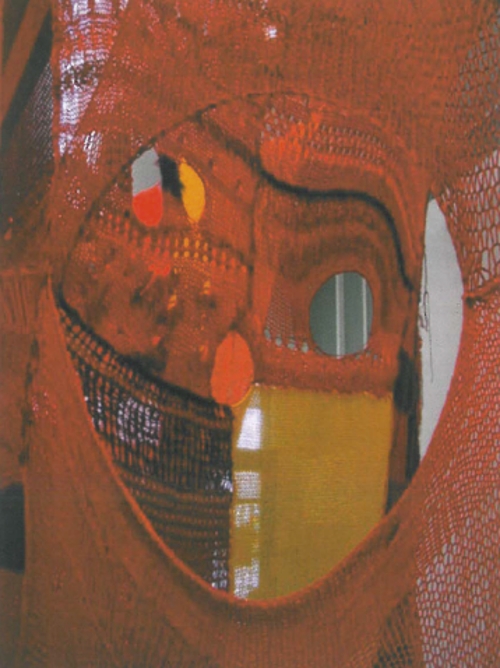

Given this context Vivienne Westwood has to be seen as an extreme appropriator. Her clothes of this period are truly amazing; mixing vernacular art school grunge and s&m latex with such panache that fashion was never the same again. The styles that she exaggerates and manipulates, parodies and adores, show a certain consistent and narrow sensibility, one reason why she was so heartily embraced by the English establishment.

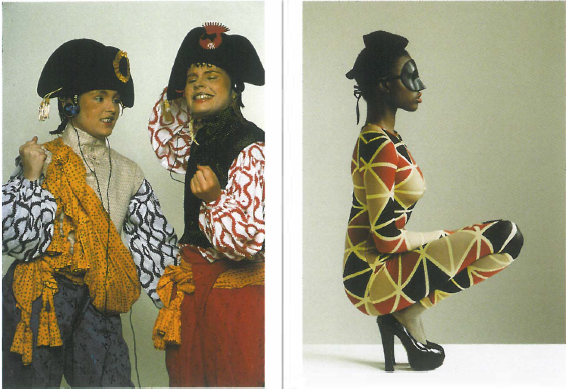

From Punk she went to pirates with massive over the top body decoration and wild colours. Nailing her colours to the Western tradition, this is the designer as Mannerist, adapting and distorting images and objects from history to make them more extreme than ever before. She celebrated the 18th century extravagance of the ancien régime in pre-revolutionary France with exquisitely cut cloth. Other clothes slash and bunch silks in extravagant emulations of layers of history.

It is in her admiration (and evocation) of the great traditions of English tailoring in fine tweed that Westwood shows both her Englishness and her inherently conservative bent. Tailored clothes can be adapted and experimented with – but only by the tailor. Creative dressing is limited to accessories. Westwood therefore is a designer always in total control as to how her clothes are worn. The photograph of a determined Nanny Whip Margaret Thatcher with the caption 'This woman was once a punk' could almost be an image of Westwood herself in its resolution and discipline.

The claim that Westwood was 'subverting the Establishment from within' is not consistent with her acceptance of an OBE or indeed the way the V&A created this exhibition. Instead it shows that once again the Establishment has invigorated itself by incorporating good red substance into its pallid bloodstream. In this sense the exhibition is indeed a celebration of the Routinization of Charisma, a crowning (in tweed) of the new face of the English sartorial establishment.